A year ago this week ESPN's Wright Thompson gave me an advance screening of his 30 for 30 documentary Ghosts of Ole Miss.

Prior to seeing it I was only vaguely familiar with the story of James Meredith - Ole Miss' first black student - and the riots that accompanied his enrollment. President Kennedy sent the Army, Navy and National Guard into Oxford marking the first and only time since the Civil War that military action was ordered into the South.

That all went down in 1962, only about 600 miles from Ohio State - where its first black graduate Sherman Handlin had completed his degree 70 years earlier. Jessie Stevens, Ohio State's first black female grad finished her Bachelors in 1905, or 15 years before women in America were allowed to vote.

Call it historical ignorance, but it was fascinating to me that Ohio and Mississippi could be separated by so much more than just geography.

I wanted to learn more, so I boned up on Bill Willis, Ohio State's first black football player and member of the Buckeyes' first consensus national title team. He played 20 years before Meredith took on segregation at Ole Miss. Out of curiosity I also checked up on Penn State's black history since Ohio State was busy preparing for the Nittany Lions the same week I previewed Ghosts.

And that's when I first learned of Wally Triplett and the genesis of the ubiquitous We Are Penn State cheer.

That Penn State transition season of 2012 was marked by three conspicuous changes: The most conspicuous was Bill O'Brien replacing Joe Paterno after 46 years.

Paterno had absolved himself of any occupational coaching responsibilities for about a decade prior to his termination, so his literal absence had virtually no impact on the actual football being played. If anything, with O'Brien PSU gained a coach in headcount.

Nevertheless, the absence of Penn State's patriarch - who was routinely seen during his final seasons either asking assistants what was happening during games or dozing off while "coaching" from the box - was unnerving. Sixty-one years on one campus, however ignominious the exit, will do that.

The second change was the addition of names to football jerseys, ending the antiquated tradition of stripping individuality from the students generating billions of dollars for other people.

Highfalutin dead-enders stubbornly attached to the good ol' days were likely saddened by this recognition of the players who stuck with the university despite the NCAA's unprecedented and largely misguided punishment.

The third change, in part because of Paterno's refusal to retire gracefully, was the effort put into a visceral departure from one of the worst scandals in American history. There was no gentle or prepared transition period in State College. It was more of a wholesale reboot.

While Ole Miss had literally burned for days as the outside world watched in shock, Penn State secretly burned for years until the outside found out in horror. O'Brien and the vibrant community he chose to join worked diligently to quickly extinguish the shame and move on.

Those visceral reminders that Penn State's reputation wasn't constructed or destroyed in haste were visible from day one. The messages were pasted in Beaver Stadium, both before and after that week's game with the Buckeyes: We Still Are.

This is where Triplett's significance enters as a reminder that the real Penn State football culture was defined long before anyone had ever heard of Jerry Sandusky.

Thompson's Ghosts reminded me how much we still take for granted even 50 years after Meredith, as Ole Miss struggles to pry Colonel Reb from its heritage and Alabama's Greek system is still segregated. Washington's NFL team has retained its prominent ethnic slur nickname for 80 years. They're all defended as traditions.

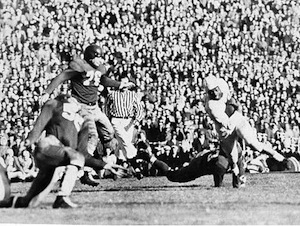

Triplett caught the game-tying pass in the 1948 Cotton Bowl.

Triplett caught the game-tying pass in the 1948 Cotton Bowl.

Triplett's family lived in a racially mixed neighborhood outside Philadelphia, which is to say he didn't live in either Harlem or Greenwich. Due to the confusion caused by his mailing address, he received a letter from the University of Miami offering him an athletic scholarship.

He answered the letter by politely informing them that he was black, since an offer from a Florida school that did not permit black and white athletes to play together indicated its administrators must have assumed he was white.

Miami responded with another letter apologizing for the mistake. There was no scholarship offer; not from Miami anyway. Triplett stayed in Pennsylvania to attend State College, and late in the 1945 season he became Penn State football's first black starter.

Ironically, the following season Penn State was scheduled to play Miami. The tradition at the time for the integrated team was to hold a meeting with the segregated team to decide what to do about the black players.

Most often, the school with black players would sit them against southern opponents, effectively supporting and endorsing segregation despite not permitting it at home.

Penn State was the first school to buck that trend in refusing to participate in a game with anything less than its entire roster. Triplett and Dennie Hoggard, the team's two black players, would not be left behind to satisfy Miami.

The game was canceled as a result of the team voting to play with all of its players or none at all. It was the final time Penn State would participate in one of those traditional meetings.

Two seasons later the Nittany Lions earned a Cotton Bowl invitation to play Southern Methodist, and word spread that SMU wanted to meet with PSU to discuss keeping its black players from traveling to Dallas.

Offensive guard Steve Suhey, the eventual MVP of that Cotton Bowl, then spoke his epitaph:

"We are Penn State. There will be no meetings."

That Cotton Bowl ended in a 13-13 tie and Triplett, whom SMU didn't want to see in Dallas, caught the game-tying touchdown in the third quarter. That We Are cheer was still in its crib, having just been born.

Yes, there is a lot we still take for granted, from Ole Miss slowly divorcing itself from its tragic past to Penn State quickly moving on from its own. Neither is easy or pleasant, but both are important and necessary to remember.

It's essential that non-Penn Staters understand and appreciate where We Are originated because fresh history has a way of clouding the older stuff. One monster and a few terrible, complicit people shouldn't be permitted to wreck a transformational legacy like Penn State's.

We Are is probably the most substantive cheer in college sports. More people should know its history, including fresh Penn Staters, because we take a lot for granted: Thompson embarked on his Ghosts project because even as a Mississippi native he never knew the full story. Remembering history like Penn State's is paramount to understanding that America has not fully emerged from darkness.

Their role in rejecting segregation - not just behind its own walls but daring to do so in the South - is too important to take for granted, especially as America continues to struggle in shedding some of its traditions. Think about that the next time you hear We Are Penn State; which will happen again this Saturday.

It isn't an empty cheer. It shouldn't be allowed to become one.