Bob Knight's publicly cantankerous, irascible character conflicts with my own personal experience: He was never anything but complimentary to me. Granted, it was only one compliment.

I took Knight's basketball class my sophomore year at Indiana in 1992. He was technically the class instructor, but IU assistant Norm Ellenberger was there running the course most often.

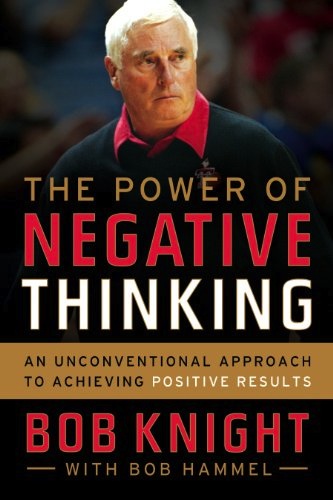

Knight's book comes out today. You can buy it here.

Knight's book comes out today. You can buy it here.Learning basketball from its high scholar was a unique and wonderful opportunity. Getting an A to counterbalance my pitiful grades in the economics classes taught by professors speaking English as their fourth language was just an added bonus.

Picture the prototypically lousy rec league player: Short, can't shoot, yet still kind of annoying on defense and constantly setting screens for better teammates, i.e. everyone else.

That was me. Actually, that still is me.

One day during a class scrimmage early on in the course, Knight stopped play to provide instruction. As he finished diagnosing what everyone was doing and how it could have been done better, he pointed at me and said the following:

You set screens better than Alan Henderson. Great job.

Knight had paid me the ultimate compliment, considering his strategy was built around the motion offense which heavily relies on screens to get shooters open looks at the basket. If anyone knew what a great screen looked like, it was that guy.

Screens were fine wine, The General was a renown sommelier and my vintage graded better than that of his star forward.

I couldn't wait to brag to my freshman year roommate James, who was Henderson's fraternity brother and close friend. Back when we lived together I'd regularly come home to find Henderson hanging out in our tiny space, which made him look even bigger and far more gangly than his 6'9 frame.

Over the balance of that fall semester, Ellenberger repeatedly complimented my screenery, my screen-fu and my expert knowledge of screenatology compared to that of Henderson. I ran around the court on offense, being trailed by the other team's worst player, and would find the right spot to free our guys for better looks.

And I'd hear about it whenever we scored. Nice screen. And then: High-fives, since fist-bumps hadn't been invented yet.

Over the following summer when I was back home in Columbus and taking classes at Ohio State, I'd mention the Indiana Hoosiers basketball staff's high opinion of my ability to stand in front of people during campus pickup games while I was busy scoring no points.

Knight and Ellenberger had found where I excelled and exploited it, rather than just telling me how bad I was at everything else. It was the ultimate positive reinforcement. Or so I thought.

That cantankerous, irascible character was never shy about telling his players just how bad they were, and the efficacy of his methods – 902 wins, three NCAA titles, 11 Big Ten championships and a gold medal coaching the 1984 men's basketball team – is revisited and showcased in The Power of Negative Thinking (New Harvest/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), which comes out today.

Knight borrows his concepts in negative thinking which have been studied and published already, albeit not through the lens of coaching college basketball. Even Oprah is already on board with the idea of exploiting negativity for gain. That central argument isn't as controversial as it may seem either, as negative thinking has been proven to show modest health benefits.

Nevertheless, Knight takes the position of contrarian in the "debate" in the negative-or-positive mindset. He was inspired to take his side after reading Norman Peale's The Power of Positive Thinking back when he was a student himself: Being cognizant of negatives is the path to positive results. Hope and wishful thinking are for the birds.

His stance was further solidified after being inundated with empty platitudes that provided little more than temporary diversions from stress or failure. Knight discovered that time does not heal all wounds. Healing requires a little more than just waiting.

IU freshman Alan Henderson. Not good at setting screens yet.

IU freshman Alan Henderson. Not good at setting screens yet.The title hints that the book is a study in coaching psychology and unlocking potential through unconventional means, and to a certain degree that's the story.

However, as the book progresses it becomes clear that Knight is also self-validating his methods by taking a selective look back at his Hall of Fame career.

His primary basketball exhibit in the case against platitudes and conventional thinking: The 1987 Final Four, when his Indiana Hoosiers faced UNLV and then Syracuse in the title game.

UNLV had Armon Gilliam, Freddie Banks, Jarvis Basnight and Mark Wade – they preferred to run teams off the court and score in bunches, while IU had a four-pass rule for every methodical possession. Knight decided to catch the Rebels off-guard and run with them. Final score: IU 97, UNLV 93.

The win came with consequences: The Hoosiers were physically drained from a style of play they were wholly unaccustomed to. So Knight canceled practice ahead of the title game with Syracuse so that his players could rest. That set the stage for his closing argument: Preparation over platitudes.

Knight cringes when he hears coaches and players talk about "who wants it more" since desire has a way of being upstaged by execution. He also rolls his eyes when TV analysts call for a timeout with seconds left so coaches can draw up a winning play.

Knight is fundamentally opposed to stopping the action to plan the last shot: That play should already be planned, practiced and perfected.

IU's winning basket against Syracuse – that Keith Smart baseline jumper that's shown every March – was set up by Joe Hillman, a reserve running the offense in the final seconds on account of his propensity to avoid mistakes (negative thinking); to Steve Alford, the precision shooter, who didn't shoot (unconventional planning); to Daryl Thomas, the post player, who passed on a contested inside shot (negative thinking, again); to Smart, who won the game leaping behind a Thomas screen.

It's a selective look back because he entirely ignores how his teams performed after 1994, when Indiana abruptly became an annual early-exit from the NCAA tournament. It also avoids shaming Derrick Coleman, who badly bricked two free throws prior to Smart's heroics.

The Power of Negative Thinking, or PONT [insert Tresselball joke here] plays out in attacks on what Knight refers to as good basketball's deal-breakers: Poor ball-handling, poor shot selection, poor transition play, weak free-throw shooting, failing to block out – which leads to poor rebounding – and playing uncoordinated defense.

He dwells on negativity and avoiding consequences because he believes that 1) tolerant people do not make good leaders, and 2) successful leadership means being hard to please. Reading between the lines, Knight is defending his methods which worked for most of his career. What he doesn't address is why or how he failed to win a conference title in his final 14 seasons of coaching.

If that seems like an unfair barometer for success, then blame Knight: He never went two seasons without at least finishing second in the Big Ten in his first 22 years in Bloomington, and every single one of those recruiting classes left school having won at least a conference championship.

Once players like Calbert Cheaney, Greg Graham and Damon Bailey left IU (he does not touch IU basketball that occurred after those players graduated, or Texas Tech basketball aside from saying everything except I absolutely hated Lubbock when describing its lack of basketball enthusiasm compared to Bloomington's) there are no further PONT success stories.

So what happened to Knight's teams on the back-end of his career? They were so emotionally spent by the time that March came around that they couldn't get out of the first weekend of the tournament. After his dismissal from IU, his assistant Mike Davis – more a positive-thinking recruiter and less of a game day coach – took Knight-trained players all the way to the NCAA title game.

However, once Davis gained responsibility for player development, he worked his way down from Indiana to UAB to now Texas Southern. Though his career trajectory has him eventually coaching high school basketball in Huntsville, it's hard to ignore the impact that his no-pressure approach had on Knight's schooled players, especially during March of 2002.

PONT borrows the Biblical directive of thou shalt not and applies it to basketball: Thou shalt not accept status quo; thou shalt not act without evidence; thou shalt not believe talent alone will determine the outcome (this could be a bumper sticker for IU in Knight's heyday) and thou shalt not talk too much.

The book is equal parts coaching philosophy, life lessons and personal memoirs, the last of which is sort of an embedded sequel to his 2002 book My Story. It has been said that history is written by winners, and a good deal of Knight's life lessons in winning are based in that history, ranging from Sun Tzu to the Battle of Gettysburg and every war in between and ever since.

Knight lauding his star pupil after surpassing his win total.

Knight lauding his star pupil after surpassing his win total.Also among those life lessons: Knight (an Ohio State guy) was hired by a Michigan Man™ (Bill Orwig) to coach Indiana basketball. It was as controversial at the time as you would expect it to be today, especially since Knight had indirectly landed his only college job at Army by volunteering for the Vietnam draft in order to possibly coach the Black Knights' freshman team.

So rather than hoping for the best, Knight planned and coached deliberately toward preventing the worst. While his philosophy didn't flow throughout his career at anything approaching peak efficacy, Knight entered the Hall of Fame 22 years ago and is only behind pupil Mike Krzyzewski and adversary Jim Boeheim in D-I career wins. It succeeded far more often than it failed.

Scattered between the philosophy, history and life lessons are some odd little sections entitled "Knight's Nuggets" in which he takes strawman positive-thinking (one more beer can't hurt) and expertly blows them up with PONT bombs (unless you're driving).

In the end, Knight and collaborator Bob Hammel have produced an uneven memoir that fails to acknowledge that motivation and winning are not necessarily a direct function of positive or negative thinking. PONT happens to be the perfect operational philosophy for me personally – but that's just me. Not everyone responds favorably to negative thinking.

Positive thinking can be just as efficacious provided its audience is wired to respond favorably to it. We're all snowflakes, Coach Knight. We're all different.

To that point: While he helped craft several college basketball legends, Knight also ran off numerous players. Either they failed him or he failed them, but it's clear that many of his transfers did not take to his methods, the same way that certain high school stars were never candidates to play for him – likely because they recognized this sooner than his transfers did.

I ran into James at the Indiana Memorial Union a week after receiving The Compliment. I told him to let Alan know that Woody (James' father's short-lived nickname for me, being his roommate from Columbus) was better at setting screens than he was, and that if he didn't believe it he could ask Coach Knight or Coach Ellenberger for confirmation.

Upon reading Knight's latest book, it's now apparent that I probably did not receive a compliment after all.

It was far more likely that I was unknowingly transformed into a delivery system for negativity that was intended for a student who could actually help Indiana win basketball games – and beat Michigan's Fab Five, whom Henderson's Hoosiers swept that season.

If that was the intent, the realization doesn't bother me one bit. I still haven't stopped setting screens for better players, and I probably never will.