Ed: Special thanks to Maurice Clarett for allowing unfettered access into his life over the past month, despite grueling 14+ hour training camp days and a demanding family life.

August 24, 2002

We might as well start where the story of Maurice Clarett begins, as far as you know.

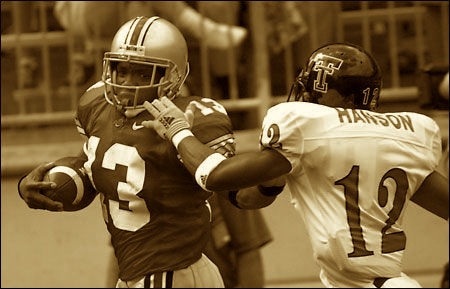

Ohio State is kicking off Jim Tressel’s second season at Ohio State. Texas Tech is the opponent.

Buckeye fans are certifiably crazy, but they’re not uninformed: Everyone in attendance is especially anxious to see one player who has never touched the ball in Ohio Stadium. They’re waiting, impatiently, for the freshman named Clarett to enter the game. He is the one wearing the #13 jersey.

Clarett arrived at Ohio State that spring and immediately generated attention with how he conducted himself. He wanted to win right away, and wasn’t shy about speaking his mind to his teammates or the media. He demanded that the older guys to try harder because he didn’t believe the Buckeyes were practicing well enough to win.

That's one way for a kid fresh from high school to introduce himself to a veteran team. The media reported his every word, and those words were appreciated by Buckeye stakeholders.

It is finally time for his first college game. Number 13 jogs onto the field for Ohio State's first offensive possession to the roar of approval from the crowd that had only discovered a few months earlier that the team would be hosting this additional home game against Texas Tech.

The Pigskin Classic is the 2002 Ohio State seniors’ second such preseason “classic.” They had lost the 1999 Kickoff Classic in decidedly un-classic fashion to the Miami Hurricanes in their first game as Buckeyes. In 2002 the Pigskin and Kickoff Classics would be held for the final time. Not so classic, as they turned out.

Regardless, Clarett is in the game, starting at tailback for Ohio State as a true freshman. The people are ready to be impressed. They are ready to see this kid walk the walk, too.

Tressel had told him prior to kickoff that he would get a couple of series before rotating with the other backs on the roster, which include Lydell Ross and Maurice Hall. When he arrived at Ohio State, Clarett was running with the last line. By the time fall camp ended, the freshman was running with the ones, and he now has no plans to ever run with the twos or threes again.

Clarett starts the game and helps move the team down the field, but Tressel substitutes Ross at the two-yard line and he scores the touchdown to end that drive.

On the second series, Tressel tells the freshman that if he doesn’t do anything special it's going to be his last series of the day.

On the second series OF HIS COLLEGE CAREER, Tressel TOLD CLARETT that if he DIDN'T do anything special it WOULD be his last series of the day.

Clarett promptly runs up the middle for one yard and is immediately pulled in favor for Hall, who runs for four yards on the next play. A couple of plays later Hall runs right into the offensive line for no gain. Clarett is subbed back into the game.

As he stands in the huddle, Tressel's edict echoes in his helmet. If you don’t do anything special, this will be your last series.

His energy is heightened. He lines up behind quarterback Craig Krenzel to run Ohio State’s bread and butter rushing play, known in the playbook as Dave.

The play begins. The left guard snaps backward and pulls right. Krenzel turns around quickly to hand the ball off and then all of a sudden – for the first time that afternoon – everything slows down dramatically. The freshman has the ball pressed against the right side of his ribcage and he can see everything developing in front of him, quite clearly. Almost immediately, the sounds of the stadium and the game recede. Everything is now quiet.

His blockers have created a big red wall for him to run around, so he runs around it.

Texas Tech is wearing white jerseys with white pants. The play is moving right with Clarett already past his big red wall, so he no longer sees any friendly jerseys. What he does see is a cluster of white and a whole lot of green grass. He runs directly toward the green. The white cluster fluidly slides left out of his frame of vision as he bursts past it. Now there is only green.

Clarett is chugging through the open green expanse, and in the distance he now also sees few thousand fans, all of whom appear to stand up in unison and start screaming. He still does not hear them; the only sounds bouncing around in his silver, sticker-less helmet are his instructions to himself: Run to the fans. Just get to the fans, man. Make them go crazy. Keep going, keep going, you know none of these guys can catch you.

Clarett reaches the fans in the southwest corner of Ohio Stadium for his first collegiate touchdown. All of the sounds of the game return, and the fans go absolutely crazy, just as he had intended. He doesn’t realize it at the time, but Tressel had excitedly run down the sideline after him during the play.

“I felt like I had arrived,” says Clarett, recalling that first touchdown. “I knew I was good, but that touchdown gave me confidence. Now that I had confidence, it was over: I was going to dominate and be contagious. I wanted my teammates to be as confident as I felt then.”

Clarett comes back in two drives later and along with Krenzel leads the Buckeyes to the one yard-line, where Ross again comes in and scores his second touchdown. For the second time, Clarett's heavy lifting produced a short Ross touchdown, giving him two scores on three yards.

The third quarter starts with Hall back in at tailback. He is a nice runner, but he is not the Maurice people wanted to see. Following a five-yard loss by the other Maurice, Clarett comes back into the game amid cheers. That’s the right Maurice.

The Buckeyes call the same Dave play that Clarett scored on in the first quarter from 59 yards out. This time Ohio State is on the Texas Tech 45 yard-line. Aside from the 14-yard difference, the play and the outcome are almost identical. Touchdown, Ohio State.

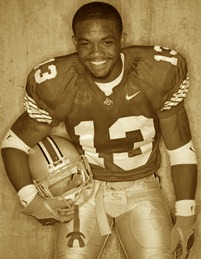

The stadium spontaneously begins chanting Mo-Reece! Mo-Reece! Mo-Reece! Mo-Reece! Over 100,000 people are joyously chanting his name. Some players dream of hearing their names being chanted by the crowd at some point in their careers; Clarett hasn't completed his first collegiate game yet and it is already happening.

The kid has arrived. There are hasty, unsophisticated discussions among his audience as how to celebrate this freshman who just showed up and took over at running back in a way not seen since Robert Smith had a decade earlier.

They realize the magnitude and importance of what they are witnessing. This is a future Heisman winner. This is young Archie Griffin ripping apart North Carolina in 1972 all over again.

Ideas are flowing through Block O. Maybe the students can throw Reese’s Peanut Butter cups onto the field? What words rhyme with Maurice? What rhymes with Clarett? Nothing rhymes with Clarett. Bassinet? No, that isn't going to work. What clever nickname can we give this kid? He’s only a freshman - he's going to be here for at least three more seasons.

As it turns out, the stadium should have been chanting, “REE-cie, REE-cie,” because that is what his friends have always called him. Nobody ever figures this out. To this day, Ree-cie has never been chanted in Ohio Stadium.

Twelve games from now against Michigan, with Ohio State averaging half a yard per play, a gimpy Clarett will come into the game and immediately rip off nine, then eight, and then 28 yards on successive plays calling his number.

On that last brilliant run, Clarett will pirouette through a miniscule hole in the line and burst outside around three Michigan defenders for a huge gain. Brent Musberger, who will be calling the game for ABC will excitedly blurt out, "the difference maker!"

It's not the exactly stuff that legendary nicknames are made of, but in light of how anemic the Buckeyes will look throughout 2002 when #13 is not on the field, Difference Maker is easily the most appropriate moniker Clarett will be given.

It is too soon for that reality to be evident against Texas Tech. The Buckeyes are comfortably leading the Red Raiders and Clarett stays on the sideline while the team plays ball control.

Two drives later, Clarett re-enters the game and plows into the end zone for the third time. Without the substitutions that had pulled him out of goal line situations twice earlier, it could have easily been the freshman’s fifth touchdown of the game.

It is an impossible debut for a freshman and a performance of pure fantasy for any veteran running back. He finishes his first college game averaging over eight yards per carry against a BCS opponent, and this is where the story of Maurice Clarett began, as far as you know.

August 24, 2011

It is nine years to the day from that remarkable debut against Texas Tech. Clarett is in terrific physical shape, and as one might have predicted back in 2002, in 2011 he is a professional football player...in Nebraska.

Omaha Nighthawks backfield, 2010

Omaha Nighthawks backfield, 2010

Clarett reported to the UFL’s Omaha Nighthawks training camp one day earlier than he was required to. He is up every day before 6am and he does not finish working until 10pm, long after his daughter has gone to sleep.

The Nighthawks are installing a new offense this season, which is further complicated by their current quarterback situation. Camp begins with four guys with very familiar names competing for just one spot.

With the rest of the offensive backfield, figuring out a new offense is usually more about mastering the timing than anything else. Omaha has only one receiver returning, which means the tailbacks could shoulder much of the burden offensively.

Clarett is boning up on his check downs and passing routes. He’s learning everyone else's position in addition to his own. Swing left, swing right; takedown left, takedown right. That playbook is hardwired into his brain. Camp just started. Nobody is going to know this playbook better than he does now.

When he arrived in Omaha last year, he was running with the threes, just as he was when he arrived in Columbus eight years earlier. Shaud Williams, who played at Alabama, ran with the twos. If you tally the total carries at the end of last season, Clarett actually touched the ball more. Williams and Clarett are entering the season as the two main guys.

He has never been personally closer to any other running back than he is to Williams, who is the best friend he’s had on any team he’s ever been on in his life. Clarett recently spoke at Williams’ Dream Big football camp in Texas. Their friendship is far bigger than their depth chart competition.

They bring two very different styles of rushing to the offense; Williams is a change-of-pace back who gets downhill quickly, while Clarett just prefers to run over people. They do have one thing in common: Both of them will gladly take the reps that no one else wants.

For college football fans, there are a lot of other familiar names on the roster.

“DJ Shockley (Georgia) is back to be our quarterback again,” says Clarett. “And we’ve also got (Nebraska Heisman winner) Eric Crouch, Daryll Clark (Penn State) and Jeremiah Masoli (Oregon/Ole Miss) too. I’m a veteran on this team. I came back stronger from last season.”

It’s the first time that Clarett has ever been a veteran on any football team since high school. It took the Omaha Nighthawks of the UFL and nine full years after his freshman debut at Ohio State to get to a point where he could be referred to as a "second-year tailback" on any team.

May 10, 1998

Clarett is in eighth grade, and he has just completed his third stint in juvenile detention. This time around it was for your run-of-the-mill B&E, which is a relatively tame malfeasance in his neighborhood.

In middle school Clarett gained a blasé attitude toward the severity of crime. What contributed to this attitude was that the only successful people he saw ever saw where he lived were the guys who were selling drugs. In that limited context, if crime was the only thing that paid, crime couldn't have been that bad.

USA Today Offensive POY, 2001

USA Today Offensive POY, 2001

One year from now he will be completing his freshman year at Harding High in Warren, OH. School is well over a half-hour drive each way from home, and his mother drives him both ways, which means she makes that trip four times every day. His father doesn’t take him to school or pick him up because, well, his father isn’t there. He hasn’t been there in ages.

In his mind, life can only get better from here. Clarett is fully aware of his surroundings, where he has come from, what he has endured and what can still be possible. He decides that he will wear #13, specifically because it is a number that symbolizes bad luck. You cannot choose what you’re born into, but you can navigate your own destiny.

He has been unlucky thus far, but he decides that period has ended. Now he’s in high school. Now he’s visible. There is no more limited context where only crime seems to pay. Now the future begins.

Clarett won't ever end up back in juvy again; apparently three times was the charm. Football helps him focus, and the fact that he is so dominant on the field helps keep him steady with his schoolwork.

It probably saves his life too. He ends up attending ten funerals of young friends before he even finishes up at Harding. He witnesses multiple murders as they happen; some in his neighborhood; one while sitting in front of his house.

He loses another friend to violence during the week of the 2003 Fiesta Bowl, when the team is already in Tempe preparing for the BCS Title Game. That is one funeral he cannot go back to Ohio to attend, and it isn’t because he doesn’t want to. He vents publicly. People who know very little about where he has been deem it to be a distraction.

The inconvenience of life occasionally causes people to miss funerals. It is a macabre statement, but 19-year old Clarett does not miss his friends' funerals. Of the many inconveniences he has encountered, none of them have kept him from paying respects, until now. That's nobody's concern right now except for Clarett's. Everyone else just wants him to focus on beating Miami.

The distraction of his football talent has helped a lot of people close to him mentally escape. They have known how good of a football player he is for years now, long before he wore a silver helmet. By the time the world outside of his own realizes how good of a football player he is at Harding, he is already projecting his potential to the college football players of the day.

“I loved watching Ricky Williams at Texas,” says Clarett. “He reminded me of a bigger me. Same with Shaun Alexander at Alabama and Earnest Graham at Florida. Ron Dayne was something else – he was just a different breed and I loved watching him play.”

He knew which backs he projected to, but he also knew where he wanted to play very early on: He liked Miami, but he also liked Ohio State.

“After having it rough for all those years, I just took (the recruiting process) all in,” says Clarett. “I enjoyed the moment. Whenever I went to any games on visits I just enjoyed the moment, and that’s the thing about recruiting: It’s overrated. The kid chooses the school. The kid decides. The kid thinks, ‘can my mother get to the game? Can my cousin, can my uncle?’ and that’s how I decided. The school didn’t choose me; I chose the school.”

As a senior at Harding, Clarett attends Tressel’s famous first game at Ann Arbor as a guest recruit of the University of Michigan. It is a game that Tressel had promised Ohio State fans they would be proud of 310 days earlier when he was introduced as the new football coach. He goes to the game with eventual Wolverine Prescott Burgess. They have been attending a lot of college games together.

“(Prescott) had some cousins – Alfie Burch, his brother had played up there and they were close with his family and pushing us to go to Michigan. A lot of guys were pushing us to go to Michigan. Most guys go on recruiting visits to enjoy themselves, not just to ‘go to the school they’re going to play for’."

“That Saturday I knew I was going to the Ohio State-Michigan game, as a guest of Michigan’s. That was all it was. I took it all in and enjoyed the moment, just like I did everywhere else.”

Clarett might have been seen visibly enjoying the Buckeyes rolling out to a 23-0 lead at Michigan, as a guest of home team’s. Not even three months later he is enrolled at Ohio State, majoring in Property Management. He had taken summer school classes prior to his senior year not to catch up, but to get ahead of schedule so that he could graduate from Harding early.

He participates in Ohio State spring ball and quickly earns the respect of the team. That respect gave him what he believes to be a mandate once fall camp began.

“I earned the right to call those guys out on the carpet,” says Clarett. “We absolutely had to be better than we were.”

Fourteen wins later, the Buckeyes are better than everybody else in the country. From the day he finishes his third stay in juvenile detention as an eighth grader with a checkered past and an uncertain future up until he stands on the victors' stage with his teammates in Tempe, Clarett operates his life on a trajectory barreling directly toward an NFL payday.

It is all but inevitable. This is what the top of the world looks like.

May 30, 2011

The coach who recruited Clarett to Ohio State back in 2001 has abruptly resigned under pressure from the university's Board of Trustees. An internal investigation found that Tressel had known of several players receiving improper benefits but that he failed to report the violations to the NCAA.

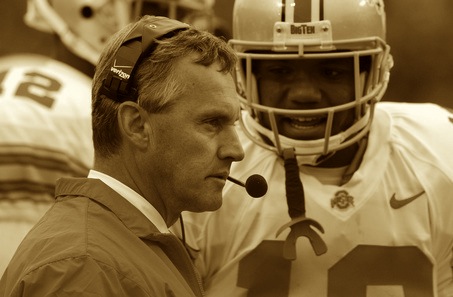

Tressel and Clarett on the sideline in Madison, 2002

Tressel and Clarett on the sideline in Madison, 2002

The ensuing scandal is the result of Tressel’s cover-up. The violations by his players – trading memorabilia and possessions in exchange for discounted tattoos – would not have produced a scandal of similar scale had they simply been reported when he discovered them.

This doesn’t prevent the public at large from playfully condemning “Tatgate” and openly discussing how far back this secondary black market memorabilia exchange has gone under Tressel, with his knowledge.

Anyone can go onto eBay or elsewhere to find a collegiate championship ring from time to time, usually after the fact by a player with exhausted eligibility who just needs the money. This common practice becomes a violation when the player still carries his amateur status.

Imagine signed jerseys, helmets, shoes – if you can name the article, it is already autographed and available for the price that the market dictates. The Tatgate scandal takes this widespread reality and repackages it, albeit falsely, as an Ohio State-specific problem.

One amateur who never traded his belongings for tattoos or cash is Clarett. His mother has his championship ring. It is in her house right now. All of his belongings and anything that could be considered to be unique memorabilia are in his possession. If he wore it, won it or earned it, he still has it.

No matter how bad it got, no matter how unseemly the bottom of the world looked and regardless of any desperation or straits he found himself in, he didn’t give his trophies, jerseys or rings away.

It’s not heroic, nor does he want or expect to be lauded for the "valiant" act of holding onto his belongings. He just refuses to part with them. He appreciated earning those things, likes having them and has always intended to keep them.

However, today Clarett is deeply affected by Tressel’s resignation. Despite the trouble he found himself in years ago, his coach at Ohio State never gave up or turned his back on him. He does not like the way Tressel has been treated and categorically rejects the notion that the virtuous image that he had crafted at Ohio State and through two published books is at all fraudulent. It’s a very sad day for Clarett, as it is for all Ohio State stakeholders.

As the details of the scandal continue to develop – some factually, some of pure fantasy – Clarett suddenly finds his name back in the news without having done anything improper to deserve it. Eight years after leaving Ohio State prematurely, that Maurice Clarett is on television once again, leaving school under inauspicious circumstances once again. It isn't happening again, though. This is just a rerun.

The names of Tressel’s football past, like Troy Smith, Clarett and Ray Isaac at Youngstown are brought back into the spotlight in an effort to reclassify several events of Tressel’s coaching career as the telling prelude to his downfall. Some people are buying this narrative, but Clarett is not one of them.

He finds it impossible that anyone could be a fraud for 30 years without being exposed very early on. He knows intimately how genuine and caring Tressel is, because he both experienced and rejected his guidance personally. It was not an act or deliberately conducted in public to serve as a message.

“He did not deserve this,” says Clarett. “To do what he’s done, it’s wrong for this man to just be thrown away.”

Tressel ultimately loses his job for behavior he committed when no one was watching. Ironically, many of his supporters, like Clarett, still champion his character despite what the scandal revealed - specifically for how Tressel behaved with them when no one was watching.

August 27, 2011

I have spoken to Clarett twice since he reported to Nighthawks training camp. We have also exchanged a whole bunch of text messages. The plan has been to collaborate on this story, but we’re not entirely sure what direction that story is going to take us in just yet. Right now the story is the furthest thing from my mind.

Hurricane Irene is steadily and painfully making its way up the Atlantic coast. My entire neighborhood in New Jersey has been without power for several hours. At 10:45pm, everything is dark, slightly warm and very, very loud, between the sound of the wind whipping tree branches into the roof and the rain hammering all sides of the house.

Every now and then there's a siren. Otherwise, the audible reminder of nature's occasional violence is unrelenting and inescapable.

Sleeping isn't really an option, so my wife and I are watching a movie called The Lincoln Lawyer on iPad and sacrificing battery power in exchange for temporary distraction from what is occurring all around us. The only light in the entire house is coming from the glow of the tablet.

And then another feint light suddenly appears: It is my cell phone on the table at the other end of the room. My wife walks over to get it, guided by the light it is producing and assuming it is someone just checking in to see how we were holding up in the storm. She arrives at the phone and picks it up, staring at the screen silently as hard rain continued to pelt the windows.

“Who is it?” I ask, figuring one of our friends was curious for information on how we’re doing.

She continues to look at the screen without speaking, as if she doesn’t believe what Caller ID is telling her.

“It’s, um…it’s Maurice Clarett.” She finally answers.

I take the phone from her to talk to him for awhile. After a week of getting to practice at 6am and getting back home way too late, he finally has a day off from football. He had spent time with his family and his daughter had gone to bed.

He is just calling to tell me to stay safe and that he is thinking of everyone being affected by Irene. Clarett is 1,200 miles away from the path of the hurricane, but the tension in his voice is genuine.

Nobody else will call that evening.

April 7, 2010

Toledo Correctional Institution normally houses around 1,500 inmates. Only a handful of them are subject to minimum or medium security.

The vast majority of its inhabitants are under close security, which is just one small step below maximum security. It costs taxpayers about $65 per inmate every day to keep the facility operational.

Visiting hours are extremely limited: You’ve got to arrive no earlier than 8:30am and the cutoff for entry is just 90 minutes later. The afternoon is a little more forgiving; where visitors are permitted from noon until 3pm. Reservations are required, and no more than two reservations can be made at once.

Prison is about isolation and rehabilitation, and the system for visitation contributes to that. At $65 a day times over 1,500 heads, the facility is required to produce rehabilitated citizens equipped to contribute to society, or its operations could be jeopardized.

For three and a half years, Clarett carries an inmate number here and spends his days and nights under close security. Today his early release request is being granted. For the next five years he will have to report to a community-based correction facility in Columbus.

Not long from now he will receive a judge’s permission to leave the state for 30 days to pursue a professional football career in Omaha. The hope is that he will make the team and be permitted to work and travel to road games as any other player would be. He’s leaving prison on a Wednesday. He’ll report to the team on a Saturday.

Back in 2002 he became the first freshman to lead a national championship team in rushing since Ahman Green did it for Nebraska in 1995. Coincidentally, Green is on the Omaha Nighthawks' roster. Upon hearing that his team is signing Maurice Clarett, he immediately volunteers to be his mentor.

The last time the public had laid eyes on him, he was haggard, overweight and in handcuffs. Over three years later, he’s noticeably lean, strong and smiling. Toledo Correctional is an unintended destination for anyone, but that does not preclude it from contributing to success stories.

"My physical condition is a credit to prison,” says Clarett. “When you are incarcerated, you have to take care of yourself all day, every day. You end up eating smaller portions. You read a lot. You work out a lot. You carry these habits every single day, and I was incarcerated for three years and four and a half months."

He pauses, as if to re-digest the fact that he has spent about an eighth of his life in jail.

"That was a lot of time to get healthy.”

January 2, 2006

Ohio State is playing in 35th edition of the Fiesta Bowl. It’s in the same stadium that Ohio State claimed the BCS title with Clarett, and it is one day short of three years since that night the Buckeyes upset the Hurricanes on that field.

It’s also a bowl game they won without his help again the following year, against Big XII champion Kansas State.

Today they’re playing the Notre Dame Fighting Irish, who are led by Brady Quinn, a quarterback and Dublin native that many Buckeye fans figured would be handing off to Clarett. Quinn could have ended up down the road from Dublin in Columbus, and Clarett was enamored enough with Irish assistant Urban Meyer that he strongly considered Notre Dame.

His senior year, Meyer left to take over at Bowling Green, so South Bend was no longer an option. As it turned out, neither Quinn or Clarett are with Ohio State today.

The Buckeyes roll up 617 yards of offense in beating the Irish 34-20. The game earns an impressive 12.9 Nielsen rating and garners interest from even casual college football fans, many of whom had just learned prior to kickoff that Clarett had been charged with aggravated robbery after being accused of holding up a couple outside of a bar and taking a cell phone.

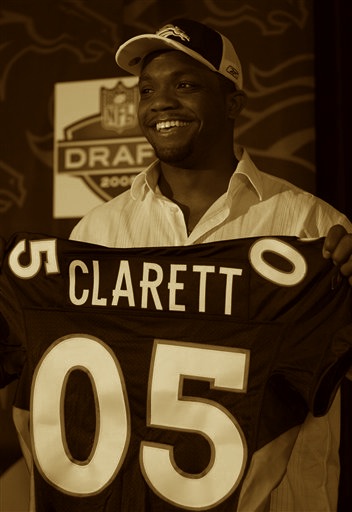

A few months earlier, despite an NFL combine workout that seen him run a sluggish 4.72 and then a 4.82 hand-timed 40 before eventually quitting the workout, the Denver Broncos still drafted him in the fourth round. Though he was able to get into better shape following the combine, he was unable to survive the squad's roster cuts and was out of football before the season began.

Eight months following this aggravated robbery charge, police will attempt to pull him over for what should be a routine traffic violation. After forcing a chase, police find Clarett in a bulletproof vest with an AK-47 loaded with 35 live rounds. There are also three pistols in the car, along with a bottle of vodka, a hatchet and curiously, a lint roller.

The judge gives him seven years in prison. He is 23 years old, and is being sent away for what amounts to his NFL years. This is what the bottom of the world looks like.

Assuming a four-year college career that was abruptly cut short, Clarett is off to prison just a few months following what should have been his final college game.

September 15, 2011

Clarett began writing while he was incarcerated. Today, while he earns a modest football paycheck, he is a regular contributor to OurBuckeyeHub, which is a comprehensive Ohio State resource for students, alumni and fans. Its users can blog, connect with lost and new friends, hire someone or find a job. Its purpose is user-dependent.

Clarett has chosen to use OurBuckeyeHub as a public confessional:

Percocet, Vicodin, codeine, Xanax, marijuana, alcohol. All of those substances have been a part of my life or my journey. Alcohol and drugs would go in and all of my insecurities, blessings, and thoughts would spill out.

Clarett minced defenses. He does not mince words, as he discards any subtlety about the chemical dependence that contributed to his downfall.

Michael Vick went to prison for years and successfully returned to his professional football career. But Vick was a Pro Bowler before he was incarcerated, and unlike Clarett his legal troubles did not overlap with any mental or physical debilitation.

Clarett dug himself a much bigger hole than Vick did. It’s going to be significantly harder to climb out of it, and he knows it. This is merely the self-inflicted version of what he was burdened with in his childhood, when he was unlucky and made his own luck. Once again, he is playing football. He is wearing #13, which is still a bad number.

I chose to feed my body with drugs and alcohol because I was weak and needed a place to hide. I’m a little stronger now. I’ve got my life back.

If you knew nothing about him and did a Google image search of “Maurice Clarett” you would get his story in snapshots: A big kid running around in a red #13 jersey, diving into the end zone to for the final score of the BCS title game, holding that Broncos jersey while smiling, looking defeated in a series of mug shots and courtroom photos, wearing beige prison scrubs, looking lean and determined in his Omaha Nighthawks practice shell.

The narrative is all there, without words or captions.

He also recently created a Twitter account, from which he sends out messages ranging from milquetoast philosophical quotations to biting insight on a number of issues. For members of the workforce long numb to the corporate ubiquity of motivational poster quotations, there is something compelling about seeing Clarett take to his life direction.

He is absolutely determined to succeed, without shortcuts. If anything, he's already given himself a series of extended detours. Clarett is so focused on the next chapter that he hasn’t watched Ohio State football yet this year (though he will get to see the Miami game in its entirety, unfortunately, in a couple of days).

He had to look up the Akron score on the Internet long after the game was over to see how it went. He knows there are big expectations for the Buckeyes, even in this turbulent year, even in every year. He expects a lot from the incoming freshmen, though nine years ago he delivered an almost impossible standard for them to uphold.

Luke Fickell, the Buckeyes' head coach as of right now, was Clarett’s very first position coach at Ohio State. When he arrived for spring ball in 2002, as a freshman his immediate destiny was special teams contributor. Fickell was coaching special teams.

He got to know his coach pretty well before he earned his way into the running back rotation en route to becoming the running back of choice. He is also quite familiar with Mike Vrabel, whom he met during the offseason when he, like so many other NFL Buckeyes, returned to Columbus to work out.

Tonight is Omaha’s season opener against the Virginia Destroyers. Clarett is going to see limited playing time and the Nighthawks are going to fall 23-13, but this is not the end of the plan. This is just part of it.

He lost touch with just about everyone he knew at Ohio State. He knows Troy Smith, whom the Nighthawks recently signed. Last week they cut the returning starter, Shockley, to make room for him. Clark, a fellow Youngstown native, is also no longer with the team.

Smith and Clarett were freshmen together in 2002 and both came to Columbus to escape somewhere far worse. At no point until now did their paths ever overlap; when Clarett was on top of the world, Smith was struggling. When Clarett was in prison, Smith was in New York City accepting the Heisman Trophy.

Clarett was the first member of Tressel’s first full recruiting class, while Smith was the last. Clarett was a must-have recruit with purposeful acquisition, and Smith was almost an afterthought who saw his first action with Ohio State as a kick returner, despite having been an Elite 11 quarterback.

Tonight they’re both Omaha Nighthawks, and tonight they’re spending most of the evening on the sideline, thinking, preparing and believing that this is a step toward something better.

Maybe he’ll get there, wherever there is. Clarett is at peace with himself, whether he gets back to the NFL or not. He refuses to deal in hypotheticals.

“I’m just happy right now,” says Clarett. “My house is clean. My girl is happy. My daughter is happy. I can’t think about an alternate reality where I stay at Ohio State or if I hadn’t gone to jail. I really don’t care about what could have been because that ship has sailed and it’s not coming back.”

And that’s Clarett’s reality: He was born unlucky, and he’s bounced back to make his own luck before. He’s doing it again, with a family and a healthier perspective than most people will ever have.

He will make his own luck once again, and he will have the life that he has always wanted. It might even include football.