Well, that was an amazing game yesterday- at least, for us. I’d imagine it was less so for the Rutgers team. Still, it’s Sunday, which is a good day to relax, and consider some military history.

With our study of the 37th Infantry under our belt, let’s go back a bit. Well, perhaps a bit more than a bit. I’m not sure quite when I’ll end this particular series yet. I’ll see when it’s time.

As usual, if you found this topic interesting, please feel free to comment below. If you’re interested in previous works on military history here at Eleven Warriors, home to a surprising amount of good history for a sports site, please check out the archive by clicking here.

The End of Neo-Assyria

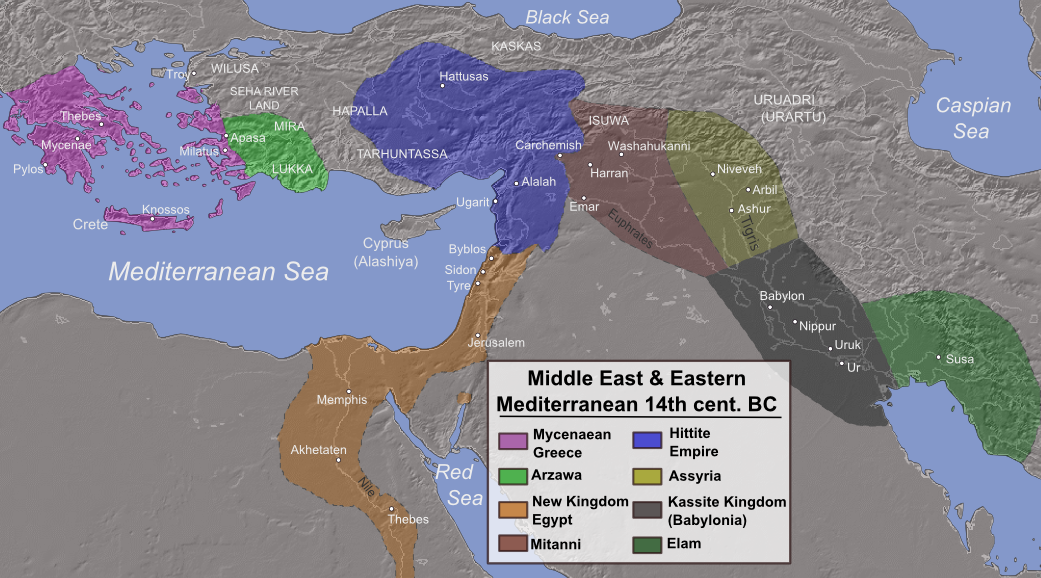

Life in 1300 BC in the eastern Mediterranean wasn’t too bad, considering. Sure, there wasn’t any electricity, or running water in every house, but, considering how bad life sucks for the vast majority of the human experience, 1300 BC is a pretty good time to live. Most people in the area lived under strong, well organized governments- Myceanea ruled much of what we called Greece, the Hittites ruled Asia Minor, the Assyrians and Babylonians split Mesopotamia between them, and the New Kingdom ruled Egypt. Cities dotted the landscape, trade moved across the seas, reaching as far as Britain and India, and literary lights and education, as far as we can tell, were widespread across the region.

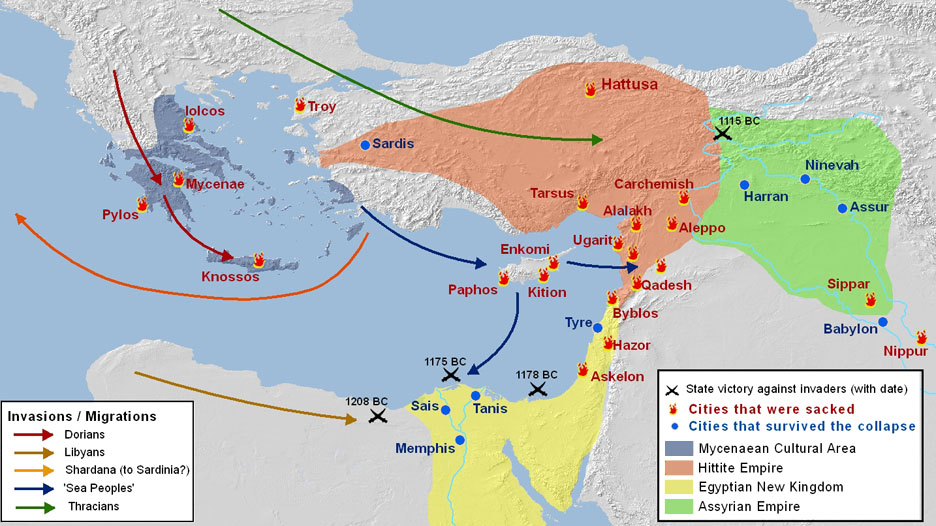

By 1100, this was all gone. The cities burned, most to lie in ruins forever. The people slaughtered, and replaced by migrating tribes. The languages gone, writing forgotten, and trade completely nonexistent. The governments collapsed early in the process. Why this apocalypse occurred, we’re really not sure. Theories abound, most of them related to changes in climate and the inability of these complex, intertwined societies to deal with disruptions in crops, trade and other factors. For the next few hundred years, people in the area lived in small kingdoms that came and went, few lasting more than a generation or three. War was constant, poverty rampant, and basics like food, water, shelter and trust in short supply.

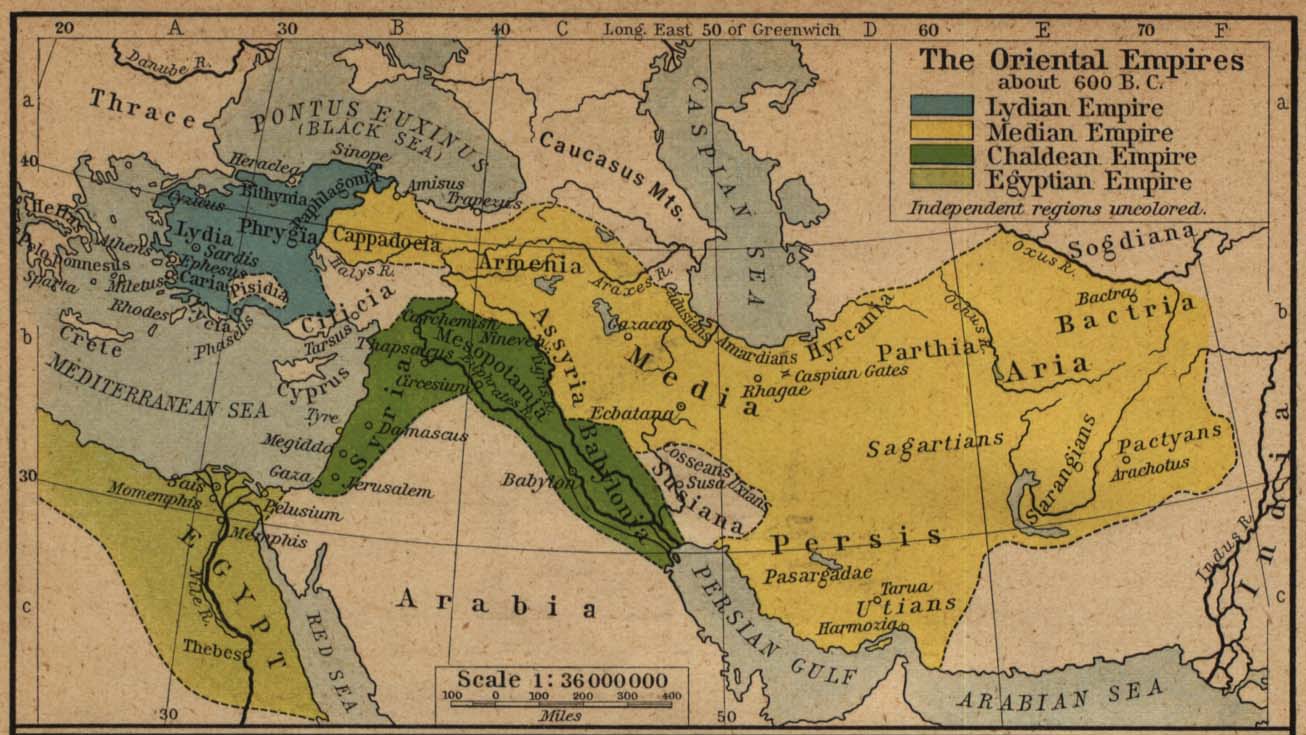

While many of these kingdoms were quite important in their own rights- the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah, the city states of Phoenicia, the Lydian and Phygian Kingdoms, and, of course, a new Kingdom of Egypt- we’ll talk about them as needed. Over time, these smaller kingdoms began consolidating into a number of larger ones. One of these kingdoms was a resurgent Assyrian Kingdom- the Kingdom of Assyria from the Bronze Age hadn’t been forgotten, and it’s name continued to ring out. A Middle Assyrian Empire rose in the 1000s, but collapsed fairly quickly. The Neo-Assyrian Empire reformed itself in the 900s, and expanded down the Fertile Crescent, only to stagnate and fight rebellions in their conquered lands for the next two centuries. However, in 744, Tiglath Plessier III took the throne, reformed the Empire, crushed Babylon, and expanded the boundaries of the Empire. In the late 700s, Sargon II conquered much of Asia Minor, forcing King Midas of Phyrgia to bend the knee. In the 600s, Esarhaddon and Ashurbainpal warred with Egypt, forcing tribute from the rich kingdom there.

The Assyrians were not, as a whole, nice people. They subjected their conquests and tributary states to ruinous taxes and tributes in an effort to extract the money needed to keep their army operating. This ended with constant rebellion amongst these tributary states, which, in turn, led to bloody reprisals and even more ruinous tributes. In general, the history of Neo-Assyria is an effort to repress rebellions long enough to conquer and sack new land, and to do so efficiently enough to keep the army together. In 627 BC, the death of Ashurbainpal led to a major succession crisis in Assyria. While claimants to the throne prepared for civil war, Babylon and Egypt revolted. The two kingdoms shook of the disjointed attempts to bring them back into the fold in the 620s, and then formed an alliance between themselves and the Medians in the east.. By 600, the three had subjected their conquers, founding the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Median Empire.

The Rise of the Persians

The Median Kingdom had come together about 700- just in time to get absorbed as a tributary state by the Assyrians. However, the highlands of the Zargos provided something of a barrier to attack, and allowed the Medians to survive and prepare for rebellion. After the collapse of the Assyrians, the Medians rushed into the void headlong, moving both to the east and west after 600. This rapid expansion brought them many vassal kingdoms, both from the old Assyrian Empire and from nearby tribes. Learning from the Assyrian example, the Medians didn’t rule with particular harshness, but tried to keep their vassals in line by intermarrying their royal families.

This arrangement lasted, more or less, until the reign of Astyages, who came to the throne in 585. While generally competent, Astyages believed a prophecy that his daughter, Mandane, would give birth to a son that would overthrow him. So, he sent Mandane to marry Cambyses, King of Asan. When she gave birth to Cyrus, Astyages eventually gave in to his fears and sent one of his men, Hapargus, to kill Cryus. However, Hapargus couldn’t bring himself to kill a princeling, so he took Cyrus, and gave him to a shepherd couple that had suffered a stillbirth- and took the stillborn baby to Astyages to claim as the dead Cyrus.

The charade lasted for 10 years, until Astyages found Cyrus. Rather than kill the boy, Astyages brought him into his court- and, reportedly, had Hapargus’ son killed and served to Hapargus at dinner, revealing that Hapargus dined on his son at the end of the meal. To get his revenge, Hapargus befriended Cyrus. When Cryus took the throne of Persia in 559, he urged rebellion. Cyrus didn’t attack immediately, but built up support and alliances for a rebellion, launching it in 553. Cyrus and Astyages fought it out for three years, with Cyrus getting the upper hand. Eventually, Astyages turned to Hapargus as the only general who could defeat Cyrus. Hapargus took command, and then he and the army muntied in 550, forcing Astyages to surrender. Cyrus took him prisoner, and kept him around his court until he died.

Cyrus moved quickly after the collapse of Median forces. He quickly assured the other vassals that he was in control, and settled their concerns. He shifted the alliance of marriages amongst his kings to reinforce loyalty to him, and refused to punish those who fought against him with Astyages. (Those who fought after the civil war against him did not fare nearly as well, of course.) Those members of Astyages’ family that he’d disenfranchised, he gave other lands to, which helped mollify them in the end.

The Battle of Thymbra

One person who was less than thrilled about Cyrus’ success was Croesus, King of Lydia. Croesus was the richest man in the Near East, with the Ionian Greeks, Phoenicians and Phrygians paying him tribute. He also allied with the Egyptians and Spartans, once he heard about Astyages’ capture. Asyage and Croesus were related by marriage, and Croesus figured he would eventually need to put his brother in law back on the throne. When Astyage died in 547, Croesus blamed Cyrus, and decided to go to war. He gathered up a great army of mercenaries with his great wealth, and attacked into Median Cappadocia. The two armies met in the winter of 547 outside the city of Ptreia, and fought to a bloody draw. As a result, Croesus no longer had the force to take the city while Cyrus lurked close by, so Croesus made a retreat back towards Sardis, his capital.

Croesus believed that, with winter upon them, Cyrus would give up the campaign until the spring. Once he moved back to Sardis, he began disbanding his mercenary forces, rather than pay them through the winter. However, Cyrus decided not to play by the rules, and instead marched his army through the hills and mountains of Asia Minor to Sardis, meeting up with Croesus near the town of Thymbra. With Cyrus in sight, and apparently willing to give battle, Croesus decided to oblige him.

The main reason that Croesus was willing to fight, despite disbanding his army, was that he still held a significant advantage in numbers. It’s not clear how many men were in each army (Centuries later, Xenophon gives 420,000 Lydians and 200,000 Persians, a more modern estimate gives 100,000 Lydians and 50,000 Persians, but either one of these is basically guesswork, hearsay and legend anyway), but the general agreement is that Croesus outnumbered Cyrus about two to one. He had large contingents of Egyptian and Babylonian troops, particularly Egyptian heavy infantry. While nominally mercenaries, many of these troops were given as support by the Pharaoh and Babylonian Emperors. The Lydians themselves were famous for their shock cavalry, using long lances. Together, these forces would make for a formidable attacking force- shock horse on the flanks, and reliable heavy infantry in the center. The heavy infantry would be supported by archers from Babylon.

The Persians were a bit more diverse of a force. They had some heavy infantry, notably the corps of 10,000 Immortals, but the real power of their infantry, and really, the bulk of the army, lay in archery. Archers provided much of the hitting power, with the goal of disrupting enemy formations before they got to the Persian infantry, opening them up to a counter attack. These archers were supplemented by largely light horse, throwing javelins and shooting bows. These forces could harass the enemy approach, then pursue the enemy when the archers put them into disorder. The mobile shock force of Cyrus’ army wasn’t in heavy cavalry, like Lydia, but in the hundreds of scythed chariots in the army. (The Lydians had chariots also, but didn’t really rely on them for much fighting power- more as mobile, skirmish archery platforms.)

Croesus anticipated a rather conventional battle, and deployed his forces accordingly. In order to counter the firepower of the Persian archers, he deployed his infantry in deep formations, so that even if the front ranks broke, the rear forces would be able to carry the attack forward. He put his cavalry out to the flanks, planning to break through the light Persian horse and sweep up the Persian flanks. Between his numbers advantage and the double envelopment, he figured he would carry the day.

Cyrus figured out that a conventional battle wouldn’t work out well for him, so he decided to employ a couple of tricks. The first lay in his formation. Rather than deploy in a line, Cyrus deployed in a horseshoe shape, with his flanks more or less refused. Points in this line were reinforced with siege towers, which would provide more firepower when needed. He then set up his chariots back off and behind this formation, to attack the flanks of the Lydians when they wrapped around the horseshoe formation.

He also had one more trick up his sleeve. Hypargus, ever the clever one, noticed during the campaign that Lydian horses were, for whatever reason, afraid of camels. On the march to Sardis, Cyrus created a corps of camel cavalry. He planned to use this camel cavalry to attack the Lydians on his left, and disrupt their attack there, while, on his right, he would drive around the enveloping wings of the Lydian cavalry, rolling them up from the flanks and rear.

The battle opened with an attack by the Lydians. Their horse move quickly to try and wrap around the Persian formation, which opened a gap between the Lydian horse and Lydian infantry. Into this gap, some Persian chariots attacked, driving off the Lydian chariots, and delaying the Lydian center. When the chariots dispersed, the Persian center attacked as well, moving forward to delay the Lydian center long enough for the Persian flank attacks to develop. As the Lydian cavalry closed to attack, Cyrus’ archers opened fire. In the dust and chaos of the battle on the flanks, the Lydians never noticed Cyrus’ reserve forces poised to attack them.

On the Persian left, the camels did the exact thing they were expected to do . They scared the Lydian horses, and pushed the forces back in disorder. To continue the attack, the Lydians dismounted and tried to fight on foot. However, heavy archery fire kept them from getting too organized, and their lances weren’t really designed for fighting on foot. They were still forming up when the chariots on the Persian right smashed into them, rolling through their ranks and breaking them. On the Persian right, Cyrus led his personal guards into the flanks and rear of the Lydians, rolling them up over the course of the battle and driving them back. Eventually, the Lydians, surrounded, crumpled, broke and fled. Meanwhile, in the center, the Egyptians pushed the Persian infantry back, but fire from the siege towers checked them for the moment, leaving them vulnerable when the cavalry peeled off.

Cyrus managed to keep control of his cavalry and chariots, and, rather than having them pursue a broken enemy cavalry, he pulled them back to the flanks and rear of the Egyptians. Seeing themselves surrounded, the Egyptians formed up into a refused block, and began to give a good fight of themselves. Both they Egyptian commander and Cyrus feared that the other would be able to wipe them out, and so the two met in a parley. Cyrus allowed the Egyptians to leave the field intact and under arms, so long as they went back to Egypt. The Egyptians agreed, with the stipulation that Egypt would remain neutral, rather than be called upon to fight the Lydians. This agreement worked out for both sides, and the Egyptians headed home.

Casualties in the battle were quite high, but that’s all we know. We don’t know how many men fought, and so we don’t really know how many died. However, the Persians were in good enough shape to march on Sardis itself, and, after two weeks, took the city. Croesus fell into the hands of Cyrus, who ordered that Croesus and his family be burned to death. However, when Croesus mounted the funeral pyre, a vast rainstorm came up, which doused all the fires and prevented the pyre from lighting, Believing that the gods to whom Croesus had prayed had saved him, Cyrus decided against killing him. However, Croesus died the next year anyway.

The fall of Sardis placed great wealth in Cyrus’ hands. Croesus was the wealthiest man in history up to that time, and his mercenary bill had barely dented his fortune. He also took control of the Ionian Greek cities, many of which were quite wealthy themselves, and provided a great deal of tax revenue, as well as access to Mediterranean trade. The wealth, men and trade made the Persian Empire under Cyrus quite powerful, but not the only power in the region- the Neo-Babylonian Empire still ruled Mesopotamia, while the Egyptians were still a formidable, organized force in the Nile valley. Cyrus wasn’t finished yet.