Ohio State adds another top-100 safety as Simeon Caldwell commits to the Buckeyes.

Although he was consistently benched whenever his team reached the red zone, Cardale Jones played his best game yet in an Ohio State uniform Saturday.

Meanwhile, J.T. Barrett finally looked like the player that set 19 school records and won so many awards in 2014. Though history has taught us to believe that a two-quarterback system shouldn't be successful, the Buckeye offense finally looked like the unit that fans have been waiting for in Saturday's victory over Maryland, beating up opponents with an inside running game before attacking downfield in the passing game.

While neither player had seemed totally comfortable when under center this fall, it was plain to see that the system as a whole lacked a cohesion and understanding of who they were and what they did best until now. With Tom Herman's departure, many wondered (aloud) if the Buckeyes could still find a winning recipe, discounting the fact that Urban Meyer has always been heavily involved in the decision-making processes of his offense.

As one of the leading innovators of the 'spread-option' offenses that have taken over the game in the past 15 years, Meyer has long been known for his ability to use the quarterback in the running game to gain a numeric advantage over the defense. At the same time though, he has also preached a philosophy of spreading the ball around to his play-makers, ensuring they have the ability to leave their mark on a game.

Yet this fall, those two ideas have seemingly been at odds. Thanks to the sheer amount of talent at their disposal, the Buckeye offense always seemed to be forcing the ball into the hands of players like Braxton Miller or Curtis Samuel, making an effort to get them involved while simultaneously removing both rhythm and identity from the unit as a whole. Add in the countless different defensive looks being thrown their way every week and it's not a surprise that there wasn't a single core concept or play upon which the Buckeyes could depend to pick up yards when they absolutely needed it.

After spending a month trying to find out what pieces fit in where, Saturday's game plan to play Jones at quarterback outside the red zone and Barrett inside of it seemed like a last-ditch effort to find a solution for a stagnating offense. When looking just beyond the surface however, we can see that Meyer is simply doubling down on his two core beliefs.

In his limited playing time thus far, Jones has operated best when asked to make one, easy read in the passing game. In the previous week's win over Indiana, he hit a number of long throws simply by running two deep routes at the free safety and throwing to whichever player was left uncovered. That same idea allowed the OSU running game to get going against Maryland.

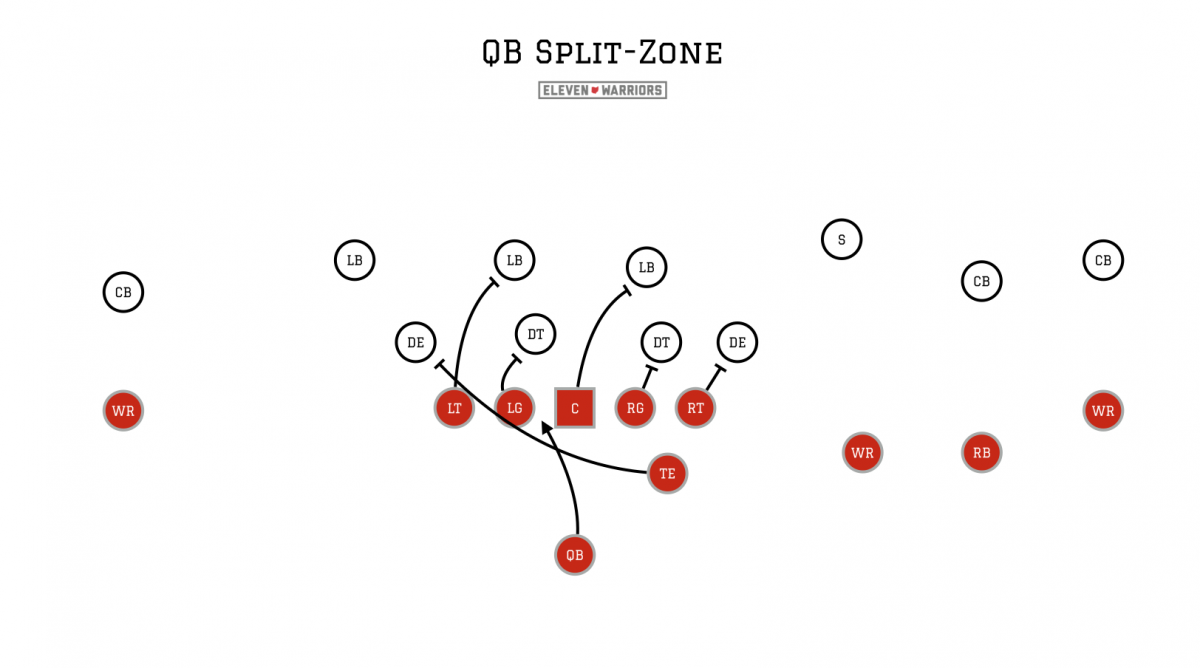

By now we've likely all heard about and seen packaged run-pass-options, in which the offensive line and running back execute a running play while the receivers run a short pass route. The concept has become so popular among 'spread' offenses that it's become a core part of some of the NFL's best units, and the 2014 OSU defense's ability to stop them was a big reason for their success.

The Buckeyes have run them for a few years now, but rarely with the same frequency we saw Saturday against Maryland. Jones has looked very uncomfortable running the traditional zone-read in which he's asked to run the football, but is quite the opposite when asked to use the option to open up a throwing lane.

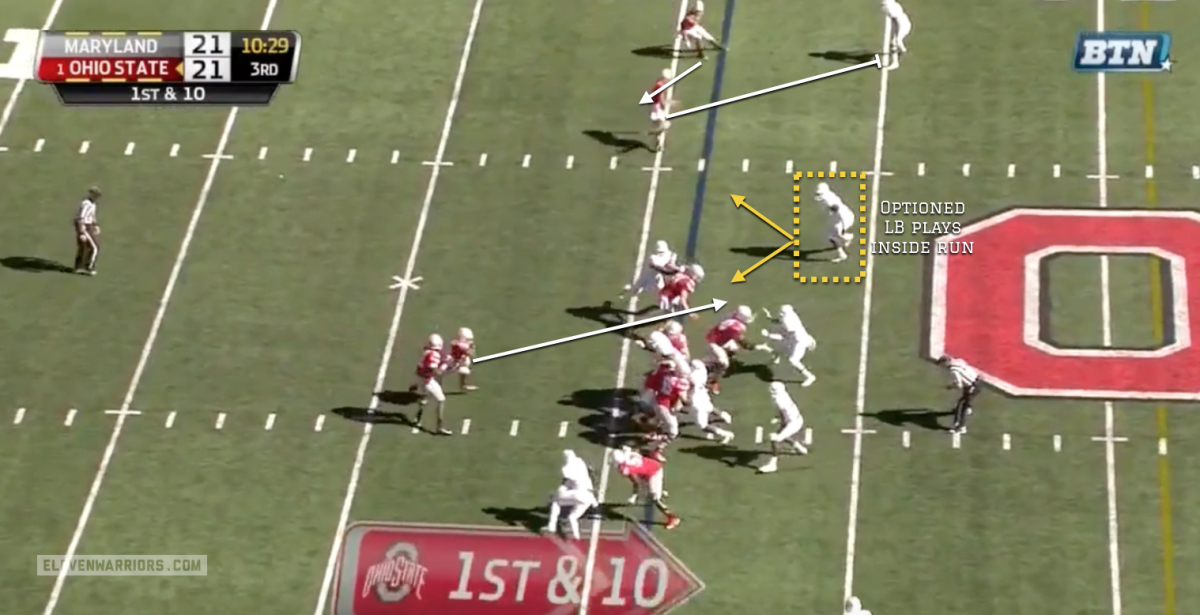

With Jones at the helm though, these plays become much more difficult to stop, given his ability to fire the ball out all the way across the field, which gives the receiver more open space in which to operate. With the outside linebacker diving inside to play the handoff to Ezekiel Elliott, there is only one defender within 20 yards to beat the blocker and take down the receiver on a quick screen.

Jones' big arm gives the Buckeyes a unique ability to stretch out the defense horizontally across the entire field, much in the same way good basketball teams move the ball around. No player can move faster than the ball can when it's being passed, so instead of trying to run it to the outside, line up across the entire 53-yard width of the field and let it do the work for you.

Once the defense gives up enough of these quick screens, that optioned man in the slot (often a linebacker or safety) will start to cheat outside to help cover them. Once this happens, the offensive line has an equal number of blockers as there are defenders, meaning no one is there to tackle the running back.

The beauty of this system is that there are multiple concepts that can be inserted into both the run or pass option. In the above examples we see different flash and bubble screens set up from two and three-wide looks, while a quick, three-step route to a player like Michael Thomas can be just as effective. Meanwhile, the offensive line can run-block in any number of ways, calling the tight zone as we see above, but also the "Power" play that crushed Indiana, or even the Buck Sweep on the outside.

This horizontal stretch not only opens up the interior running game and gets the ball to players like Miller, Samuel, and Marshall, but it opens up the deep passing game as well. Few players at any level of football have an ability to throw the ball downfield like Jones, but we had yet to see him complete these passes regularly this fall.

Whether spurred on by the loss of playing time near the goal line or another form of motivation, Jones was excellent in this phase of the game against Maryland, completing four passes of 20 yards or more. However, it's important to recognize the feast or famine nature of these plays.

After picking up a pair of first downs on their opening possession of the second half, the Buckeyes' drive stalled after Jones failed to hook up with any of his receivers downfield on three consecutive plays. Yet the big man from Cleveland showed patience and poise on all three occasions, throwing the ball away out of bounds, dumping off underneath to Elliott, and giving only his man a chance to make a play on a hurried throw that eventually fell incomplete.

After forcing a punt and getting the ball back near midfield, the Buckeyes would still take a shot downfield on their very next play, this time coming up big. Jones does an excellent job of surveying the entire field and moving his feet as he re-adjusts before finding Marshall streaking downfield as his third read on the play.

Coming into the day with five interceptions in as many games, Jones was careful with the ball, not turning it over once while completing 21-of-28 attempts for 291 yards, both career highs. It's no coincidence that as his fundamentals improve, so does the offense as a whole. Yet the inside-outside stretch of the option and ever-present vertical threat all complement each other.

One does not take precedence over the other, as evidenced by the fact that the Buckeyes racked up nearly 300 yards of total offense in the first half even while the defense held the running game nearly stagnant. The effective rushing attack that re-emerged in the third and fourth quarters was simply the result of Maryland trying to take away a passing game that had picked them apart.

Where Jones has struggled most though coming into the contest was inside the red zone, which lead to Barrett's playing time in that part of the field. With the vertical stretch taken away, the Buckeye offense took a different shape entirely.

Not only did Jones head for the sidelines, but one of the receivers often joined him, replaced by backup tight end Marcus Baugh. With 12 personnel (1 running back, 2 tight ends) on the field, the Buckeyes featured a much more physical look, one intent on over-powering a defense already worn out from the drive downfield.

With Barrett in the game, the defense can't depend on Elliott acting as the primary ball-carrier, allowing OSU to use formation and motion to gain a blocking advantage at the point of attack. When going big with two tight ends on the line and Elliott with him in the backfield, Barrett has eight blockers to run behind, often forcing a defensive back to come up and make the stop. Elliott's value as a blocker cannot be understated, as he regularly led the way for his quarterback while the line blocked an outside zone sweep.

But OSU also gained an advantage near the goal line with Barrett in the game by occasionally spreading out. In an empty formation, Barrett takes the direct snap and runs behind a motioning tight end to pick up short yardage.

Although nearly half the players on the field are on the outside, the outcome is determined by a fight in the trenches. The outside linebacker that shifts inside after the tight end's motion can't get around the edge quick enough, allowing Barrett to dive in the end zone for the score.

Thanks to a missed blocking assignment on the middle linebacker, Barrett was able to show off why he is so dangerous near the goal line. His vision and quickness as a runner led him to cut up through the hole allowing him to fall forward instead of getting stopped in the hole or trying to bounce outside as Jones often tried to do in similar situations.

From a schematic standpoint though, none of this is new. Every single play shown in these examples has been run multiple times since Meyer arrived in Columbus four years ago. The only change is in their organization.

Both players excel at making quick, but very different decisions. While there is no comparison physically between the Jones/Barrett duo and the way Meyer used Chris Leak and Tim Tebow on his 2006 Florida team, what he's asked of them is very similar. The roles of Jones and Leak are tasked with making one or two decisions before distributing the ball, while Tebow and Barrett are runners primarily that pose a threat to pass as well.

The organization given to the unit depending on who was in the game allowed for both to flourish, as neither was asked to do something outside their comfort zone while still providing enough of a threat in any direction to keep the defense on their toes. At the same time, the Buckeyes found a way to complement each player with a supporting cast suited to their specific needs.

Just as was the case then, there will be doubters that discount Meyer's ability to manage both players properly and motivate the unit as whole to follow each without question. But moving forward, this is an offensive philosophy that will be very difficult to defend.

Few, if any, of the remaining opponents on their schedule possess the necessary athleticism to match up with the Buckeyes across both the length and width of the entire field, which isn't new. In this new, two-quarterback system though, the offense is best set up to take advantage.