While many of the 11W faithful are well aware of the struggles that plagued That Team Up North, no on-field issue may have been more publicized than the play of the Wolverines’ offensive line in 2013. While finishing the season 7-6, Brady Hoke’s squad featured 5 different starting lineups in those 13 games, with only two mainstays in tackles Taylor Lewan and Michael Schofield. To fill the gaps inside, Hoke turned to a collection of highly touted underclassmen, including former blue-chip recruits such as Kyle Kalis, Erik Magnuson, and Kyle Bosch.

After finishing the season ranked 115th in the nation in yards per rushing attempt, Hoke made drastic changes to his coaching staff in preparation for the upcoming 2014 campaign. However, with the loss of Lewan and Schofield to the NFL, there is still a great deal of concern up north about this unit’s ability to improve moving forward.

Conversely, Ohio State featured one of the program’s finest offensive lines of all time in 2013, finishing fifth in the nation in rushing yards, and tops among all teams in FBS in yards per carry. The gap between the two units was so wide, that the Buckeyes averaged over twice as many yards every time they ran the football (6.8) as the Wolverines (3.28). Yet with the departure of 4 senior linemen, some fans in Columbus have begun to worry that the young men in Scarlet and Gray may endure struggles similar to that of their rivals.

The common response to those fans (on the internet, at least) has often been along the lines of “Trust Coach [insert Meyer, Herman, or Warriner],” and at the risk of sounding like a common fan, I agree for the most part. The offense that has been established since the arrival of this coaching staff is nearly the polar opposite of the one that former play-caller Al Borges ran the past three years in Ann Arbor. Borges’ offense more resembled the 2013 Buckeye Defense in a philosophical sense, lacking a clear identity and often struggling to consistently execute the plays that were called (which we’ve discussed at great lengths).

When reviewing the film of last year’s gang from Ann Arbor, the absolute first thing that stands out is the massive amount of formations. I truly feel bad for the opposing grad assistants and video coordinators that had to chart all the different combinations of personnel and alignment while scouting the Maize and Blue.

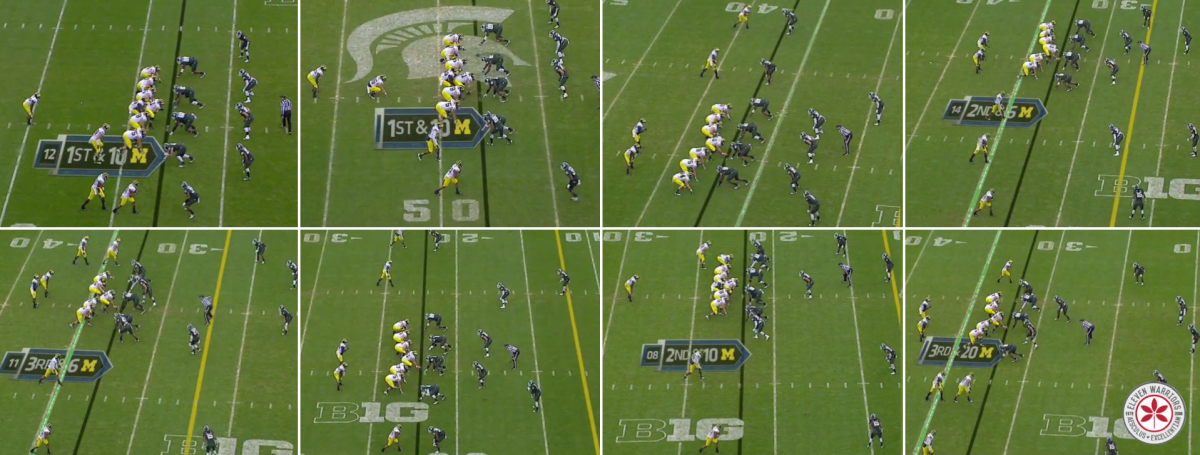

I will refrain from breaking down each and every formation they ran, to save us all time (but mostly my sanity), but an example can be found in the opening drive of the Michigan State game:

On this eight-play drive, Borges called eight different formations, featuring a mix of one-back, I-formation, shotgun, double TE, and 4-WR looks. Having called plays since 1986, Borges has likely seen every personnel combination imaginable. Unfortunately, he was coaching 18-22 year olds that have only seen a fraction of what he has on the football field.

Granted, offensive linemen rarely ever line up in different spots, so the alignment of the backs and receivers shouldn’t be an issue for them. However, the NCAA only allows a limited amount of time each week for teams to practice together, and the first step to running a play is lining up. Add in the consistent lineup changes, and it’s no wonder that the Wolverine offensive line often looked like they were running plays in a game for the first time.

I must admit, the number of concepts that Borges, Gardner, and co. tried to execute last fall was actually quite impressive. The Maize and Blue dipped into every trend seen in major college football over the past decade, ranging from empty backfield sets with Air Raid passing concepts, to option runs from the pistol, and Jumbo sets with multiple TEs and overloaded linemen to run the ball. Heck, they ran at least 4 different versions of the throwback screen alone, by my count.

Chip Kelly spoke about this very subject in 2009, as his Oregon offense was taking the college football world by storm:

"If you give your players something to hang their hats on, they will perform. If they can run the offense with any scenario they may face, you will be successful in running the ball. If they have all the answers to the problems the defense may give them, they will be good.

"The best way to beat the team you are going to play is to have your team play with conviction. Are there any basketball coaches in here? The one thing I cannot understand about their sport occurs in the clutch stages of the game. With the game tied and five seconds left in the game, the coach calls a time-out. He picks up a whiteboard and draws a play. I do not know how long I would last in Eugene, Oregon if I did that.

"If your players have not run that play in a critical situation over a thousand times in practice, you will not have a chance to be successful. With our inside zone play, we get so much practice time and so many reps that we can handle all the other scenarios that come about. Instead of trying to outscheme your opponent, put your players in an environment where they can be successful because they understand exactly what they have to do."

This series against Nebraska was a perfect example of the grab-bag approach to offense that Michigan often relied upon:

-

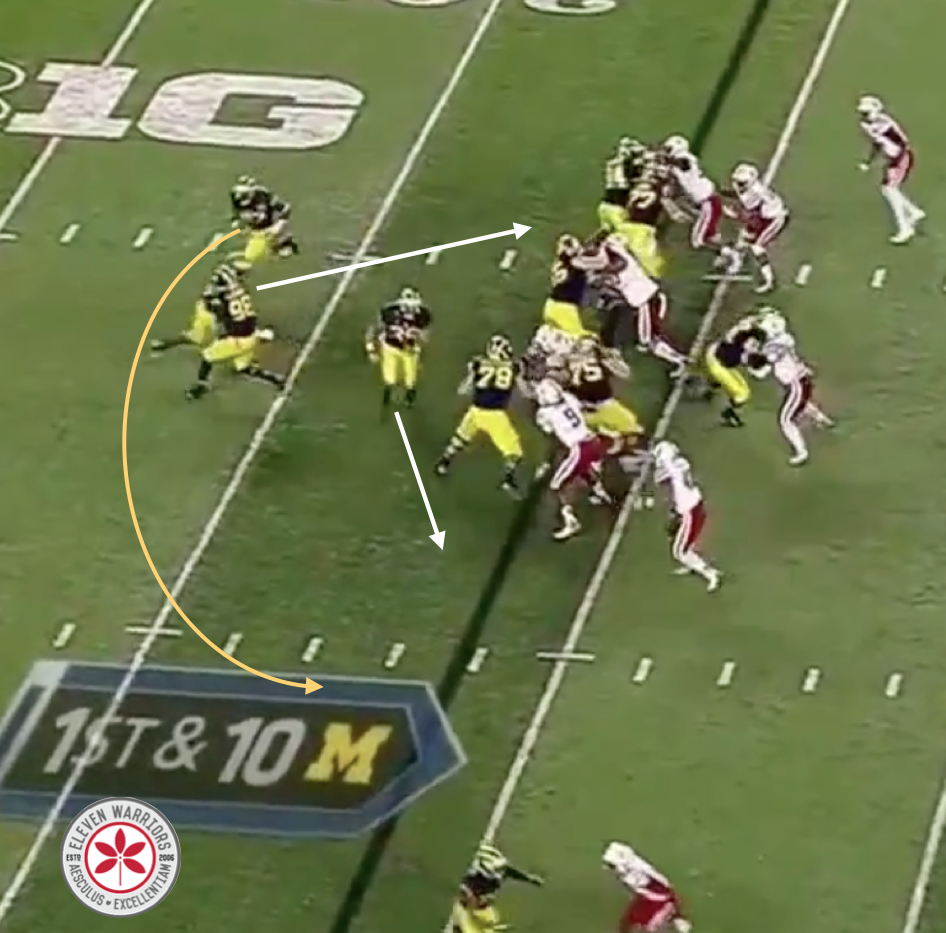

First Down: As the defense sat back and tried to read yet another formation and motion, an End-Around designed to get the ball to playmakers Devin Funchess netted 5 yards:

-

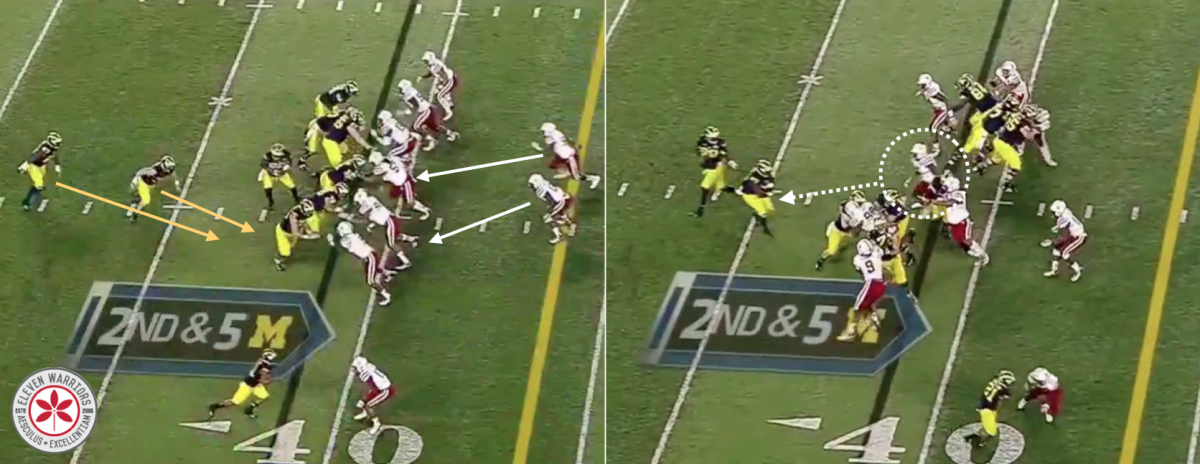

Second Down: Inside lead zone from the I formation, a formation from which the Wolverines rarely ever threw the ball. The Nebraska defense immediately crashed down in run support, creating more defenders than Wolverines to block them, and the middle linebacker darts into the backfield untouched to make an easy tackle:

-

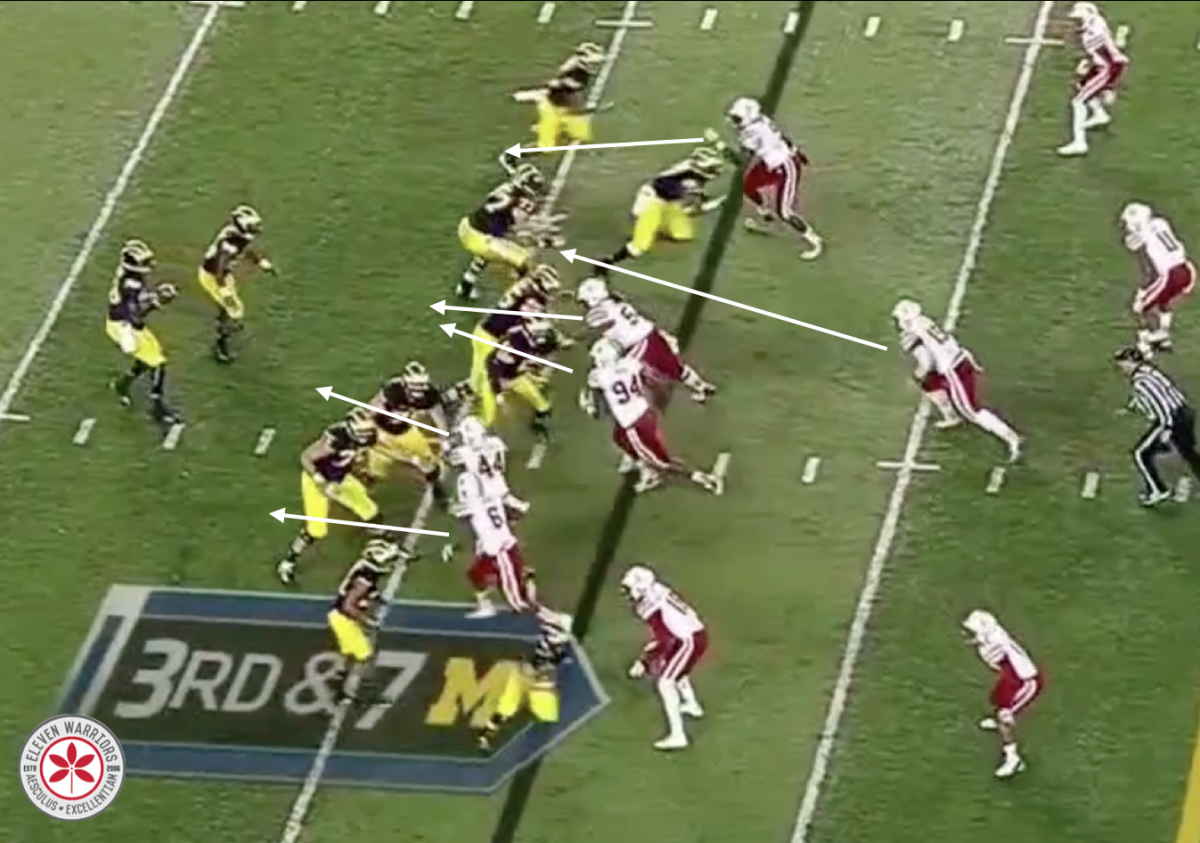

Third Down: Now in an obvious passing situation, the Cornhuskers bring the blitz. With only two down linemen, the defense was obviously trying to confuse a young defense that they had been attacking all game. Brady Hoke’s crew had enough bodies to account for all the blitzing defenders, but the delayed blitz was poorly picked up by running back Fitzgerald Touissant (a consistent issue for the Maize and Blue in 2013). The blitzing middle linebacker pressured Gardner enough to force a rushed throw with little chance of completion:

On the surface, the series appeared to be a “woulda-shoulda-coulda” scenario for fans of the Wolverines, just missing out on a first down. But the literal gains from the first play wouldn’t lead to much more, both on that series, and later in the game. The formation from which the Funchess run appeared didn’t return for the rest of the game, with the end-around acting as a constraint play to open up the handoff inside that was initially faked.

Quarterback Devin Gardner and crew were somewhat effective on first and second down, using their plethora of formations and concepts to keep defenses off balance. But on third downs, without the threat of even a minimal running game, defenses attacked the Maize and Blue offensive line with an array of blitzes, and stunts.

While I’m sure the readers of 11W would love a weekly series simply highlighting poor play in Ann Arbor, there are takeaways that can hopefully be applied to the development of the young offensive linemen in Columbus.

The first, and most important of which, goes back to the quote from Chip Kelly,

"With our inside zone play, we get so much practice time and so many reps that we can handle all the other scenarios that come about. Instead of trying to outscheme your opponent, put your players in an environment where they can be successful because they understand exactly what they have to do."

One of the questions that I posed in advance of the Spring Game was if the offense would begin to work in more schemes, such as outside zone. While the Buckeye offenses seemed more focused on developing the passing game during that game, it was clear that the Inside Zone play is still the foundation upon which the entire offense is built.

Much as was shown in the comeback in Evanston versus Northwestern last October, the goal of the Buckeye offense under Meyer, Herman, and Warinner is to keep the defense from committing to the inside zone run by forcing them to respect the pass.

By not only running deep, play-action passes that appear at first like inside zone, but also by packaging the run play with a quick pass, the defense has no choice but to play on their heels.

This is not to say that the inside zone is the perfect football play, and that all Hoke and new OC Doug Nussmeier need do is run that concept all the way to a championship. However, IF a team is going to commit to that, or any scheme, nothing can replace the value of a line running it over and over, together.

Unlike the game of chess, both sides are moving at once on a football field, meaning all the arrows drawn above are subject to change through the course of a second. Being prepared to adjust as needed, and more importantly, know how the guy next to you will adjust, is paramount to the success of an offensive line.

As we head into the 2014 season, the key to the success of the Buckeye offense is not only identifying the 5 best offensive linemen on the team, but ensuring they’ve spent enough time to build trust in each other’s ability. Otherwise, as many of our friends in Ann Arbor can attest, Autumn Saturdays may become a very trying time for all of us.