“They were a different team by the end of the year.”

Such a phrase has been the common narrative when fans, coaches, and analysts alike take a look back at the 2014 national champions. Many point to the team that showed up in the Virginia Tech loss and compare it to the one that took the field against Wisconsin, Alabama, and Oregon.

While it's true that much of this development could be expected when looking at the youth at a number of critical positions, such as quarterback, offensive line, and in the secondary, the playbook on both sides of the ball grew as the year went on. Credit is certainly due to every member of the coaching staff for both the implementation of the base philosophies that have defined Urban Meyer teams for years, but also for a handful of small tweaks made throughout the year.

Many compare the schematic aspect of football to that of chess, with both sides looking to anticipate the moves of their opponent. After sustaining a huge blow early, this coaching staff effectively stayed one move ahead of their opponents all year long, making subtle adjustments throughout the season, and keeping their foes guessing incorrectly.

As we continue to look back at the historic run we witnessed from this bunch in scarlet and gray, let's focus on some of these subtle changes that many onlookers likely missed at the time.

Rotating Quarterbacks

Perhaps more than any other, the story of OSU's quarterbacks will come to be the headline for this team. After a shoulder injury knocked out Braxton Miller for the year before taking a single snap, JT Barrett did a fantastic job of taking his place, becoming a Heisman candidate of his own in the process.

While Barrett showed the intangible qualities immediately that you look for in a signal caller, he is actually a very different player than Miller, even though they're nearly identical in size and stature. Miller's best quality has always been his ability to run the football in space, having long been the most dangerous man to see in the open field for defenders.

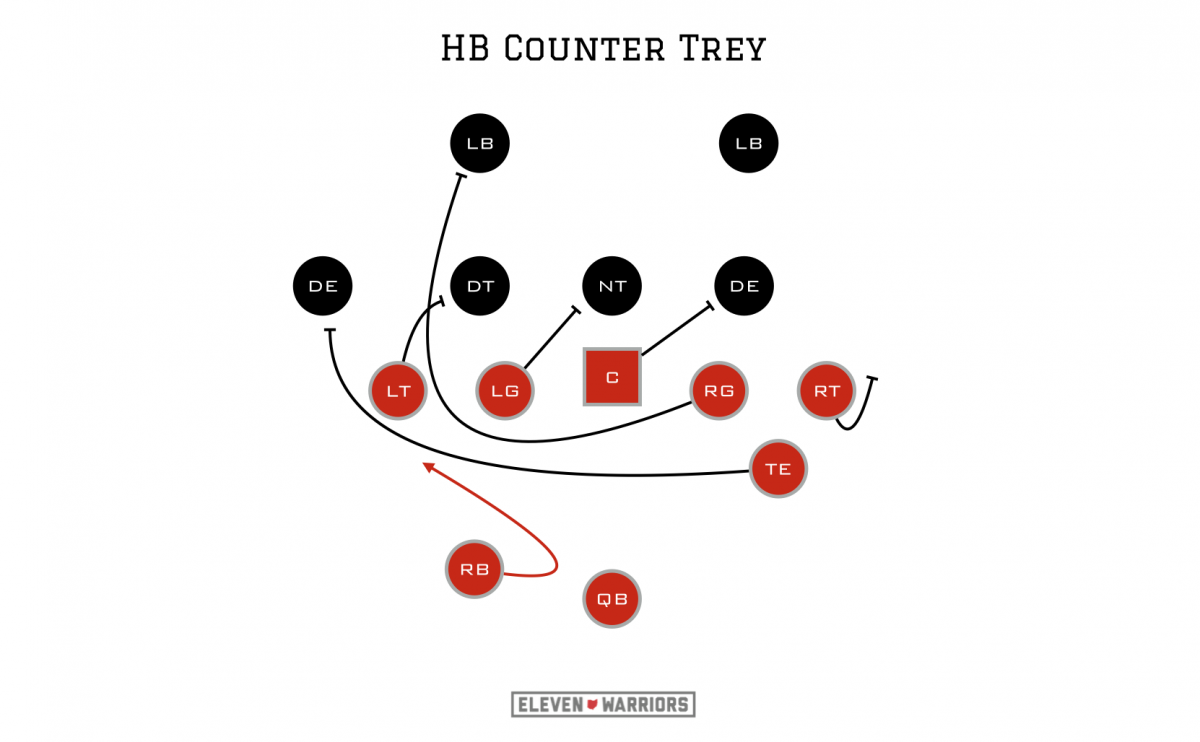

With such a natural ability to beat an opponent one-on-one, the Buckeyes had regularly featured Miller in designed runs where he was the ball carrier, such as the Counter-Trey (seen above) or the infamous outside zone sweep that was called on fourth down in the 2013 Big Ten title game. With a bruiser like Carlos Hyde to handle running inside, Miller was the Buckeyes' top threat to run on the outside, and his number was often called. During his first three years in Columbus, Miller had 15 carries or more in 16 games.

Early in 2014 when Barrett took the field in Miller's place, the Buckeyes had to change their strategy when it came to gaining yards on the ground. Barrett proved to be a very capable runner, yet one whose strength was in running north and south instead of laterally. With the emergence of Dontre Wilson and Jalin Marshall taking jet sweeps outside and Ezekiel Elliott handling duties between the tackles, Meyer and offensive coordinator Tom Herman were more selective about when to call on the running ability of their young QB.

Many coaches will abandon trying to run the quarterback if they don't have the personnel to do so effectively. But Meyer has long been a believer in the philosophy of winning through arithmetic, as the quarterback that simply hands the ball off without the threat of keeping it to run for himself effectively gives the defense a one-man advantage. To ensure that his teams always have this additional threat, Meyer has always recruited to fit his scheme, although the way in which his teams gain this advantage is fluid.

While Barrett wasn't often at the center of the OSU running game, the coaches still took advantage of his abilities. While he may not have been as quick as Miller, able to juke a defensive back in the open field, Barrett was effective inside, able to out-quick defensive linemen while strong enough to handle the impact from linebackers.

The Buckeyes regularly called on Barrett to carry the ball on designed draw plays: designed runs that appear at first to be a pass.

But Barrett also thrived in the read-option game, showing a great knack for making the correct decision on when to hand off and when to keep. This was the lone aspect of the OSU running game where Miller had struggled at times, often deciding to keep or give before the snap, leading to negative plays.

Against Penn State's top ranked rushing defense was this skill most apparent, as the Buckeyes had struggled to move the ball on the ground all night. Yet in the second half and especially overtime, Meyer and Herman called for the line and running back to run the tight zone, while leaving a defensive end unblocked. Barret consistently made this Nittany Lion defender wrong each time before finding the end zone twice in overtime.

As the season progressed, Barrett had become an established big play threat of his own, displaying the speed to outrun defenders in the open field once a crease had opened. But the OSU coaches were able to be selective about how they used him, as Ezekiel Elliott had begun to emerge as the devastating running threat that would make him a household name in January.

Barrett would nearly eclipse the 1,000 yard rushing mark while averaging nearly 5.5 yards-per-carry, an extremely efficient rate for a quarterback since sack yards count against their rushing totals. But as we all know, Barrett's season would also end prematurely with a broken ankle suffered against the Buckeyes' biggest rivals.

Thus would begin a three-game stretch for Cardale Jones that has made him a folk hero in the great state of Ohio. But with Jones under center, the OSU game plan would have to change yet again, as the big man from Cleveland offered a very different skill set than that of his predecessors at the position.

Though lacking the lateral quickness of Miller and straight-line speed of Barrett, Jones offered 250 lbs of pure mass to over-power opponents, something Meyer hadn't had in a quarterback since 2009. When lined up next to Jones, Elliott became the speed threat, able to beat opponents with a quick burst while the Glenville product acted as a short-yardage monster.

With this pair in the backfield, Meyer and Herman shrunk the playbook for Jones, regularly calling for the Power Read (aka "Inverted Veer") that leaves the front-side defensive end unblocked as the option man. If the end follows the running back on a sweep as his instincts often lead him to do, then Jones would follow a pulling backside guard straight ahead, effectively running the classic "Power-O" play with the quarterback now acting as the ball carrier.

Power Read had been one of the more successful play calls with Miller under center over the past two seasons, meaning it wasn't a new concept. However, of the five offensive linemen, quarterback (Jones), running back (Elliott), and tight end (Vannett or Heuerman), only two of those eight players had much experience running it in critical game situations.

In all three games Jones started, Power Read was a focal point in the Buckeye game, as the play allowed him to make one easy read, then quickly get upfield to gain four or five yards at a time. The play rarely saw Jones break any big runs, but it wore down defenders who weren't used to having to tackle such a massive runner.

But while Jones may not have been a huge threat to out-run opponents, he was still a major threat to pick up yards in the open field, thanks to his size. Very often, the Buckeye coaches packaged this threat into the passing game, shrinking the field for Jones and allowing him to make quick decisions before deciding to run.

As we saw early in the national championship game against Oregon, Jones was asked to read only half of the field, working deepest to shortest. If there was no open receiver, Jones was instructed to take off and pick up yards against a zone defender, leaving his opponent with the undesirable task of tackling a tank.

Often, it appeared the OSU staff called pass plays with the threat of Jones running in mind. Expecting Oregon to play a cover four zone defense against the pass, for instance, the Buckeyes ran the "Drive" concept to the short side of the field, with the outside receiver running a shallow cross while the slot to that side running a deeper cross behind him.

Knowing the linebacker would chase the shallow cross and the cornerback would drop to defend the deep cross, there would be no one in the flat to pick Jones if he took off. Almost immediately after taking a second to recognize the defense, Jones took off to that very spot, picking up 17 yards on this third down scramble.

All too often coaches treat play-calling as a mathematical equation, with the thinking of, "If the defense is doing A, and we're in scenario B, then we should call play C because that's worked in this situation before." But Meyer, Herman, and co-coordinator Ed Warinner deserve a ton of credit for adapting their existing playbook to suit the strengths of whoever was taking snaps.

Beating the Bear

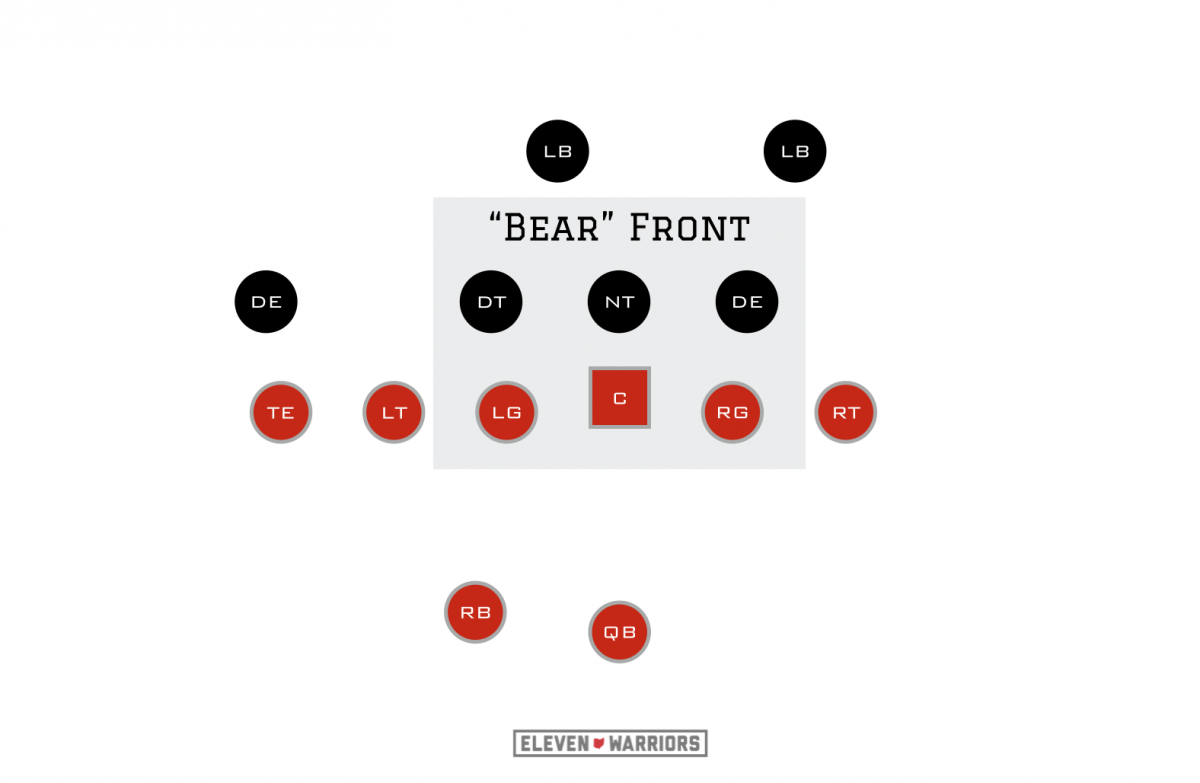

From a schematic standpoint, few things have tripped up the Buckeyes quite like the "Bear" front that Virginia Tech presented in their week two upset in Ohio Stadium. Knowing the Buckeyes had been extremely dependent on running the ball inside with the Tight Zone during the first two seasons under Meyer, the Hokies opened the game with the look that lines up a defensive lineman directly over the center as well as on the outside shoulder of both guards.

By plugging the middle with three bodies, the Hokies took away the natural bubble that the tight zone looks to attack, as well as keep their linebackers free to make tackles without having to fight off blockers. That evening the Buckeyes had difficulty establishing any consistency in the running game, as they were still breaking in four new starters on the offensive line.

There were few options to which the OSU offense could turn in response, and the Hokies had appeared to offer the blueprint of how to beat the Buckeyes. As was expected, nearly every opponent for the remainder of the season would follow suit, showing some variation of the Bear front in hopes of slowing down Elliott and the developing "slobs" up front.

As can be seen in the diagram above, the natural weak spots in the Bear front are over the tackles, meaning the Buckeyes had to find ways to attack more outside that they had been accustomed. The first response was to call for the speed option to attack the edge, as Ross detailed back in October.

But since Barrett lacked the same explosive lateral speed that Miller brought to the table, the speed option was fairly predictable and couldn't be called too regularly. So, the Buckeyes had to find ways to adapt their existing philosophies to the problem at hand.

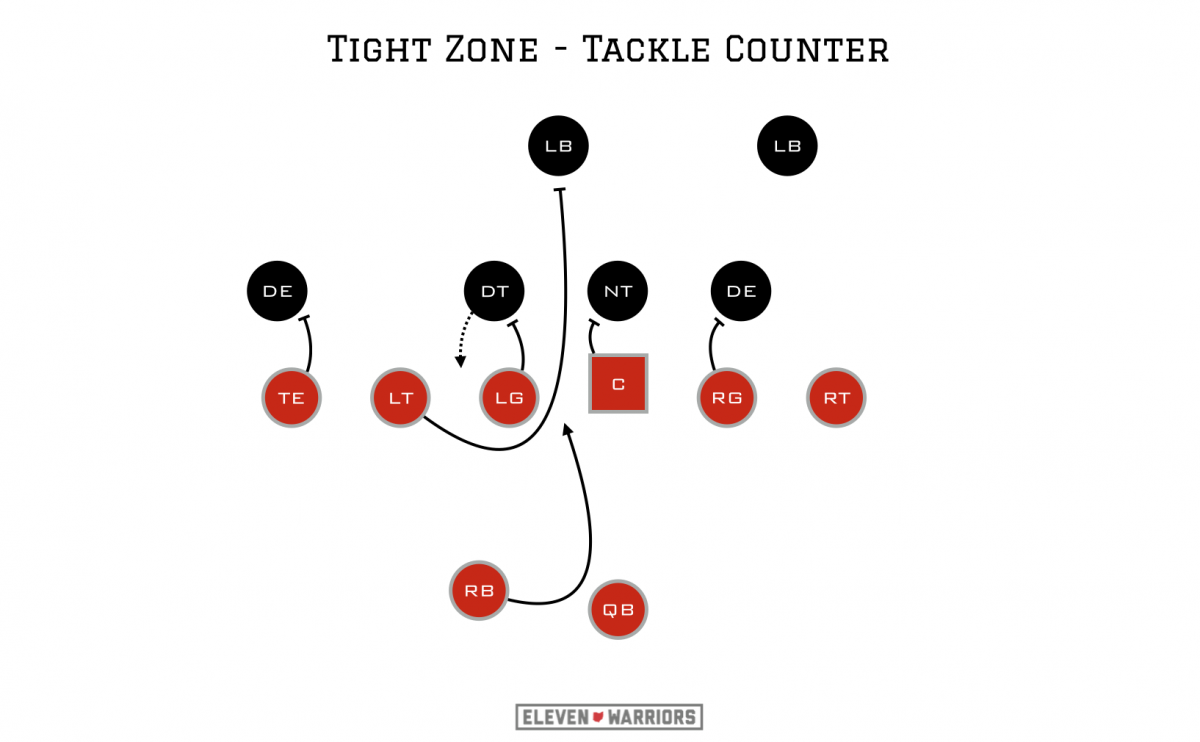

What came next were a pair of adjustments that called for tackles Taylor Decker (#68) and Darryl Baldwin (#76) to fill the role often played by the guards. The first was a simple tweak to the Tight Zone that allowed the guard to take advantage of the outside leverage of the defender over him, while the tackle would pull through the gap between the center and guard to take on the linebacker.

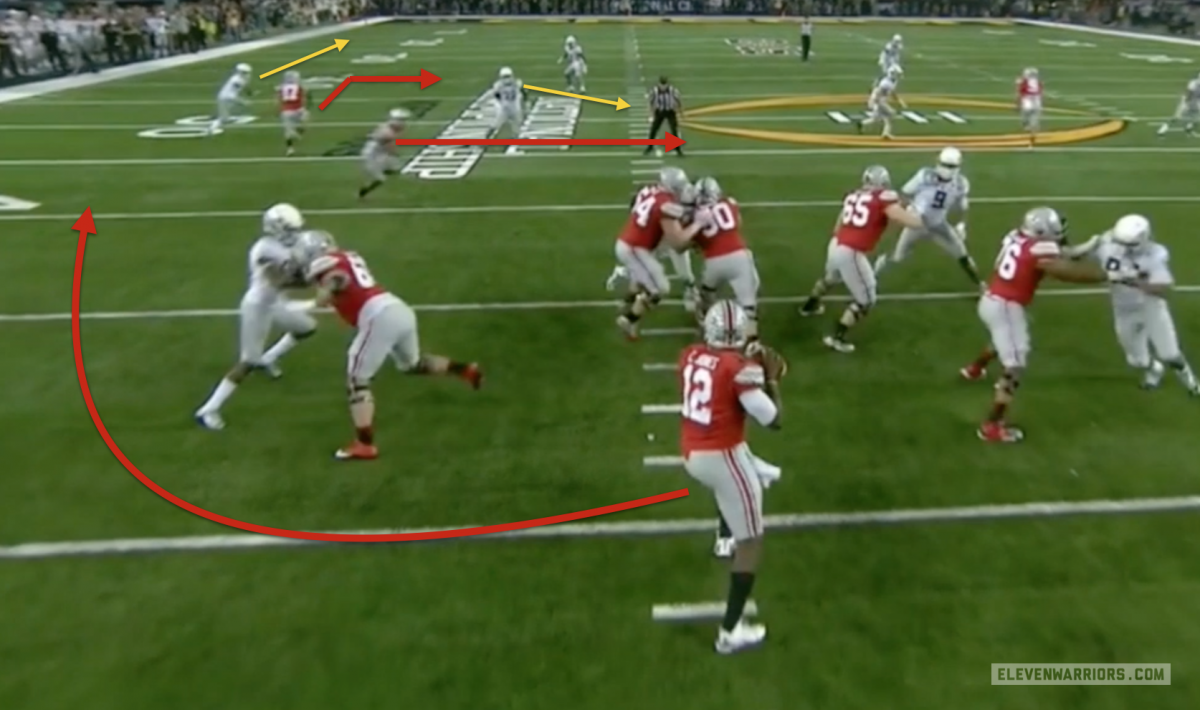

You can see it here in action against Cincinnati as the left side pairing of Decker and guard Pat Elflein lead to a 12-yard run from Elliott. One critical piece here is that Elliott lines up to the play-side, which is opposite from the traditional tight zone. By having to take a counter-step inside to receive the handoff before cutting back to his left, he gives Decker ample time to get upfield and lay his critical block on the middle linebacker.

But some of the additions to the offense weren't just handled by the offensive line. When teams would align in the Bear, they'd very often play man coverage behind it, daring the then-untested arm of Barrett to beat them deep. However, if the OSU receivers did take off on deep patterns, it often meant the "flat" areas outside the tackles would be wide open with no defenders having stayed there to guard a zone.

Almost immediately after the Virginia Tech debacle that saw the Buckeyes fail to take advantage of this open space, the staff began calling designed swing passes for Elliott. With six or seven defenders lined up inside and the secondary chasing wide receivers downfield, Elliott was basically being given an extremely wide handoff that would put him one on one in the open field against whichever opponent was assigned to him, a clear mismatch in favor of Ohio State.

As Barrett gained confidence and experience in the passing game, playing man coverage against the likes of Mike Thomas or Devin Smith began to look like a fool's errand, especially after the damage inflicted by the group in East Lansing. The Buckeyes often would see opponents open with the Bear front at the beginning of games, only to find that OSU had numerous counter-moves already in place to beat it.

But looking for ways to beat the Bear became a blessing in disguise, as the staff found more and more ways to get the ball in the hands of Elliott, who in turn would become the engine of the Buckeye offense by year's end. One of the staple plays ran for Miller that we discussed above, Counter-Trey, was tweaked to make Elliott the ball carrier instead of a blocker.

Center Jacoby Boren along with the guard and tackle to the play-side would simply block the man to their inside gap, while the back-side guard would pull around and lead Elliott through the hole after the tight end kicks out the defensive end. Elliott should have a natural hole right where the tackle initially lined up, attacking that soft spot in the Bear.

The Counter Trey was a major part of the OSU game plan against Oregon, where Elliott racked up countless yards against the Ducks' three man front. By practicing against the Bear all year, the Buckeyes were comfortable in blocking the 3-4 defenses that they saw from Wisconsin, Alabama, and Oregon, as many of the same philosophies for beating that look would apply to facing any true nose tackle.

When the season started, the OSU offense was known for being a team dependent on the tight zone, with a few wrinkles mixed in. But since the unit was forced to adapt to beat the Bear front, the Buckeye running game had evolved into one of the most diverse game plans in college football, able to execute a variety of zone and gap-blocking schemes at any time.

The job done by Ed Warinner to teach a group that featured one star recruit in Decker, two recruits many thought weren't big or strong enough in Elflein and Boren, and two converted defensive linemen in Price and Baldwin is truly remarkable. While we'll spend the next six months wondering if Elliott can become OSU's eighth Heisman winner, let's recognize that he won't be able to do it without the bunch of hardworking slobs in front of him.

Author's note: Next week we'll look at similar adjustments made by Chris Ash and Luke Fickell on the defensive side of the ball.