Three-star in-state linebacker CJ Sanna commits to Ohio State.

![[Waugh, pointing] "This is Brutus!" [Brutus, pointing] "That's your probation officer!"](http://www.elevenwarriors.com/sites/default/files/c/2012/05/pop_creeper.png)

When I was a child I got to meet Dave Winfield. Ditto Hayden Fry, Chris Mullin and a whole bunch of San Diego Chargers (thanks, Grandma).

My prevailing memories of those encounters are not so much wow, famous people but more geez these guys are huuuuuuuge. They're cool memories, but that's all they are - I've got no photos, autographs or mementos; just recollections of my tiny paw being engulfed by all of those giant hands.

For some people size doesn't matter. Celebrity does, and often times it matters a little too much.

When I was an editor at the Indiana Daily Student during undergrad we would joke about how star guard Damon Bailey had probably never worn the same pair of socks twice, because they would always find a way to disappear from his locker after he wore them once. I imagine those socks smelled...famous.

At a school-sanctioned autograph signing Bailey once came into contact with a grown man who proudly informed him that he had named his two children "Damon" and "Bailey." He even brought the boy and girl to meet their 19-year old namesake. Based on their ages it was evident they had been born during his legendary Indiana high school career.

If that seems appallingly young for an adult to embark on a mission of unhealthy hero worship, consider that football recruits Alex Anzalone, Joey Bosa and Mike Heurmann are current high school juniors, and after last week they're a little more famous than they'd probably prefer to be. Justin Bieber is older than they are.

It's likely adolescent girls at their respective high schools spend less time competing for their attention than 31-year old Charles Eric Waugh now-famously did, all with 16 years still remaining on his court-mandated 20-year term in the public registry for sex offenders, whose members are also forbidden from living within 1000 yards of a school.

Prior to being outed for his past transgressions, the creepiest thing about Waugh - aside from his overt stalking practices - had been that his facial expression and forced posture were identical in every photo he shared publicly. Now that he has since been arrested for violating the terms of his probation, his unsolicited involvement with Ohio State athletics should be permanently over.

To be fair to Waugh - and if there's a creepier feeling than giving a pedophile with a penchant for underage boys the benefit of the doubt, I don't ever want to experience it - his pedophilia and his predilection for Ohio State could be mutually exclusive. The problem for him is that they're legally not permitted to be.

At the same time it does the discussion around how creepy is too creepy a disservice, since outside of NAMBLA meetings there isn't a vocal opposition to keeping pedophiles away from children.

It's definitely possible to be shuddersome without having one's name on the sex offender registry (though being on that list definitely helps) but let's pretend he's just infatuated with Buckeye sports, since that dramatically widens the scope of people who can relate.

Not all fans come with creepy warning labels (yes, it's real)

Not all fans come with creepy warning labels (yes, it's real)How creepy is too creepy? Social media is many things to many people, including an enabling device for creepiness to everyone who chooses to participate. It's no different from an automobile potentially being both a mode of transport or a weapon: It all depends upon the operator.

Having an account on Twitter or Facebook, the two most-widely used platforms, isn't free of responsibility despite being free of charge. Fans desperately pander to be noticed by all degrees of celebrity on a daily basis, whether it's begging for attention from strangers or acknowledging tripe which developed brain stems should categorically ignore.

Unsolicited social media stalking carries all of the annoyances of telemarketing, but without a business model or a product. What separated Waugh from the horde of garden variety creepers and eventually outed him was a combination of red flags that he publicly waved for the world to see: He Tweet-spammed over 100 Ohio State recruits, players and coaches on a regular basis while pursuing photographs and meetings with several kids.

Normally this behavior would scream booster or agent. It was obvious Waugh was neither of these.

His "motivational quotes" went largely ignored, but some players and at least one administrator took the bait and acknowledged him. A handful of younger players even began following him back.

Fans and bloggers noticed Waugh's behavior, with the unnecessary clincher being his disturbing description of a photo containing his 31-year old self and three high school juniors barely half his age. Several people, including yours truly, notified OSU Compliance and suggested that the department keep an eye on him.

Less than 24 hours later the Lantern published its story and that particular threat, which the university classified as one to student/recruit welfare, was extinguished.

It seemed obvious that this was the right outcome, except that Anzalone rescinded his week-old commitment to Ohio State in the aftermath. This produced two unfortunate reactions: One, the story was seized upon with the same predictable vigor and attention that all Buckeye travails tend to receive (don't ever change, Bleacher Report) which peeled at the media scabs from last summer's sloppy free-cars-TV-ban-$40,000-handshakes "reporting" frenzy.

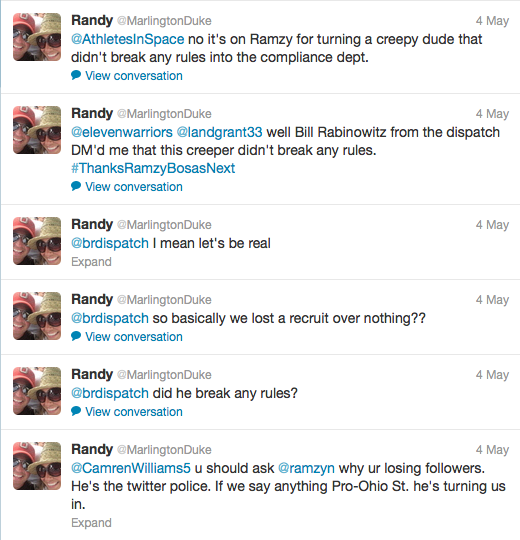

Second - for a few Buckeye fans - the hostility over what had transpired was not directed at Waugh but at those who dared to turn him in to OSU Compliance. Apparently it would have been more favorable to the football program to keep quiet about a possible predator on campus pursuing underage kids for fear of negative publicity. Why does that sound so familiar?

"But pedophiles stalking teens isn't an NCAA violation!"

"But pedophiles stalking teens isn't an NCAA violation!"At the same time, there were some scorned fans who were openly critical of Anzalone's family decision to decommit from Ohio State. I saw unsolicited tweets to links from the sex offender registry showing where registered offenders lived proximate to the Anzalones' home in Pennsylvania. I saw hostile reactions to a private family's personal decision from a fan base I'm a part of that made me hate myself by association.

I was asked - repeatedly - if specific acts on Twitter or Facebook were categorically considered creepy. I was given scenarios. I was asked for my unqualified opinion. PRO TIP: If actually you have to ask, it's probably creepy.

For the most part the entire episode was correctly viewed and digested as a non-Ohio State phenomenon. Over the weekend Penn State verbal Ross Douglas publicly came to Louisville-bound Kyle Bolin's defense when a creepy UK fan gave him unsolicited feedback regarding his college choice (click that link, or simply do a search on any recruit immediately after he eliminates Kentucky - it will blow your mind).

There's plenty of ugliness already in college football, from devastating injuries and widespread corruption to the facade of amateurism and the academic fraud committed by institutions to maintain a breadwinner.

Performance-enhancing drugs, runners and agents are not new, and neither are stalkers or invasion of privacy - on the Internet or otherwise: Schools have been warning and educating their athletes on social media best-practices since the platform was in its infancy (trivia: you know who stalks college athletes the most? The colleges themselves).

As fortunate as the outcome was - Anzalone's decommitment aside - unfortunately there was no real payoff or lesson learned: So there are dangerous, disquieting people in the world. We've always known this, both about the world and about college football, since the world's first fratricide. That wasn't exactly a mystery that the Waugh's emergence suddenly helped solve.

Creepergate, brief as it lasted, was beguiling because it combined the seedy elements that normally grapple people's attention anyway - and then added Ohio State football.

It was that final scarlet and gray variable that changed everything, and unfortunately spawned many creeps beyond the primary culprit. That's because adding that Ohio State variable, for some fans, somehow made Waugh's actions excusable.

For others, it made them more intolerable. And that shouldn't be possible. Ohio State football doesn't make stalking less acceptable. That crime stands on its own.