Andrew Sweat was living his dream. After a solid four-year career for Ohio State, Sweat signed a rookie contract with the Cleveland Browns, a team that plays less than three hours from his hometown of Washington, Pa.

Sweat never even put on the fabled brown and orange uniform, though. Instead, he abruptly retired from the game. Chronic injuries were never a major issue for Sweat – passing a physical wasn’t a concern. Sweat’s anxieties were much more serious in the sense of day-to-day living.

He retired because of concussions.

Decades ago, and just years ago, retiring because of a few bell-ringings would have been unprecented. Players would be largely mocked if a weakness was shown. Football was a sport of larger than life barbarians. Seemingly, nothing could keep them down for the count. And, surely, your man card would be revoked if you kowtowed to fears.

“We played real football back then,” former Ohio State running back Pete Johnson said, referring to the days of yesteryear. He played for the Buckeyes in the mid-1970s, when you were tackled to the ground on pavement so hard many believed it was concrete painted green.

Then large-scale cases of dementia, chronic headaches and even suicide began cropping up in former players. At first, the correlation wasn’t noticed. But as the rate of incidents rose, so did the suspicions. Former players from the 1950s, 60s and 70s – when technology and equipment was less than par – were thought to be the focal point of the issue. But players from the 80s, 90s and 2000s crept into the problem as well. Another contributor was the tough-man mystique – players would not stay on the sidelines if they could walk.

“I can remember getting led off the field by my teammates and not remembering it, then getting woken up with smelling salts under my nose, and 20 minutes later I’d be back in the game,” former Ohio State All-American linebacker Ike Kelley said about his NFL career with the Philadelphia Eagles. “Did that affect me? Some people would say, yeah, it has. I’m not going to say it’s overblown or underblown. I’d just say they haven’t done enough research to determine it. Anyone who just blows it off, that’s not factual. There is something to it. We just don’t know how much.”

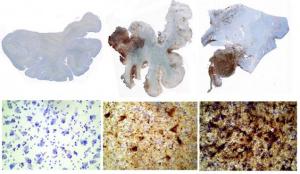

A healthy brain (left) conpared to one with CTE.

A healthy brain (left) conpared to one with CTE. Boston University began studying the deaths and determined that chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE for short, played a major part in former players’ dementia, headaches and suicides.

CTE is a progressive degenerative disease. It can only be diagnosed post-mortem. Because of this, former players have begun the act of donating their brains to the cause. Junior Seau’s family became the latest to join the study, donating the eight-time All-Pro’s brain after he committed suicide in May. CTE is found most commonly in people who experience concussions, including military service personnel. Individuals with CTE may experience dementia, aggressive behavior, confusion and depression. The symptoms can come in the short term or long term. While football has garnered the most attention, there are also concerns about other contact sports such as ice hockey, soccer and basketball.

An estimated 300,000 sports-related traumatic brain injuries, most of them concussions, occur annually in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

An American Journal of Sports Medicine study of the 1975-1982 college football seasons found that concussions were a persistent and regular but relatively infrequent type of injury. A primary reason goes back to the lack of knowledge on concussions during the time frame.

Concussions accounted for 75 percent of head injuries. The study determined that running backs were the most likely offensive position to suffer a concussion, while the secondary positions were the most at risk on defense.

"I didn't get concussions, I gave them," Johnson said.

"I didn't get concussions, I gave them," Johnson said.Sweat, a linebacker, suffered three concussions during his career at Ohio State, including one last season at Purdue. Following his concussion last season, Sweat experienced the tell-tale signs of repeated head trauma.

"I've never been depressed in my life,” said Sweat, who will pursue a law degree. “I'm the most positive person, and I was down. I knew it wasn't me. I couldn't control my thinking. I was not myself. My mind was not there. Some of the thoughts that were out there, I was getting worried about that."

While that experience gave him signals that something serious could be wrong, Sweat brushed it aside during the winter and spring, hired an agent and awaited his NFL future. Not until an accidental bang to the head the day before minicamp did Sweat walk away from his boyhood dream. As fate would have it, Sweat bumped his head in the shower – a Doomsday location for Cleveland – at the Browns’ team hotel. Symptoms he had experienced for months returned, and that’s when Sweat knew it was time to concentrate on something else.

“It scared me," Sweat said. "Football is not worth my health. It's really important to me that I'm able to have a family and a life after football. Football is a great game, but when you have a concussion like that, it's not worth it.”

More and more players, both past, present and future, are figuring that out. Another former Buckeye – Ross Homan – retired last season after suffering a concussion in the preseason, and several NFL players, including former Super Bowl MVP Kurt Warner, have said they wouldn’t let their sons play the very game that consumed their fathers’ lives and deepened their bank accounts.

Could we one day see this in Ohio Stadium?

Could we one day see this in Ohio Stadium?A lawsuit was brought forth against the NFL from more than a thousand former players, including former Ohio State Buckeye Dave Foley, accusing the NFL of hiding information that linked football-related head trauma to permanent brain injuries.

“The biggest problem I see is back then when the concussions were happening, the equipment wasn’t near as good and the coaching and medical staff really didn’t know how to deal with it,” said Foley, who’s had six operations for a detached retina in the past year. Doctors believe blows to the head led to the eye issue. “They’d ask you how you felt, you’d say I feel OK and they’d send you back in the game. I don’t know the long-range cause – I’m not a medical doctor – but I think it’s been proven that multiple head blows causes brain damage, and if you have brain damage you can do a lot of crazy things, like shoot yourself, and that’s a shame.”

More than a dozen former NFL players who have died in recent years have been diagnosed post-mortem with CTE. Several of those diagnosed committed suicide, including Dave Duerson, who took the step of shooting himself in the chest to preserve his brain. Before he killed himself, Duerson sent a message to family members telling them he wanted his brain donated to the CTE study.

“It bothers me when I hear about guys taking their own lives, Junior Seau being the most recent,” Kelley said. “He was a guy that seemingly had everything going for him. What I have found over the years is certain people can’t make the adjustment to the limelight of the NFL to regular life, so to speak. Did concussions cause that? I don’t know. But I know those guys have a lot of them, especially us guys who played linebacker.

“I think it affects different people in different ways. I have documented, from my days in high school through Ohio State through seven years in Philadelphia, 15 or so concussions. Some people say it’s bothering me, but I don’t seemingly have any cognitive problems. But I do not certain individuals act differently to certain injuries, and I don’t think concussions are any different. When you slam your brain against your skull it can be damaging. They still don’t know the long-term effects. I think the studies going on are good. The longer they go, the more they’re going to find out – yea or nay – on whether it affects everyone all the time.”

This week the Big Ten Conference and Ivy League announced they will co-sponsor a major research study on concussions and other head injuries among major athletes. The two academic heavyweights will combine resources to better understand the injuries from a physical and behavior standpoint, thus improving the well-being of athletes.

“Frankly, this is a unique moment in the history of science,” Dr. Dennis Molfese, Big Ten/CIC Research Collaboration Director and the University of Nebraska Director of the Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior, said. “There is no question that this research program will be greatly strengthened by bringing together in a genuine partnership the outstanding and cutting-edge scientists, athletic trainers and team physicians of both conferences to better understand and reduce as well as treat head injuries.”

Student-athletes who volunteer to be part of the study will be evaluated at different stages of their career – when they enter school, during their careers and after their careers. An assortment of medical personnel - sports medicine specialists, neurologists, neuropsychologists, neurosurgeons, biologists, epidemiologists and other experts – will lead the study.

Last season the Ivy League became the first conference in the country to limit the number of full-contact practices. Pop Warner, the largest football youth organization in the country, implemented rule changes just last week that will drastically reduce the amount of contact allowed during practice.

In 2010, Owen Thomas, a junior lineman for Penn, an Ivy League university, committed suicide. After his brain was studied, it was determined to contain the beginning stages of CTE. Thomas became the youngest person to ever be diagnosed with CTE. Though he never had any documented concussions, Thomas was known as a hard hitter, raising the possibility that he played through concussions and took multiple blows that led to sever head trauma.

Ohio State medical staff personnel closely monitor student-athletes who suffer head injuries. If an athlete is thought to be concussed, doctors will perform the various levels of concussion tests to correctly determine and diagnose the severity of the trauma. They will then be held out of contact until the symptoms have completely subsided, which is determined by passing a series of tests.

“I think concussions are a serious problem and have always been,” Ohio State athletics director Gene Smith told Eleven Warriors. “It is not an overblown issue.

“The most important thing is our team physicians have total authority with decision making on a concussion, not coaches. We have defined procedures to determine when a player can reengage.”

The NFL is a multibillion-dollar business, while college football is in the midst of playoff fueled discussions that could include a TV contract over $1 billion. When you have two business models that are clearly working, making changes to alter the product is rare. Yet, many believe that is exactly what will happen. Some already see football going over a bridge to nowhere.

“Did you watch the Pro Bowl this year,” Foley asked quizzically. “It wasn’t football, and it was a horrible display. I think there has to be some compliments within the rules to still allow the speed and violence but protects people’s heads.

“What really bothers me about it is I think the game itself will have to change in some ways. I hate to take the violence out of the game, but I think in the very near future there will need to be some drastic changes in the equipment or even the rules of the game. That’d probably be good for the everyone, including the game. If you have this game going on and it becomes worse and worse over time, eventually the public is not going to stand for it, either.”

Said Johnson, “You watch the NFL now and guys don’t even tape their hands. When was the last time you saw blood in the NFL? There used to be jerseys covered with blood when we played. I wish I hadn’t played hurt. I’d be walking a lot better.”

Johnson believes the research into concussions is much ado about nothing. In the years immediately prior to the discovery of CTE in former players, the main focus was on the brutality of knee, hip and shoulder injuries suffered in former players. Sports Illustrated even did a cover story on the decline of former stars, such as Johnny Unitas.

“I think it’s part of the NFL’s deal that overshadowed the real problem,” Johnson said. “I don’t know any guys who have dementia, can’t remember things or have headaches. But I know a lot of guys who can’t bend over and put a tee in the ground. Congress started investigating disability in the NFL and they came out with this dementia stuff. I just think it’s a cover and hard to prove. How can you prove it didn’t happen in high school or when you jumped off you bed? I think the real issue is guys who can’t walk.”

College football has already changed dramatically over the past 20 years. The sport went from the days of few bowl games to the Bowl Alliance and the dreaded Bowl Championship Series. The next 20 look like they could undergo even more change. Already, a four-team playoff is on the horizon.

Could Ohio State and Alabama one day square off in the national championship game in New Orleans with flags adorned to their hips? It’s doubtful at this point in time. But don’t rule it out.