Long heralded as an innovator in his own right, Urban Meyer owes a great deal to those that came before him.

As any coach will tell you, it's rare to come up with a completely new concept in football's modern era. Rather, the new ideas we romanticize are often the brainchild of someone else.

Such is the case with the most successful 'guru' of spread offenses. Meyer, of course, has three national titles to his name, thanks in large part to a dominant attack that stretches a defense across the width of the field before pounding them inside with an inside running game that would've made Woody Hayes blush.

But although Meyer and his first staff at Bowling Green may have formalized their philosophy and style in the bowels of Doyt Perry Stadium throughout the winter of 2001, many of the signature concepts they'd include in their playbook came from valuable time spent with other coaches.

Much of Meyer's passing game can be traced to what John L. Smith and offensive coordinator Scott Linehan's 'one-back' offense was doing at the time in Louisville, while Clemson's then-offensive coordinator, Rich Rodriguez, was making the world spin with a new concept known as the 'zone read.' However, by then neither program had fully embodied what would become the spread offenses we now see at every level of the game the way Northwestern had. So, it should come as no surprise that Meyer also made the trip to learn from the Wildcats' head coach, Randy Walker, as he began developing his scheme.

There were a number of teams running shotgun formations with many receivers at the time, like Hal Mumme and Mike Leach's 'Air Raid' system, and a few collegiate programs were still running variations of the run-n-shoot, even though its popularity was fading. Those pass-happy systems were often capable of producing big points but lacked the balance needed to win on a consistent basis.

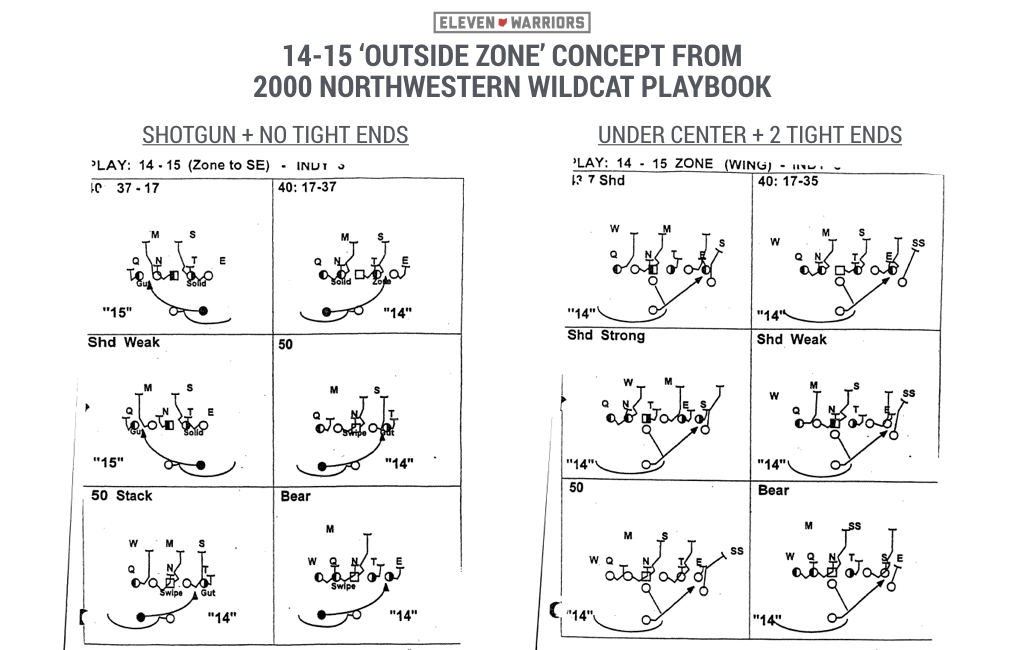

Instead, Walker and his right-hand man, Kevin Wilson, built an offense that still included all the same concepts as a 'traditional' offense, yet often adapted them to three and four receiver sets and an uptempo, no-huddle pace.

If the Wildcats saw their opponent give up a big gain on a zone-blocked running play from a back in the I-formation, they didn't have to come up with the spread equivalent when creating a game plan, they could simply line up and run the same play. Theirs just looked a little different.

Walker and Wilson had been teaching the same concepts for years, but their ability to adapt those plays to a new philosophy changed the game entirely. No single moment was more emblematic of what they had developed than their 54-51 upset win over Michigan in the fall of 2000.

Many consider that upset victory to be a pivotal moment in the history of the spread movement, as it forced the country to accept that teams could line up this way and still run the ball down your throat. As noted by Chris B. Brown,

"It was Walker that took the idea of "spread-to-run" and "zone-read" and systemized it. Again, Rodriguez had been a spread-to-pass guy originally, who just had this one really big idea for the run game. Walker and Wilson brought to it the traditionalist tinkerer mindset, as guys who had been coaching power, run-first football for years and were experts at blocking schemes, defensive fronts, and the like.

It was this marriage of the grand-new spread ideas with an old school attention to detail that helped Northwestern go 8-4 and beat Michigan in 2000, and it is this that guys like Urban Meyer and half the high school coaches in the country learned the bread and butter from.

...

This is why Walker deserves as much credit as Rodriguez for taking the spread mainstream. He showed how coaches could pretty much do what they already did -- and apply the lessons they'd already learned -- to a new environment, and to new success."

Wilson had been a critical player in the development of the Wildcats' 'Run N Gun' offense, drilling the offensive line to master the same run concepts seen in the NFL, yet still having the foresight and fortitude to adapt them to a new style. Such a mindset would be critical once he left Evanston for Norman, Oklahoma.

After winning a national title on the back of the 'Air Raid' system Leach installed in 1999, Bob Stoops and the Sooners looked to establish a more balanced attack upon Wilson's arrival in 2002. Though many members of the offensive coaching staff had been there for the pass-happy days of Leach and Mark Mangino, Wilson slowly began to integrate many of the tactics he'd been teaching for years, creating a hybrid system that incorporated the best parts of Walker's running game and Leach's aerial attack.

Now, with more talent at his disposal than he'd ever had at Miami University or Northwestern, Wilson's offenses became juggernauts. As co-coordinator with future San Diego State head coach Chuck Long, Wilson helped lead the Sooners to two B.C.S title game appearances and a Heisman trophy for quarterback Jason White in 2003.

However, Wilson's finest work came once he claimed full control of the OU offense. The 2008 Sooners were one of the most explosive units college football has ever seen, averaging nearly 550 yards per game. Once again, Wilson's quarterback, Sam Bradford, would win the Heisman while distributing the ball to talented skill players like DeMarco Murray and Jermaine Gresham.

Wilson and Bradford would attack teams with a bevy of looks from both the shotgun and under center. Much like Walker's playbook at Northwestern, the Sooners weren't running anything new, but simply adapting classic concepts to multiple personnel groupings and formations to keep defenses off-balance.

Throughout his tenure as the Sooners' play-caller, Wilson was often praised for unveiling 'new' concepts. However, more often than not these were simple tweaks to the same core concepts his teams had run for years. This 'toss' play, for instance, features the same basic 14/15 zone blocking scheme shown above, just with a slight change in technique for the quarterback and running back.

After three national title game appearances, two Heisman trophy winners, and Broyles award for assistant coach of the year while with the Sooners, Wilson was one of the most sought after coaches in America when Indiana hired him prior to the 2011 season. Upon his hiring, Meyer showered Wilson with praise for the work he'd done throughout his career, unafraid to show his admiration:

"If you look at Kevin Wilson's background, he was the one that learned from Rich Rodriguez, he brought it to Northwestern, and they had a great team... He brought the no huddle, up-tempo (to Oklahoma), and we (Florida) played them in the championship game several years ago, and the only chance we had was because we had forty days to prepare for that offense... He's one of the primary architects of that offense. Every answer, he has it, because he's the one that developed it. So I think that's a big loss (for Oklahoma), because I think he's a heck of a coach."

It came as no surprise to many that while in Bloomington, Wilson's offenses became a regular thorn in the sides of bigger programs like Ohio State as he fully embraced the original mindset that he and Walker had established at Northwestern. With less talent than bigger programs in the conference, the Hoosiers could hang with those programs thanks to game plans that stretched and confused defenses every week.

Unlike other spread coaches like Meyer or Rodriguez, though, Wilson rarely leaned on the quarterback to run the ball. While they still obviously had to pose a threat to pick up yardage with their legs in a zone-read, his QBs were asked to throw the ball far more, resulting in huge numbers for unheralded recruits like Nate Sudfeld.

Instead of forcing his QBs to master giant playbooks full of countless concepts, though, Wilson did the hard work for them, packaging a handful of simple concepts together into one play and creating simple reads.

But as you might expect a former offensive line coach, Wilson's Indiana teams always ran the ball well. Leaning on many of the same run concepts seen at Ohio State, Hoosier running backs Tevin Coleman, Jordan Howard, and Devine Redding all tore through the Big Ten, highlighted by Coleman's 2,036 yards and 15 rushing touchdowns in 2014.

Of course, things didn't work out as well for the Hoosiers in total during Wilson's tenure, posting a 26-47 record during that time. Though his teams could hang points on nearly anyone, his defenses ranked last in the Big Ten in four of six seasons after nearly all of the most talented recruits wound up on the offensive side of the ball.

Though many close to the game always assumed the Hoosiers were one defensive coordinator hire away from reaching the next level, allegations that Wilson mistreated some players emerged last fall, leading to his departure. But as his stock as a head coach fell dramatically, the fit to be Meyer's lead play-caller couldn't be better.

The two have borrowed concepts from one another throughout the past 17 years and their basic philosophies for attacking defenses are nearly identical. However, similar to the way Tom Herman found success as an outsider before joining Meyer in Columbus, Wilson has his own bank of knowledge to lean on.

After Greg Schiano reinvented the Buckeye pass defense upon his arrival in Columbus as a former head coach one year ago, Wilson will and should be expected to do the same with J.T. Barrett and the offense. The unit grew stale and unimaginative for large stretches of the past two seasons, likely as a result of groupthink and a lack of new ideas. Not only will Wilson immediately command respect in game-planning sessions from his subordinates, he already has it from the man that matters most: Meyer.