Past Shadows, Charles Csuri

Past Shadows, Charles CsuriThe Battle of the Bulge was fought for over a month in the winter of 1944-45, and was the last gasp of Hitler's dying regime. In a desperate effort to beat back the steadily advancing Allied assault in the western front, the Nazis threw almost everything they had left into a massive attack near the Ardennes forests in Belgium.

Close to a million men were involved in this campaign, and of those roughly 200,000 would be counted as casualties. Eventually the German forces were beaten back, thanks to an incredibly stubborn resistance put up by Allied troops (most famously by the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne), but the toll in both military and civilian life was massive: in addition to an unknown amount of Germans, roughly 19,000 members of the Allied forces and at least another 3,000 civilians met their end.

Of course, as devastating and brutal as the Battle of the Bulge was, it was mere child's play to what was going on in the eastern front. After Hitler's turn against Russia, breaking their non-aggression pact, the Soviets and the Nazis fought one grueling battle after another; at Stalingrad alone there were nearly a million deaths, and all told, roughly 30 million of World War II's 70 million dead came by way of the eastern front.

Former Ohio State football captain and 1942 national champion Charles Csuri was present at the Battle of the Bulge, where he received a Bronze Star for heroism during the fight. His story doesn't end there, however: he'd go on to become the father of digital animation and art, using computer technology as early as 1964. Now almost 90 and a professor emeritus at Ohio State, he still sometimes comes into the lab at ACCAD on campus and creates works of art.

So when Nike unveiled their Ohio State Pro Combat gear in the fall of 2010, complete with a bronze star on the back of the helmet, they thought they had found the perfect man to introduce it.

They thought wrong.

Csuri didn't explicitly attack the idea of Nike calling their marketing scheme "Pro Combat," but instead he essentially ignored it altogether. Instead of talking about the new fabric or stitching or how "breathable" it was, he gently reminded people that combat isn't exactly a word to be bandied around so easily. A Nike representative was then forced to come on stage and give all of the details himself.

It wasn't a big incident, but what's striking is the difference in attitude between a man who lived the terror of battle and the company that sought to exploit nostalgia to sell some jerseys. In Nike's promotional material they attempted to pump up the idea that they were honoring the championship class of '42, using battle sounds and pictures designed to evoke patriotic feelings about a horrific war that cost tens of millions of lives. They wanted us to relive the emotions that we feel when we see movies like the Dirty Dozen or Saving Private Ryan.

I don't think Csuri wanted any of that, and frankly, neither do I. Days like Memorial Day and Veteran's Day should remind us of the incredible sacrifices that men and women made and continue to make on a daily basis in service to their country. It should remind us that war is an awful exercise of death and suffering, and that the further we're distanced from it, the more likely we are to forget that.

Hated war enough to do anything to end it

Hated war enough to do anything to end itAfter 9/11, there was a thought that as a society we would stop using war terms and phrases to describe commonplace and mundane things in our society. Football games would no longer be "wars." A big loss would no longer be called a "slaughter." Quarterbacks were no longer "field generals."

Obviously that didn't last; as September 11th increasingly became a memory, those terms found their way back into our collective lexicon, even as the United States continued to fight two wars in which thousands continued to die. That doesn't make us unfeeling monsters or mean that someone isn't sympathetic to the costs of combat, but it does mean that as a country we're so incredibly removed from the pain and suffering of war that millions endure regularly, that we have the luxury of describing the relatively mundane in words that don't fit.

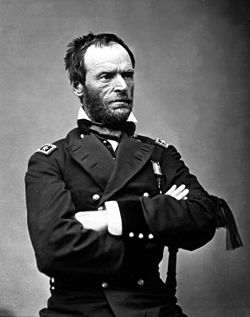

Ohioan and legendary Civil War general William T. Sherman had this to say about war:

"I confess, without shame, that I am sick and tired of fighting — its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentations of distant families, appealing to me for sons, husbands, and fathers ... it is only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated... that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation."

I hope that this Memorial Day you will remember the very real and ongoing burden that soldiers continue to bear which allows the rest of us to talk about war in such glib terms, a burden that most of us will never have to carry. And I also hope that you'll remember that sports aren't warfare; that as time expires and the last whistle is blown, all the bluster and violence and intensity of sport can fade away, and we can go back to being the people that we really are.

Because ultimately, that's the lesson here. As much as Nike and Under Armor and ESPN would love for you to believe, athletes are not soldiers and neither are fans. Soldiers aren't even soldiers. We're all people, and the most lucky of people who see combat aren't those who get canonized through a uniform or have a ship named after them, they're those who can come home and create something new and exciting, just as Charles Csuri did.