A young Ohio State team outperformed nearly all expectations in its long-anticipated road matchup with Michigan State. The Buckeyes combined masterful offensive game planning and execution with timely defensive stops en route to a convincing victory.

In so doing, Ohio State received career performances from numerous players. But none more than their redshirt freshman quarterback JT Barrett -- who answered any questions about how he would perform against a top 10 defense.

Painting a Picasso

Urban Meyer and offensive coordinator Tom Herman's unveiled a superb game plan that effectively responded to, and took advantage of weaknesses in Michigan State defensive coordinator Pat Narduzzi's 4-3 over, cover 4 defense.

Herman and Meyer began by stretching the Spartans' defensive backs horizontally. Cover 4 is equivalent to a matchup zone in basketball. But when two receivers to one side release vertically, it becomes man coverage. The corner and safety are responsible for the number one and two receivers, respectively.

Cover 4 requires a lot from defensive backs -- both in pattern reading and coverage skills. As discussed, the Michigan State defense has been susceptible this season to allowing explosive plays, owing to an inexperienced field corner and boundary safety.

Because those defensive backs had to defend vertical routes with man coverage, they had to provide sufficient cushion to the Ohio State wide receivers -- particularly Devin Smith. So Herman and Meyer exploited these Spartans defenders in executing their cover 4 principles by attacking underneath that cushion with vertical stem routes. On the first drive Herman solely dialed up passes -- namely hitch routes off play-action and packaged plays that were open underneath the retreating corners.

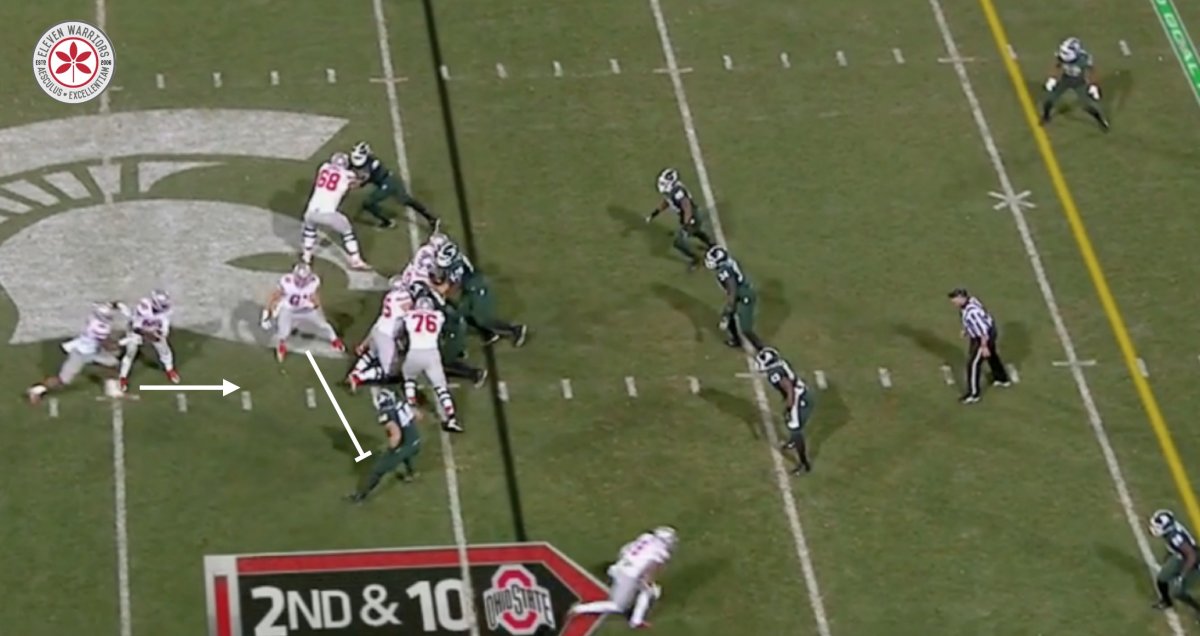

Herman next turned to the inside run game. As with previous opponents, Michigan State was particularly focused upon the Buckeyes' tight zone read play. So Herman used the play sparingly and turned to the counter tackle wrap or dart play, using the Spartans linebackers' aggressiveness against them.

For the rest of the contest, Herman mixed runs with horizontal throws. Just as they responded to Michigan State's cover 4, the Buckeye coaching staff had a plan to address Narduzzi's front seven in both run and pass blocking -- namely gap blocking.

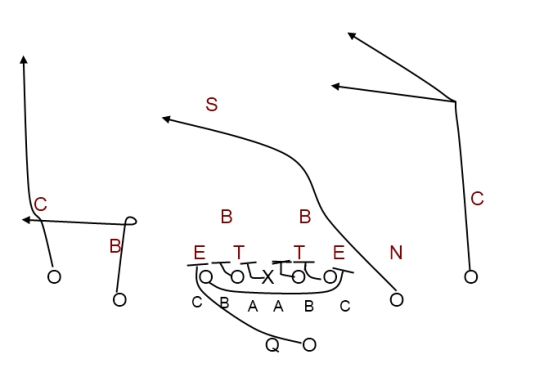

One favored tactic of Narduzzi is a double A-gap linebacker blitz. Such a play could have been effective against the Ohio State tight zone run game that aims for the A-gaps. And the Buckeye offensive line struggled earlier this season with blitz recognition and protection.

Gap blocking alleviated both problems. With gap blocking, every front side lineman blocks down to their inside gap while a backside guard, tackle, or tight end pulls and kicks out, leaving every blocker responsible for one gap. (H/T: Smart Football).

Against Michigan State, by only having to account for a single gap the offensive line's need for blitz recognition was reduced. It allowed the Buckeyes to readily account for every gap and block whoever may appear, particularly from the inside out. And it created angles to make things easier.

This applied to both the run and the pass. As noted, with the run game, the Buckeyes largely eschewed its base tight zone read play and relied heavily upon gap blocking. The extensive use of tackle wrap is one such example. So was the Buckeyes' repeated use of power and QB counter trey. These plays, along with lead quarterback outside zone, had the added benefit of getting Ohio State outside any potential Michigan State inside linebacker blitz to the C and D gaps, where they could conflict the safeties who have force responsibilities.

Likewise, the Buckeye passing game relied heavily upon a play-action gap scheme.

As with the run game, either the backside guard (often Pat Elflein) or tight end would block across the formation. Or if the tight end was aligned on the line of scrimmage the protection would slide to the open side. After carrying out his fake, the tailback was responsible for picking up any edge blitzer away from the pulling blocker.

In action:

Not only did six and seven man protections ensure that every gap was covered against Narduzzi's blitz-heavy scheme, but play action is most effective with a pulling guard, as the run fakes helped hold the Michigan State safeties. And between half-rolls and sprint out passing, Herman altered Barrett's launch point and limited Barrett's reads, allowing Barrett to establish a rhythm.

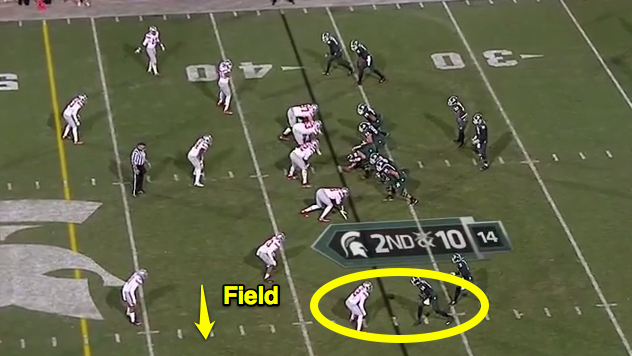

Once Herman and Meyer stretched the Spartan defense horizontally, they took their shot to Smith. With Narduzzi's quarters scheme, the aggressive safety play will provide several deep opportunities. Michigan State's boundary safeties have been vulnerable to getting caught up in underneath action and allowing receivers behind them.

As Kyle discussed, Meyer and Herman schemed to put Smith against that safety by bumping him into the slot. The play-action fake flat footed the deep defender, allowing Smith to accelerate by him. Barrett made a perfect throw and Smith ran to the football.

Effective Efficiency

As critical to the Buckeyes' offensive output was its short-yardage and goal line success. Ohio State has struggled at times in short yardage this season, as opponents have schemed to take away the Buckeyes' up-tempo, tight zone run.

But against Penn State the Buckeyes solved this issue by running quarterback split zone from an empty backfield. The Buckeyes continued utilizing quarterback split zone against Michigan State -- with great success. With split zone, the offensive line blocks tight zone. The tight end blocks back against the weak side defensive end, creating a natural cutback lane.

After several successful attempts the entire stadium knew the play was coming. But the Buckeyes repeatedly converted through spreading the field, controlling the defensive interior -- and through superb short-yardage running from Barrett, who is effective in short yardage because he runs north and south and keeps his legs churning.

As a result, the Buckeyes had 100% percent efficiency in converting short yardage and goal line opportunities -- resulting in a significant difference in offensive output compared to Penn State.

Bringing your A-Game

Short yardage running was but one aspect of Barrett's outstanding performance. Questions remained about how Barrett would perform against Michigan State, given his struggles against the two top-10 defenses he faced in Virginia Tech and the Nittany Lions.

Barrett quickly answered any questions. He was decisive in his progressions and threw in rhythm. He trusted his blockers with blitz pick-up and stepped up in the pocket. And when he throws with timing he delivers an accurate, catchable ball.

And Barrett was equally successful as a runner. His effectiveness comes from his skillful economy of movement. When he commits to run he plants his foot, makes one cut, and runs north and south. He is a big, strong runner, and his commitment to getting upfield both leads to him eating up yards and makes him effective in short-yardage. So although he is not the flashiest runner, he consistently produces explosive plays in the run game.

The Buckeyes' also received significant contributions from their most critical skill players. Ezekiel Elliot played the best game of his young career. Throughout this season Elliot has gained significant yardage after contact.

But he had very few explosive plays. Because he was running with so much forward lean, he was missing potential cutbacks and getting tripped up in the secondary.

That changed Saturday. Elliot ran more upright, and used stellar vision and acceleration to accumulate four runs over 15 yards.

Perhaps even more importantly, Elliot is already one of the best pass blocking running backs in football. Time and again Elliot would come across the formation in the Buckeyes' slide protection and pick up the blitz, allowing Barrett to step up to deliver the football. The difference from Penn State was, on Saturday, Barrett trusted his protection would handle the Michigan State pass rush.

And Barrett received critical help from his two primary receivers -- Michael Thomas and Devin Smith. In contrast to last season, where the Buckeye wide receivers failed to beat Michigan State's press coverage, on Saturday Ohio State wide receivers won at the line of scrimmage and gained yards after the catch.

Smith in particular controlled the game in the first half. The Spartans could not both play their base cover 4 and defend Smith. Field corner Darien Hicks had to provide Smith sufficient cushion, allowing Smith to catch easy hitch routes early. And he then still beat the Michigan State defensive backs vertically. In the last two weeks, Smith has played more physically, aggressively going up and catching the football with his hands,.

But no group deserves more praise than the Ohio State offensive line. As Meyer stated post-game, left guard Billy Price -- who has been the most inconsistent in pass protection -- was once beaten up front early.

But such problems were otherwise non-existent. The biggest improvements have come from the interior offensive line. Center Jacoby Boren, Elflein, and Price controlled the line of scrimmage -- particularly in short yardage -- and eliminated any inside pass rush. All three graded a champion, with Boren receiving his second consecutive player of the game award. The improvement of players such as Boren has been nothing short of meteoric and offensive line coach Ed Warriner deserves serious consideration for offensive assistant of the year.

Punch and Counterpunch

On defense, coordinator Chris Ash modified the cover-4 looks he uses for spread offenses to defend the more pro-style Spartans. As is his wont, Ash utilized more single high, cover-1 robber looks.

The biggest adjustment was with his corners. Doran Grant normally aligns to the boundary, with Eli Apple the field corner. But on Saturday, Ash had Grant follow Spartan wide receiver Tony Lippett around the field.

Despite the Ohio State changes, Michigan State was able to periodically move the football through several wrinkles. Apple was limited by a hamstring injury and did not start. On the first drive the Spartans took advantage of his replacement Gareon Conley, beating Conley over the top and to the flat for the game's first score. On the next drive Apple quickly returned.

The Spartans also took steps to combat the Buckeye defensive line. Michigan State generally chipped or doubled Joey Bosa.

Michigan State then used the Buckeyes' defensive tackles' aggressiveness against them. Michael Bennett in particular was able to get penetration. So the Spartans influenced Bennett up-field and trapped him.

In so doing, the Spartans created run lanes by creating separation between the defensive line coming upfield and the linebackers. Michigan State succeeded running the football because the Buckeye inside linebackers remain somewhat slow in their reads and coming downhill. The Ohio State tackling was also sub-par compared to previous weeks.

And Michigan State's 14 play, second quarter touchdown drive was made possible by utilizing quarterback Connor Cook in the run game to pick up critical third downs.

Making Plays When Need Be

Although far from perfect, the Buckeye defense kept an explosive Spartans offense in check for critical stretches -- particularly in the second and third quarters while Ohio State built its lead.

Several players were critical to this effort. Despite Michigan State's efforts to block him, Bennett made several crucial tackles for loss. But no play was more important than Grant. He was excellent in coverage, preventing Lippett from creating any explosive plays, which has been the Spartans' primary method to score points.

As a result, Ohio State forced Michigan State to drive the length of the field. And in doing so, the Buckeyes rendered Cook and the Spartans' passing game sufficiently insufficient to stop several drives.

Michigan State did score two fourth quarter touchdowns with relative ease once the Buckeyes went up by three scores. This resulted from a combination of playing softer zone coverages, an inability to get to Cook, Conley's return in place of Apple, and some questionable calls on the Spartans' last touchdown drive. Although frustrating, the goal was to force Michigan State to use clock driving the length of the field.

So while not perfect, the fourth quarter should not negatively color an otherwise solid effort. And the defensive performance would have looked far better if they converted any of the potential turnovers that were there for the taking.

X's and O's -- and Jimmy and Joes

Although Meyer and Herman deserve credit for an stellar game plan it was not significantly different than their plan for Michigan State last season. The difference was that last season the passing game -- from blitz protection, to throwing, to wide receiver separation -- was inconsistent against a stronger Spartans' defense. When you are throwing on first down, the difference between completing the throw and getting to second and three, and having an incompletion leading to second and ten, is enormous.

On Saturday the Buckeyes executed to near-perfection. From hitch routes, to bubble screens, to the run game, the Buckeyes ran those plays with timing and precision. To lose the turnover battle 2-0, not significantly flip field position (perhaps outside of a Jalin Marshall punt return) and yet score 49 points against a top five defense was one of the better offensive performances in recent memory.

The Buckeyes must now quickly move past that win to prepare for a road game against a solid Minnesota team. In particular, the run defense will have an opportunity for improvement against David Cobb and the Golden Gophers' ground game.