Putting the ball in space for the sake of arithmetic.

Putting the ball in space for the sake of arithmetic.Upon their arrival at Ohio State, Urban Meyer and Tom Herman made clear that they wanted to force the opponent to defend the entire field, both vertically and horizontally.

"I think it's an offense based on using the entire width and length of the football field. The field is 120 yards long and 54 yards wide. And in our opinion the defense only has eleven human beings to cover that much grass, and so we're going to use space and numbers to our advantage."

One way spread-to-run teams have traditionally done this is with the bubble screen. (H/T: Smart Football).

The bubble is a way to get those favorable 'matchups' of 'speed in space' that commentators fondly discuss. But the bubble screen also serves a more specific strategic purpose--as a constraint against teams overplaying the base zone run.

As I have previously discussed, football is a game of arithmetic. The 'spread to run' helps an offense even the inherent arithmetic disadvantage by making the defense account for the quarterback as a run threat, allowing teams to run from the shotgun effectively. One way defenses attempt to 'cheat' in response to defend the zone is by sliding an an edge defender off the slot receiver into what Rich Rodriguez terms the 'gray area.' By bringing the highlighted defender closer to the box it assists in restoring the defense's numbers' advantage.

The bubble becomes an inexpensive check that constrains the defense from cheating. As Chris Brown states in discussing the 'constraint' theory of offense.

The idea is that you have certain plays that always work on the whiteboard against the defense you hope to see — the pass play that always works against Cover 3, the run play that works against the 4-3 under with out the linebackers cheating inside. Yes, it is what works on paper. But we don’t live in a perfect world: the “constraint” plays are designed to make sure you live in one that is as close as possible to the world you want, the world on the whiteboard.

Constraint plays thus work on defenders who cheat. For example, the safety might get tired of watching you break big runs up the middle, so he begins to cheat up. Now you call play-action and make him pay for his impatience. The outside linebackers cheat in for the same reason; to stop the run. Now you throw the bubble screen, run the bootleg passes to the flat, and make them pay for their impatience. Now the defensive ends begin rushing hard upfield; you trap, draw, and screen them to make them pay for getting out of position. If that defensive end played honest your tackle could block him; if he flies upfield he cannot. Constraint plays make them get back to basics. Once they get back to playing honest football, you go back to the whiteboard and beat them with your bread and butter.

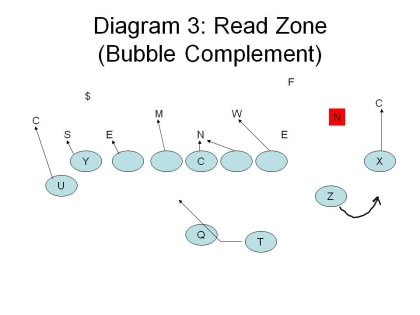

The bubble is therefore a a constraint upon a backside defender cheating against the zone read, which is itself a constraint upon the basic zone. We can thus work backwards and see how the spread-to-run offense developed. Teams wanted to find ways that they could establish an inside run game. But an offense must account for the backside defender, who is the quarterback's counterpart and thus unblocked. Coaches discovered that if they had the QB read that defender, suddenly that defender is constrained from crashing the front side run play, making it easier to run the base run play. If the defender continues to play the run, then the quarterback can simply pull and keep the football. In turn, a defense may respond by cheating their alley linebacker or nickel into the box. If that alley player can account for the quarterback, then the defensive end is again free to crash down upon the front side zone play. The bubble screen is a second level check upon the defense. It forces the defense to play straight up, providing the offense better numbers to run the base front side zone play. If the defense fails to do so, the QB simply turns and throws the bubble screen.

Even better, the zone read and bubble screen can be combined together into a package. In other words, the QB can either make an automatic pre-snap check to the bubble if the slot receive is uncovered, or he can throw the bubble during the play depending on his read. If the QB keeps the ball based on the defensive end crashing, he can make a quick run or throw read off the alley defender. The offensive linemen can run-block since the throw is behind the line of scrimmage. For example, as you can see in the diagrams from Florida's 2008 spring clinic, the half filled O's represent that the QB can throw the bubble screen on a given play depending upon how the defense reacts. The defense's job is thus made more difficult by the fact that they cannot 'guess.' The bubble screen thus serves the purpose of constraining the defense and evening out arithmetic, while having the added bonus of getting the ball to an athlete in space.