What was once old is new again.

For those of you that have been visiting Eleven Warriors for years, the word 'Dave' may send shivers down your spine, thanks to the play-calling of former offensive coordinator Jim Bollman near the end of the Jim Tressel era. Though the Buckeyes regularly featured competitive teams with 1,000-yard rushers like Beanie Wells and Boom Herron in that time, fans were often displeased with the manner by which those yards were accumulated.

Much as it's no secret that Urban Meyer's current offense is based around inside zone-runs, Bollman and Tressel built theirs around 'Dave,' their name for the 'Power' concept that can be found in virtually every playbook in America. But just as defenses have spent the past two seasons scheming for ways to stop Meyer's favorite play, opponents at the end of Tressel's stint in Columbus focused on stopping this gap-blocking scheme most easily recognized by a pulling guard.

Yet what often separates good offenses from the pack is their ability to recognize and adjust to what a defense is doing. While Meyer has succeeded in defeating the looks brought his way, many OSU fans became so frustrated with Bollman's inability to do so that just running the play at all would spark anger within some fans.

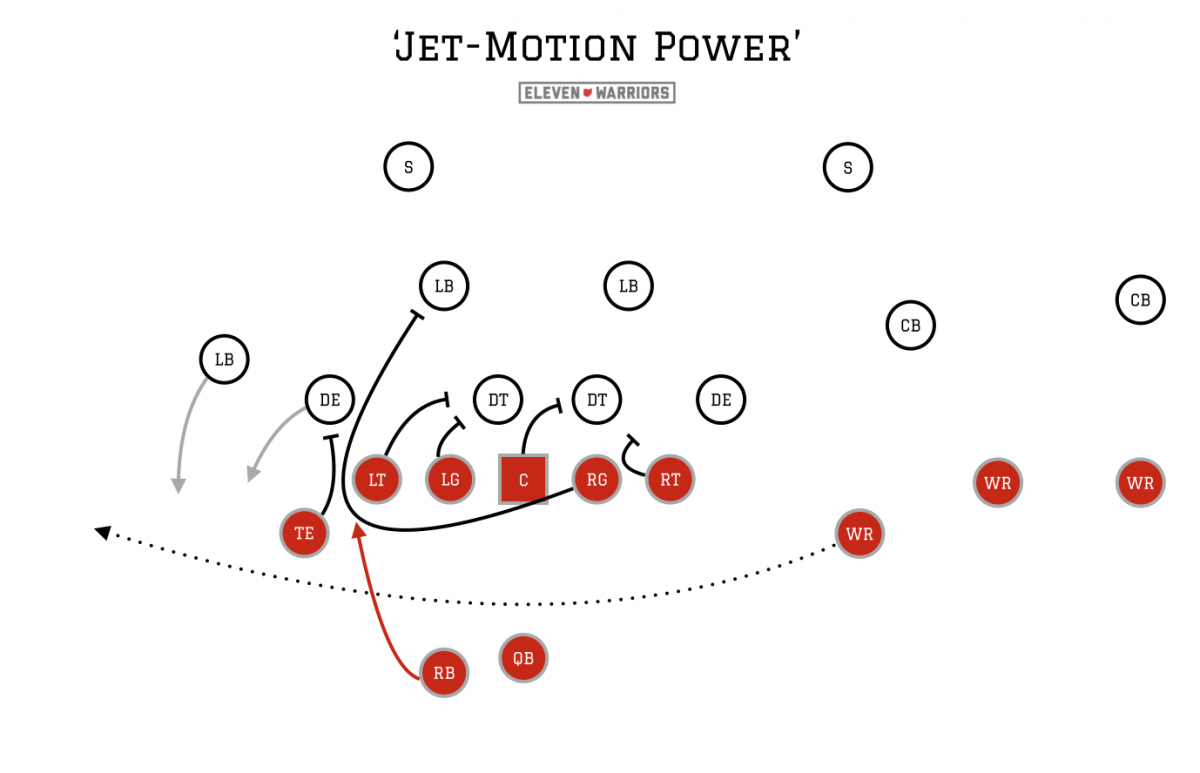

But the play itself is a simple one, and when blocked properly can be devastatingly effective. The center, guard and tackle to the side the ball will step inside, blocking 'down' and walling off any penetrating defenders. Meanwhile, the tight end seals off the outside of the gap between he and the tackle while the pulling guard leads the back through the hole, blocking the first defender that shows.

Zone blocking schemes, which Meyer seems to favor, calls for the entire line to block a zone in one direction or the other, regardless of the presence of a defender, and let the back choose the hole to follow based on how the play develops. Gap schemes like 'Power' and counter plays are designed to run through a very specific hole, and it's up to the line to ensure that space is open for the back.

This past Saturday in Bloomington, after yet another first half in which the Buckeye offense frequently stalled, the unit took the field early in the third quarter down 10-6. Although Cardale Jones had registered 200 passing yards to that point, Ezekiel Elliott and the OSU rushing attack had been largely held at bay. The Hoosiers had done an excellent job of forcing Jones to keep on option plays, choosing to let him beat them instead.

Facing a big third-and-two near midfield, OSU ensured that their Heisman Trophy candidate at running back would get the chance to do what he does best. However, instead of telegraphing the handoff, the OSU coaches would help him out by calling for left guard Pat Elflein to lead him on a version of the 'Power' play, with an assist from Dontre Wilson.

As Wilson comes in 'Jet' motion across the formation, the Buckeyes look as though they're set up perfectly for a sweep with Wilson taking a handoff before running behind Elliott and tight end Marcus Baugh around the left end. With both receivers to the right lined up on the line, the offense has all but given away that it's a run play, as the inside receiver would be ineligible in this alignment.

At the snap, both edge players on the Hoosier defense immediately step outside to play the handoff to Wilson, making Baugh's job of sealing the outside much easier. Meanwhile, left tackle Taylor Decker and left guard Billy Price double-team the nose tackle before Decker moves up to the linebacker at the next level.

But the defense doesn't appear to to expect a handoff to the running back on the left, given his alignment on that side of the quarterback. But after taking a slight jab-step and actually moving backwards to acclimate himself to the angle, Elliott follows Elflein through a wide-open gap, waiting for the pulling guard to pick up a block before making a quick, jump-cut outside and race to the end zone.

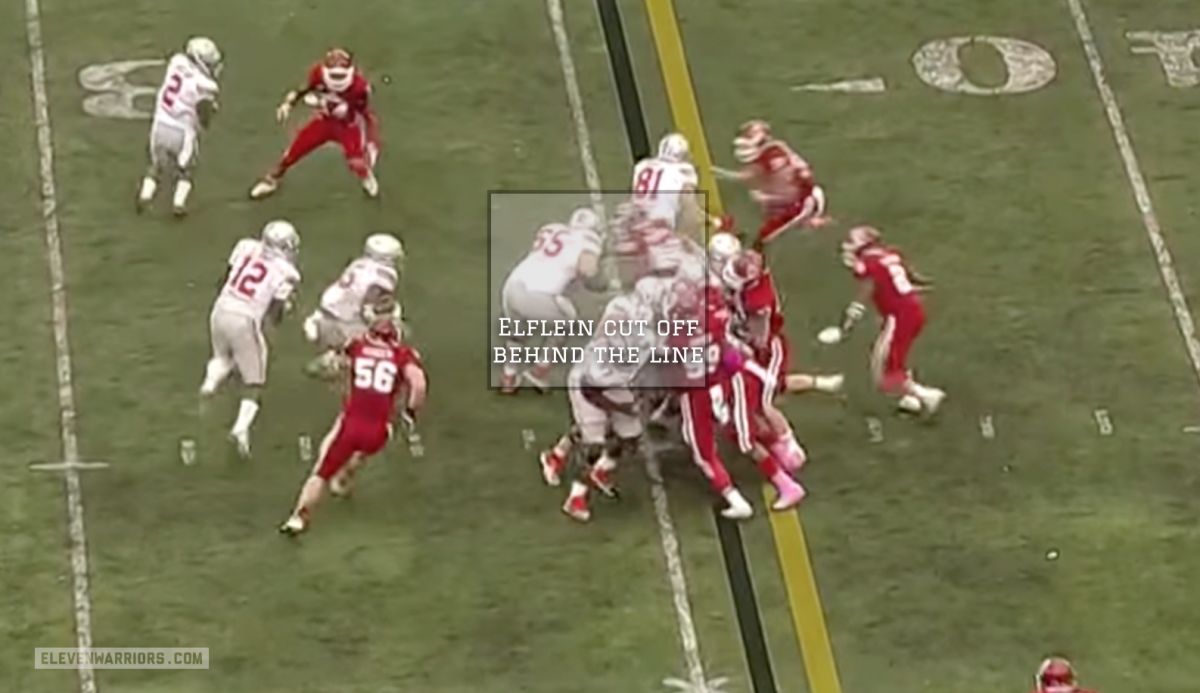

A few possessions later, the Buckeyes faced another critical short-yardage situation, this time a fourth-and-one from inside their own territory. While nearly everyone watching expected Jones to simply fall forward to pick up the inches needed to maintain possession, the offense quickly lined up in the same formation that had produced Elliott's long touchdown run.

While Wilson's motion this time still attracts a defender, the Hoosier defense didn't all bite, instead focusing on a potential inside run. But though Decker and Price did an excellent job once again of using leverage to collapse the interior of the defensive line, Elflein was met in the hole by a closing Indiana linebacker.

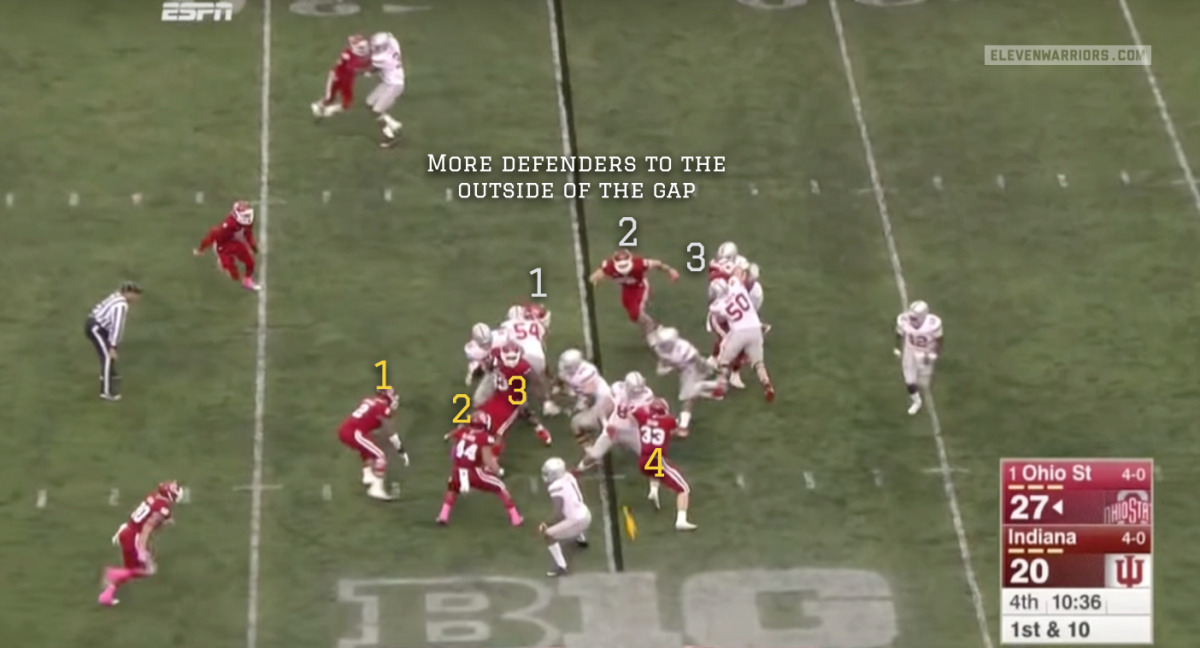

Given the short-yardage needed to get a first down, the Hoosier defense has more bodies at the point of attack than the Buckeyes. But moments like these are what make Elliott so highly regarded by NFL evaluators.

Though Elflein does a decent job of kicking out the linebacker in his path, Elliott cuts back at just the right moment to juke the unblocked safety and accelerate toward pay dirt.

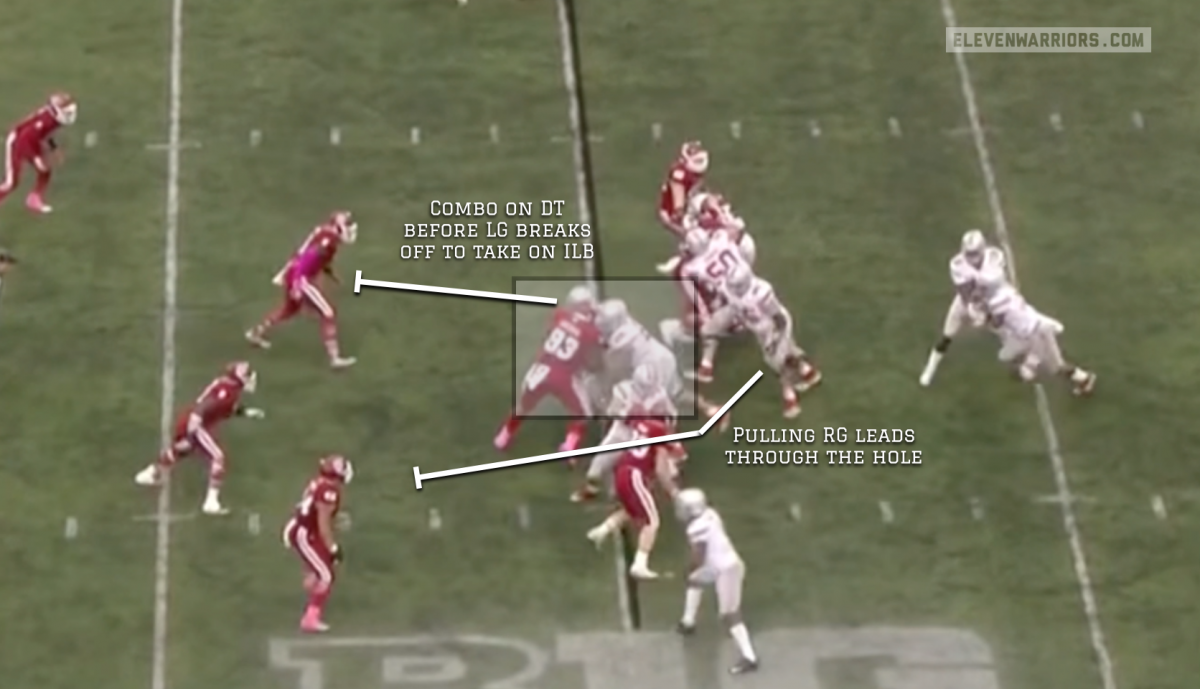

Though Power is designed to open a hole in the space where the tackle is lined up at the snap, there are still adjustments that can be made at the line based on the look shown by the defense. On Elliott's third touchdown run of the afternoon, the Buckeyes would call for Power, though this time from a different formation.

With two receivers and a tight end to the left, the Hoosiers would compensate with five players outside of the designed hole over the tackle. But the most important block in the concept is the 'down' block given by that tackle and the guard next to him.

After collapsing inside on the defensive tackle on both previous touchdown runs, Decker and Price would have a larger challenge this time, as the 'three-technique' defensive tackle between them would get an early jump on the snap. Instead of letting this man disrupt the entire play though, the duo did an excellent job of getting lower leverage and driving him backwards before Price would break off to take on a linebacker.

Thanks to Price's initial help, Decker turns his man outside, meaning Elliott's route is now a cutback lane to the inside. Elflein ensures that by sealing a man to the outside, giving the Hoosiers more defenders to the outside of the hole than back inside as they had on the previous two touchdowns.

Having been driven so far backward by Decker, the defensive tackle is unable to get any more than a shoulder on the passing Elliott. That contact proved to be just enough to throw off the pursuit angles of his IU teammates, but not enough to slow down the back who would once again show his ability to accelerate past defenders.

This is certainly not the first time the Buckeyes have called on 'Power' to help fend off a sluggish start on the road. In the 2013 comeback win over Northwestern, the Buckeyes dialed up the concept over and over as Carlos Hyde rumbled for 168 yards and three touchdowns of his own.

The parallels don't end there, however. That was Hyde's first 100-yard game of the season, and would help that offense define itself by a powerful inside and out rushing attack of El Guapo and Braxton Miller.

Fast forward back to this fall and you'll find lots of fans and pundits alike that have been waiting for not only Ezekiel Elliott to take over a game, but for Ohio State as a whole to find its identity. Now that the Buckeyes have shown that they're both willing and able to beat an opponent with Power and other gap schemes, they'll get better looks for their zone runs, as defenses can't go all in to stop them.

After a month of experimenting with the all the tools at their disposal, it's safe to expect Meyer and his staff to finally center the offense around Elliott and the interior running game once again. From there we can expect Jones and the play-action passing game to re-emerge as well, and the Buckeyes might live up to their heavy preseason billing.

But the problems with the offense was never what was on a chalkboard in a playbook. No scheme will work if a defense is designed to take it away, as nearly every opponent the Buckeyes have faced this year have attempted to do against zone-running schemes.

However, when trying hard to take away one concept, they're left wide open to the attack of another, which is why balance in play-calling is so important. Jim Bollman's offense didn't succeed because the idea of pulling a guard to lead block is a bad one, but rather that everyone in every stadium he entered knew that it was coming.