Two time honored tactics: Overload and confusion

Two time honored tactics: Overload and confusionThe zone blitz is one of the most bandied about terms in football today but also one of the least explained. Today I want to examine where the zone blitz came from and the philosophy that underlines the concept. Next week I will look at the basic categories of zone blitzes.

Attacking Pass Protection

First, some background. The term zone blitz is colloquially used when a defensive linemen drops into coverage. But the term literally refers to when a team blitzes while playing zone coverage behind it.

Traditionally teams played man coverage behind a blitz, however, because bringing more than four defenders as rushers led to holes in seven deep zone coverage schemes. The zone blitz does not entirely correct this shortcoming, because often the zone behind the blitz contains less than a full compliment of defenders. The zone blitz instead arose from a desire to overload standard pass protection schemes.

One of the zone blitz's progenitor's was someone not often associated with innovation — Bob Davie. In the 1980s the run-and-shoot arose throughout college (and eventually) the NFL. The term "run and shoot" describes pass combinations, but it also employed a specific pass protection scheme. The quarterback would execute a half roll with the line doing sprint-out/turn back protection, and the running back blocking the end man on the line of scrimmage.

Teams could not blitz the run-and-shoot because the offense effectively constrained it. Periodically, the running back would block the defensive end for a long count, and then release for a screen. He would not be accounted for in man coverage because it was assumed he would block, thus leading to big plays. As Chris Brown describes, defenses were forced to respond:

It becomes a study in game theory and reading and reacting. So defenses responded to this tactic. They had to keep at least one safety or another defender back to spy the RB. Why does this mean no blitzing? If the RB is able to block the end man on the line of scrimmage while another player must sit back and not blitz, simply to see whether or not the RB releases on a screen. The net result was that R&S teams rarely, if ever, saw Cover 0 blitzing man defenses. They could always release four receivers, block with six (assuming their six could block the other teams' six) and not face any overload blitzes.

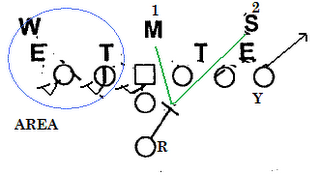

Davie's zone blitz effectively ended this condumdrum and the shoot's protection schme. From a 3-4 he would blitz the outside linebackers and drop his interior linebackers and linemen so that he could still play traditional zone behind it. The shoot protection could not handle it, as the running back had to stay in to block the blitzing linebacker while offensive linemen would be left blocking air. The offense faced an overload rush, but still had to deal with zone coverage so that it could not use hot reads.

The Zone Blitz's Rise in the NFL: Attacking the Dual Read

During this same time, NFL defensive coaches such as Dick LeBeau were looking for the same overload schemes to break down offensive pass protections.

Drop back pass protections traditionally take the form of area or man protection schemes (or some combination thereof). With only five offensive linemen, the offense generally uses a running back to have a "duel read" — he is responsible for the two linebackers to the side away from the protection. The theory is that linebackers are less likely to blitz, so the running back will be able to release if no blitzer presents himself, providing five offensive players as pass threats.

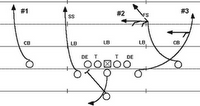

By overloading, the zone blitz throws this protection on its head. Look at the basic zone blitz below in comparison with the above pass protection.

Suddenly, the running back that is responsible for a dual read has both linebackers blitzing and cannot block both. Meanwhile, the offense is left with a guard or tackle to the opposite side that is left blocking air. The offense has to give up eligible receivers to block while simultaneously rendering a linemen without any responsibility. The defense, meanwhile, still has six defenders in zone pass protection covering the basic zones (generally in a three deep three under as shown above).

The zone blitz had the additional benefit of confusing a quarterback's blitz reads. Against a man blitz, when the quarterback saw the blitz he was told to throw hot away from the unblocked rusher. The zone blitz, however, puts a dropping defender right in that hot zone, potentially catching a quarterback unaware.

A Third Down Weapon

Even as offenses have grown accustomed to the zone blitz, however, the blitz remains particularly effective on third down. That's because it forces quick decisions. The overload blitz often leaves an unblocked defender, forcing the quarterback to get rid of the football quickly.

It's not all cake for the defense, however. The zone behind the blitz is not full proof. It generally includes only six--not seven--defenders as in traditional zone concepts. Further, the defense has a defensive linemen dropping that is unaccustomed to playing zone coverage. As such, the defense has underneath holes.

But the three deep coverage over the top is sound. And a quarterback that has to get rid of the football quickly against a scheme that has holes in the underneath coverage is generally going to throw it underneath. On third down and medium or long, a defense with three deep defenders facing the backfield can then come up and make a tackle short of the first down. That is why teams like Ohio State that are not blitz-heavy teams nonetheless often employ zone blitzes in these situations.

Next week I will examine some of the specific zone blitz concepts that teams employ.