The Buckeyes have had a long and storied tradition of producing successful running backs whose skills translated well to the professional level. Although none were selected in this past weekend's draft, eleven backs (including two fullbacks) have heard their names followed by "Ohio State" called from the commissioner's podium over the past twenty years.

Some of these players, such as Eddie George, Maurice Clarett, Beanie Wells, or most recently, Carlos Hyde, were selected for a bruising running style desired by many NFL teams. Guys like Michael Wiley and Boom Herron were chosen thanks to their all-around abilities as football players, expected to contribute to the team in any number of ways even if they never became 1,000 yard rushers.

Outside of special teams, running backs are typically expected to contribute to their team in one of three ways: running, blocking, or receiving. Draft experts love to talk about each aspect when projecting a back's success at the next level. So it may seem odd then, that of all those backs selected, few were ever asked to catch the football while wearing the scarlet and gray.

In 2014 though, that changed. Ezekiel Elliott became a household name for his efforts over the back half of the year, becoming the workhorse for an offense that couldn't be stopped in the first college football playoff. But he also became a valued part of the passing game, logging more receptions in one year than any back since George's 1995 Heisman-winning campaign in which he tallied 47.

Much of the production (or lack thereof) from the backfield can be attributed to the offensive systems that were in place. During George's time, the Buckeyes were a classic I-formation team with a number of west-coast offense influences, meaning the backs were often released to the flats in an effort to stretch the defense horizontally in the passing game.

But after coordinator Walt Harris left to become the head coach at Pitt in 1997, John Cooper relied more heavily on one-back offensive principles that utilized more multiple-receiver sets when throwing, asking the backs to spend more time in pass protection. That trend would remain during the Jim Tressel era, as OSU runners were rarely asked to catch the football, even early on in his tenure when the I-formation was still heavily called upon.

Even after Urban Meyer began installing his 'power spread' system in 2012, the trend had still yet to change...until Virginia Tech effectively upended his entire scheme in last September's home opener. While their 'Bear' front not only jammed up an inside running game, the man coverage they employed on the outside caused problems through the air.

| Player | Season | Receptions | Rec Yds |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Carlos Hyde |

2012 |

8 |

51 |

|

Carlos Hyde |

2013 |

16 |

147 |

|

Ezekiel Elliott |

2014 |

28 |

220 |

But as is the case with ANY defense, there were holes in the coverage. The Hokies decided the areas they'd leave unguarded were deep and over the top as they played without a free safety, but also outside in the flats. Virginia Tech knew that the Buckeyes rarely looked to this area in the passing game, and effectively called Meyer's bluff, leaving it wide open all night long. With a young offense led by a young QB, Meyer was never able to exploit the weakness.

That changed almost overnight, however. In the following week's matchup with Kent State, the Buckeyes regularly attacked the flats through the air, setting a framework that would be repeated over and over in game plans that followed. The idea is a simple one, build extensions of the running game into the passing game, allowing playmakers like Elliott and Curtis Samuel to get the ball in space, stretching the defense to cover the entire width of the field.

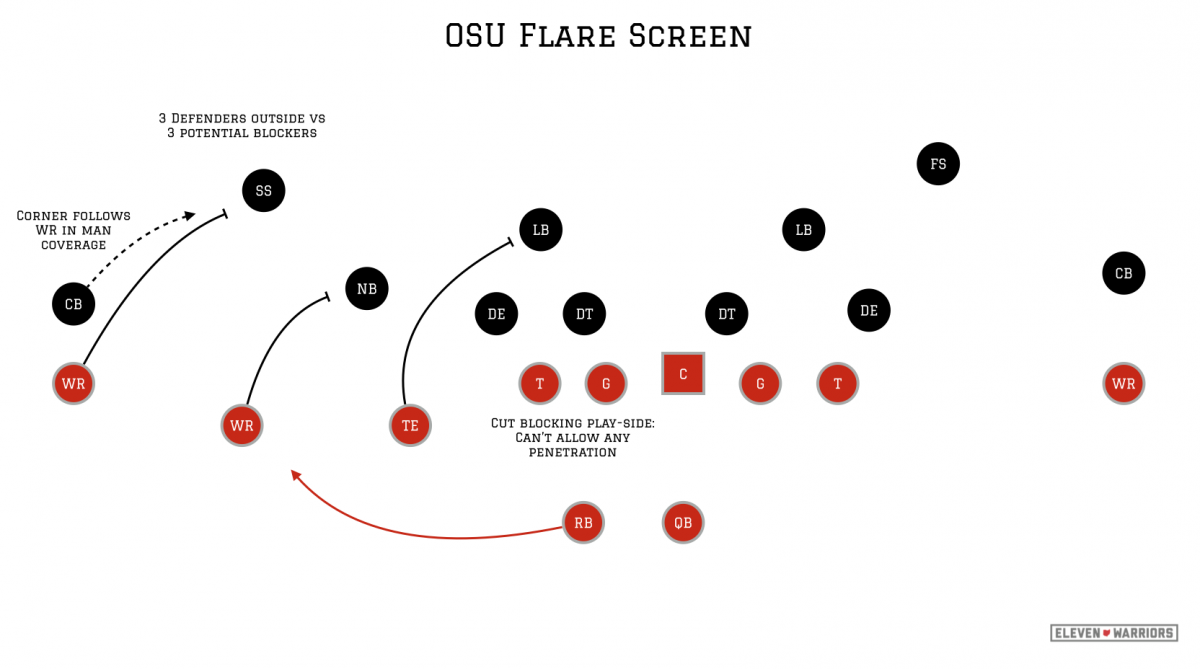

On the first possession, and on nearly every one that followed that afternoon against the Flashes, the Buckeyes would call for the flare screen, attacking their numerical advantage to one side.

With three receivers to one side matching up against three defenders (often a cornerback, safety, and a nickel or linebacker), the defense would need to either beat a blocker in a one-on-one situation or rely on an inside player like a linebacker or safety to come all the way out to make a tackle. Needless to say, the Buckeyes almost always held an advantage in that instance.

Elliott and Samuel would combine for eight catches that afternoon, setting a new precedent for production from the position. Meyer and his staff loved to open games with the play, so much so that it became a focal point of opposing game plans.

Oregon effectively sniffed it out twice on the first drive of the national championship game, not allowing Cardale Jones to even get the ball away either time. But that meant defenders were flying to the outside, leaving the interior vulnerable against the inside running game, as Elliott would exploit all night.

As such, the Buckeyes were forced to find new ways to build in the flare screen. One of the best ways to do so was through motion. Since Meyer and his staff only run the flare behind three blocking wide-outs, sometimes that meant motioning a slot receiver across the formation before the snap, turning a 2x2 alignment into the 3x1 they needed and turning the motion-man into a lead-blocker.

Other times, the back himself would go in motion, releasing out wide early and forcing the defense to rotate over in time.

The defense is put in a serious bind here, as the inside linebackers can't simply follow the back since they must respect the running threat of the QB, meaning the free safety has to run nearly 30 yards to make a tackle.

The flare screen acted as an extension of the running game, playing the same role as a long toss-sweep may have in the old days, looking to get the back to the outside. But it also built confidence for both of the young, inexperienced quarterbacks the Buckeyes would put under center.

After failing multiple times to find the back out in the wide open flats against Virginia Tech, the OSU coaches clearly taught JT Barrett to look for the back after progressing through his reads.

On the second play from scrimmage against Kent, Barrett progresses from left-to-right, resetting his feet four times as he moves from receiver-to-receiver, finally hitting Elliott who only needs to beat an inside linebacker in the open field to break a big gain. Barrett does have all the time in the world though, a luxury he didn't experience against the Hokies.

But as the season wore on, Elliott became a safety blanket for Barrett, as the young signal-caller regularly looked his way when pressure came.

Though his eyes are downfield the entire play on third-and-long, Barrett only needs a split-second to know Elliott has leaked out of the backfield as the pressure begins to arrive. As the pocket begins to collapse, Barrett only needs to locate the position of the man responsible for his running back, the linebacker, who is locked on the QB. He knows already where he's throwing the ball.

While averaging two catches per game isn't record-breaking, it does force the defense to take it into account, as Oregon did. As we look forward to the Buckeyes' rematch with Virginia Tech to open their title defense, Elliott's ability to catch the ball may well be the difference-maker.