Time to Get to Work

Time to Get to Work

As we get closer to spring football and the time Urban Meyer & Co. will install their offense at Ohio State, it is worth examinging how a coaching staff should install their offense. This will be the only time that Meyer will teach his offense from scratch, so it is important to look at how it is done and should be done.

Pundit-types ofter refer approvingly to who has the most 'complex' offense and how the game of football continually becomes more 'complex.' Not only does this overstate football's schematic possibilities, it also has not proven to correlate to succes. This is particularly the case in college football, where practice time is limited. In this vein, Chris Brown has a fantastic piece detailing how Dana Holgerson and his 'Air Raid' cohorts install their entire offense in three days. I recommend the piece in full, but here are some key observations.

The first step is, whatever your offense is, to assign players to roles that fit them and have them develop those skills from one practice to the next, over the course of many months and years. The second step is to not make their job more difficult by changing their roles by moving them around or by installing too much offense — hence the three day rule.

I’ve used Holgorsen and his Airraid roots as the backdrop because these ideas were developed by Hal Mumme and Mike Leach, but they apply to every offense. After assigning players to their positions (RB, H-Back, Y, X, Z, etc) you install no more than a handful of plays each day, so that, for that day, the player’s job is obvious: learn your two or three assignments and do them over, and over, and over again. This is key for the receivers but even more for the offensive line — as you’ll see from the charts below the goal is to install only a couple of blocking schemes, both for runs and pass protection, each day, and then to repeat the process over and over again.

A few themes should emerge. One, broken down this way, a player’s job should be much easier, thus maximizing the “indy” or individual time (let’s cover the two or three assignments) and then the rest of the day is spent doing this job over and over again, and the player can even benefit from watching your teammates do it too. Second, the you can drive home the “hang our hat on it” plays by carrying one or two things over for every day. For Mike Leach’s Airraid, that was the mesh play, but for Dana Holgorsen it might be four verticals or something else. This is the other great part about this framework: once you have it, it’s easy enough to move a few pieces around and get the plan in place for a given year if talent shifts your focus.

Relatedly, Brown discusses how a coach should set up his installation to build upon itself.

Note how the formations build up to match the other plays: Day 1 only involves “balanced” sets, while Day 2 includes “unbalanced” trips and trey formations, with Day 3 being more focused on play-action — concepts not really present in the Airraid. But the theory is the same: the entire offense goes in in three days, and you could theoretically scrimmage on Day 4. You wouldn’t of course, you’d go right back to teaching and maximizing the repetitions.

How does this apply to Meyer?

Fortunately for our purposes, we have several of Meyer's old (and comprehensive) playbooks to examine. Meyer's 2004 Utah playbook, for instance, includes his Spring Practice schedule for his offense's installation. While the philosophy and individual plays have undoubtably been tweaked, it nonetheless provides a glimpse into Meyer's installation philosphy and will serve as our guide.

Meyer installed his base offense at Utah in six practices. Meyer took the same approach to building the offense outward as Brown describes. Every day, Meyer installs two to three: 1) formations; 2) motions; 3) run plays; 4) protections; 5) quick game; 6) dropback game; and 7) "screen/deceptives." Each day builds off the previous day. For instance, Day 1 begins with Meyer's basic 3 x 1 and 4 x 1 shotgun formations: doubles and trips with and without a tight end. The run plays are also of the same 'family.' Both speed option and zone read employ zone blocking, providing the offensive line repetitions. The downhill routes are all variants of four verticals, providing the base of the route tree for future days.

Day 2 builds from there. On day 2, Meyer introduced his 'empty' formations. Meyer also introduces two plays that build off the zone read--the read with the H-back blocking back ("Fargo"), and the wrap and QB wrap, also known as 'dart.' Below, Charles Fisher from 'Fish Duck' explains how 'dart' builds upon the zone read and power.

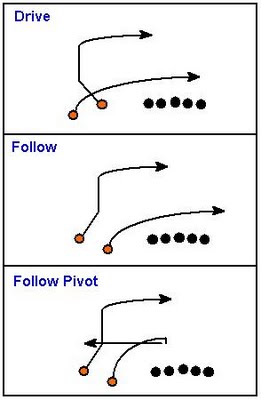

Meyer uses this day to introduce other staple pass plays, such as the cross routes drive, follow, and follow-pivot. Note how these three routes build upon each other.

Day 2 is also the first day Meyer installs his constraint plays. A similar theme emerges in this area. The two reverses installed are based upon the two run plays installed day 1.

In other words, the goal is to constantly build upon what was previously introduced. This pattern continues for those six days. For example, the bunch formations and related plays are installed day 3, and the under center formation and plays such as power are introduced on day 4.

Play action is implemented on day 5. Thus, while perhaps not quite meeting the airraid ideal for simplicity, Meyer's installation process nonetheless shares the same goals. Very similar to the process Brown provides for 'spread-to-run' offenses, Meyer's installed formations and runs mesh for that particular day, and option plays are predicated upon the same blocking schemes as the base run plays installed, providing increased repetitions for the offensive line.

Constraint plays are installed on subsequent days after the base plays, meaning that the most important concepts are repped daily. While specifics may differ, look for Meyer to follow this template with Ohio State this spring.