Beginning this month, Eleven Warriors will publish a regular contribution from Dan P. McQuigg, the author of the book “Days of Yore: The Men of Scarlet and Gray,” featuring stories from Ohio State University’s rich athletic history. His first contribution tells the story of Fred Patterson, Ohio State’s first-ever Black football player.

As a young enslaved person, Charles R. Patterson apprenticed as a blacksmith and became regarded as the most capable blacksmith in his region. His expertise was an asset that his owner could, and did, turn into hard cash by leasing him out to others. Charles resented this exploitation and became determined to “escape the jaws of slavery.” Sometime in 1861, Charles slipped away from his plantation in Virginia and eventually found freedom after crossing the Ohio River.

Charles settled in Greenfield, Ohio, a significant way station on the Underground Railroad. There, his talents were in demand, and for the first time, he could trade his skills and labor for his own benefit. Over time he got married and with his wife Josephine, raised four daughters and two sons in Greenfield.

Black children weren’t permitted to attend high school in Greenfield when their oldest son Fred finished the eighth grade. When Fred went to the school on the first day of classes his freshman year, the superintendent denied him entrance to the school building. The Pattersons went to court to fight this injustice and forced the school district to provide Fred an education. The case helped influence Ohio legislators to reverse statutes that allowed Ohio school districts to provide different educational opportunities for white students than they did for Black students.

Fred found a welcoming student body when he entered Ohio State in the fall of 1889, along with a learning environment that seemed especially crafted for him. Oratory was a core component to campus life at the time and Fred – who was named after the great abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass – thrived as an orator. He possessed a “pleasing forcible style” and the persuasiveness of his arguments were purported to be “particularly interesting and strong.” He was equally adept at long, deeply researched presentations as he was at informal debates. He gave orations on subjects as wide-ranging as labor unrest, the constitutionality of presidential term limits, and he even defended small towns in a speech titled “Are Our Cities a Menace to American Civilization?”

Peers who described him as a “genial fellow that everybody knew and liked” elected him to honored positions such as The Lantern’s business manager and president of the class of 1893. His reputation as being trustworthy led to him being tapped as the sole arbiter for the 1891 “Cane Rush,” an annual ritual for bragging rights between the males of the freshmen and sophomore classes.

Military training was mandatory for all male students at the time and Fred was an exemplary cadet. As a freshman, he was appointed to a select company of OSU’s best cadets to represent the university in a prize drill competition against seasoned militia companies from Cincinnati, Springfield and Wooster. When Ohio State’s performance was judged superior, it marked the greatest triumph that anyone or anything representing Ohio State had earned to that date, and it was celebrated with great fanfare in Columbus.

Finding enough men to conduct a proper practice to prepare the varsity eleven was a constant struggle when Ohio State’s football program was just beginning.

Fred answered a plea that appeared in The Lantern in October 1890 that “urgently requested” students who were “foot ball-wards inclined” to form a “scrub team.” Fred and other scrubs may have been motivated by the thrill of competing or the camaraderie of being part of a team, or they may have simply succumbed to peer pressure questioning their school loyalty. Whatever the motivation, “scrub team” members certainly weren’t seeking gridiron glory.

Their job was described as being “unmercifully pummeled” by the varsity each day. The game was brutal, there were no helmets and most of the plays relied solely on “battering ram tactics.” Despite donating their sweat, blood and time, it was a thankless endeavor. Campus publications never mentioned them as being associated with the squad, and they didn’t appear in team photos. Hell, they even had to purchase tickets to watch the games.

In a sport where speed has always been coveted, Fred’s speed and raw abilities stood out. As a result, he was promoted to substitute at positions where his speed could be an asset: End, halfback and quarterback.

In an era when starters stayed in games so long as they remained conscious or weren’t otherwise incapacitated, the awful hand of fate played a role in what may have been Fred’s only appearance in a varsity game. Fred was thrust into the lineup for the Kenyon game when halfback Walter Landacre was called home due to the sudden death of his mother and OSU’s best athlete, Hobart Beatty, failed to show up on Thanksgiving Day in 1890.

Ohio State’s offense had been dormant in previous games that fall. The Buckeyes lost 50-0 to a team from Dayton to open the season, were humiliated by Wooster losing 64-0 in their first home game ever and then fell to Denison 14-0 in Granville.

Kickoff for the Thanksgiving Day clash with Kenyon was scheduled at 10 a.m. to ensure everyone could be home in time for feasts that afternoon. The Lantern observed that “a light fall of snow the night before” had made the field “slippery and covered with slush.” The sloppy conditions helped cause a muffed punt in Kenyon territory that Fred scooped up and carried to the end zone for a touchdown – the first by an African-American and only the sixth ever by an Ohio State player.

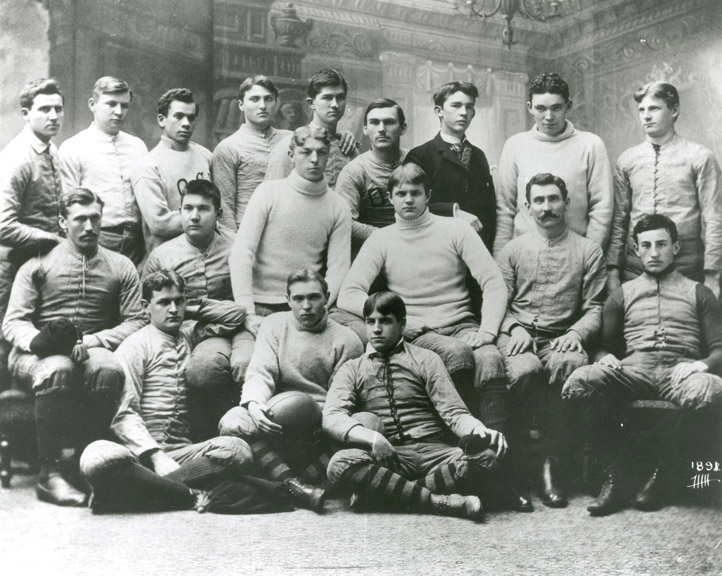

Fred wasn’t mentioned in any coverage of the 1891 season, but he’s listed as a substitute in the yearbook and appears in the team photo.

Perhaps Fred’s most memorable moment to his teammates occurred on Thanksgiving 1891 when he spoke at the postgame dinner following OSU’s 8-4 win over Denison. It was the Scarlet and Gray’s only victory in the two years that Fred was part of the team. In what a witness described as a “flow of wit and oratory,” Fred offered a rousing toast to “Professor Detmer’s Pig.”

It was a reference to a notorious Halloween prank weeks earlier when some students stole a hog from the agricultural school that had been used in cholera experiments. The pig ended up running away, never to be found and the angry professor and his German accent became the focus of a good deal of mockery. Detmer saw to it that the students that were involved, including a few scrub team members, were expelled. Old-timers talked about the prank for decades afterward, but Fred’s toast likely did as much to solidify the legendary status of the hoax as the prank itself.

Fred left Ohio State before his senior year and accepted a teaching job in Louisville, Kentucky in order to earn some income. He volunteered to serve in the Ohio National Guard during the Spanish-American War, but the war ended before his regiment was deployed to Cuba. He returned home to Greenfield after the war to help his father manage C.R. Patterson and Sons, a very successful carriage manufacturing company.

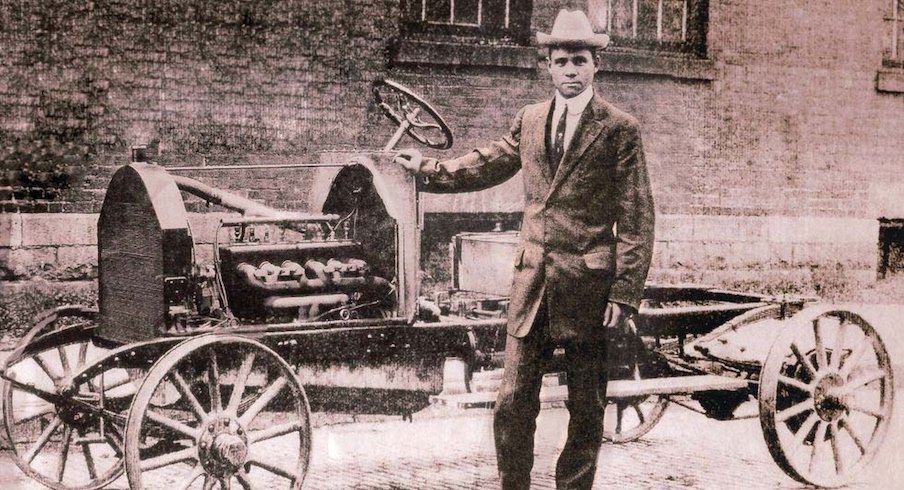

Fred took control of the company after his father died and soon began tinkering with the idea of building “horseless carriages.” He developed the Patterson-Greenfield automobile, the only car manufactured by an African-American owned company.

Patterson couldn't compete with bigger, well-funded companies, so he changed the focus of the company away from cars and began producing buses. One researcher has estimated that half of the school buses operating in Ohio were built by Patterson's company, the Greenfield Bus Body Company, by 1929. Fred ran the company until his death in 1932.

You can read more about Patterson’s remarkable life in “Days of Yore: The Men of Scarlet and Gray,” which is available for purchase on Amazon. You can follow McQuigg on Twitter @dpmcquigg.