Production facilities of great Elevator Brewing Co in Downtown Columbus

Production facilities of great Elevator Brewing Co in Downtown ColumbusAbout one in six FBS programs play in stadiums that sell beer during games, and about half of those stadiums are on campus.

Ohio Stadium has long been part of the sober on-campus majority, while as of last season, Mountaineer Field at Milan Puskar Stadium in Morgantown is not.

West Virginia cleared over half a million dollars in profit in its first season selling beer at Mountaineer home games while registering fewer campus arrests for the entire 2011 season than there were in Tuscaloosa just during the Alabama/LSU game.

While some schools have sold beer at home games for decades (Colorado State, which shares a city state with the Coors headquarters, will be selling beer for Rams games for the 37th year this fall) more universities are now looking for ways to increase revenues while relying less on state funding and endowments that aren't getting bigger in our sluggish economy.

Last season was West Virginia's first selling beer at home games, and next season Minnesota will be bringing the brew to the Bank in a way that should be exponentially more successful than the last time they tried it.

The arguments for beer sales begin with money and end with selling alcohol in a controlled setting rather creating an environment for hidden-booze-in-the-pants fans. The argument against beer sales begins with concern over tying alcohol to a university brand (which is valid) and ends with an increase in entries to the police blotter (which is unsupported by evidence and therefore not valid).

With multi-billion dollar endowment, a strong balance sheet and a football program that already fills its huge stadium in good times and bad, Ohio State doesn't have to find new sources of revenue. However, the university is favorably positioned to pioneer stadium beer sales in a manner that transcends the conventional practice.

How popular was the new beer offering among Mountaineer fans? In West Virginia's home opener the concession sales breakdown went like this: 18,803 bottles of water, 2,906 sodas, 8,908 frozen lemonades and 21,811 beers which comes out to about one total beer for every three fans.

According to WVU police chief Bob Roberts, there was no uptick in unruly fan behavior. The school set a concessions record that day moving $548,000 in snacks and drinks excluding beer.

Having booze as an option positively impacted the sales of all other products.

ending the beer ban, intelligently

Game day binge drinking and excessive consumption happens in bars and at tailgates where there is hard liquor available and no limit to the number of drinks that can be consumed. Both are environments that generally lack the control that is seen in stadiums.

Those arenas across the sporting spectrum curb their legal exposure to the consequences of inebriated patrons by passing the liability onto the providers, who smartly limit quantities. You can only buy two at a time.

Oval Brewing: "The Best Damn Beer in the Land™"

Oval Brewing: "The Best Damn Beer in the Land™"On top of that, the supply chain from the bottle to your mouth is a bit more complicated than it is at the bar or tailgate: You're competing with a lot more people for service.

It's what all game day drinkers have always understood: There is a significant difference between being drunk at a game and getting drunk at a game. The latter is not only much harder to do, it's also a lot more expensive and less efficient - unless you enjoy standing in long lines and paying mini-bar prices.

What West Virginia discovered in making its calculated decision heading into last year was that the restrictions were part of the problem. Allowing "pass-outs" (Ohio Stadium hasn't had them in forever and more schools that once had them are getting rid of them) sent fans back to tailgates and bars to essentially binge-drink before returning to their seats.

At the same time, ending pass-outs sent fans to their tailgates and bars for the rest of the day, leaving empty seats behind as they took their consumption and wallets to other non-stadium businesses.

The answer, especially with ticket prices that rival and often exceed those of professional sporting events, was to provide the same amenities along with the control and responsibilities that are found at pay-league stadiums.

In anticipation of its new sudsy game days, West Virginia expanded its restrooms, added surveillance cameras and trained its staff. Its concessionaire, Sodexo, assumed the liability risk associated with alcohol sales which is a common arrangement.

Sodexo also has the business at Ohio Stadium, and its restrooms were expanded a decade ago (though lines remain, as they do at every single other stadium in the world).

A recent, albeit inadequately-powered study found that 8% of fans leave stadiums with a BAC above the legal limit for operating machinery. That's equates to about 8,800 people leaving Ohio Stadium who should not drive. Odds of being above the limit were predictably higher for younger fans, tailgaters and during night games.

The flip side is that 92% of fans were not too drunk to drive. The law of big numbers works to Ohio Stadium's advantage: 8,800 drunks would seem ripe for problems if not for the over-200,000 sober eyeballs that are on them, many of which would not be shy in reporting abberant behavior to the Shoe's already gigantic security crew.

Do something great

It would be very easy for Ohio State to follow the same model that West Virginia and many others have already taken, but the university can be far more innovative than simply following a cleared path to an uptick in game day revenue.

Sodexo would have no problem conveniently calling in some trucks from the local Anheuser-Busch brewery on Shrock Road. You can be confident that AB would happily supply Buckeye game days with some of the same mass-produced swill that's already pouring en masse out of most bars and tailgates.

Doing so would categorically qualify as supporting local business, except that AB is actually based in St. Louis, owned by InBev in Belgium and does about $17B a year in business.

Instead of bringing Big Beer into the Shoe, why not end the alcohol ban by devising an entirely new and innovative method of supporting Ohio-based small businesses?

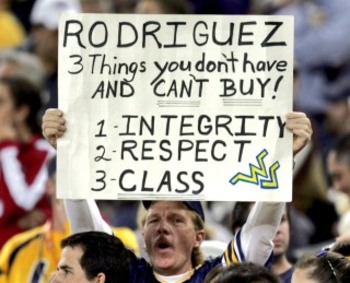

...but RichRod can buy beer at West Virginia home football games.

...but RichRod can buy beer at West Virginia home football games.Ohio is a treasure trove of breweries, the majority of which call the Buckeye state their home while meeting the small business definition.

These companies are founded and run by in-state entrepreneurs who - in addition to making high-quality/small-batch products - also make jobs.

When channels open up to increase business, their needs to maintain that growth increase which in turn feeds the job market. What better opportunity for them could there be than access to the large captive audience that the Shoe supplies each fall?

"(Ohio Stadium) could really open up a market to a lot of people that craft brewers normally cannot penetrate or even reach," said Adam Benner of the Oval Brewing Company. "At Nationwide (Arena) they offer one craft brewer and everything else is served by Bud/Miller/Coors."

Microbrews are for generally seen as products for drinking palates with greater sophistication rarely found among, say, undergraduate students. When I was in college I feigned elegance with Killian's Red, a cheap and disingenuous mass-produced substitute for refinement that nonetheless made me feel like carrying a gold pocket watch and wearing a monocle.

Regardless, consuming even a pretend-craft beer is generally done in the slower local boulevards, while watery American pilsners are built for speed of the HOV lanes to inebriation and extended bathroom lines.

"A lot of other arenas are now getting into offering craft beer selection," said Benner. "Target Field (home of the Minnesota Twins) is one; they now have a beer that's only sold at the stadium called Bandwagon."

"There are all kinds of opportunities for collaboration with the small guys instead of exclusively awarding large pouring contracts to Bud/Miller/Coors."

That kind of craft product exclusivity at Target Field may violate the NCAA's rule against alcohol marketing, however offering otherwise commercially available products is well within the NCAA's compliance guidelines.

paying forward responsibly

Ohio State football has been used to generate money for its smaller, in-state partners for years. Usually agents for those collaborators arrive wearing helmets and leave with what's only perceived to be a loss.

It's why Youngstown State came to the Horseshoe twice to play what only appeared to be a football game; both meetings were actually the transfer of wealth to a smaller institution that just happened to have its former AD coaching the Buckeyes on the opposite sideline.

Ohio MAC schools share state funding with Ohio State, whose stadium presents the largest opportunity for revenue collection in the state and one of the largest in the world. This is at the core of why the Buckeyes don't do home-and-homes with Miami, Bowling Green, Toledo, Akron or Ohio: It's bad business for both sides.

Just like a CFB playoff: OSU is sitting on a golden opportunity.

Just like a CFB playoff: OSU is sitting on a golden opportunity.The AD is not opposed to these kinds of favors, even when it doesn't benefit in-state schools: When the Buckeyes hosted Eastern Michigan, it was extending its ample game day payout to the school that just so happened to grant Gene Smith his first athletic department position (and note that Eastern Michigan extends its in-state tuition rates to Ohio residents).

It's time to amplify OSU's outreach to Ohio's small businesses. It's time to think unconventionally, outside of sterile corporate dispensation contracts and rigid distribution agreements.

There are creative and transparent ways to limit exposure to the university, just as there are precedents for doing so. In making this a small business opportunity, the only difference here would be scale and ingenuity: Ohio State would be bigger and more innovative than its precedents.

Aggregate participating brewers to share liability coverage. Create exclusionary criteria for involvement to maintain accordance with both stadium rules and program participation. Install standard cut-off times and adjust it accordingly for the odd night game. Establish quantitative metrics and tracking to gauge how successful the program is and if any uptick in adverse behavior can be tied to it.

It's not that complicated, nor should it be too difficult to integrate into existing stadium practices. The best part of having Ohio small businesses shoulder the exercise of bringing their products to the Shoe is that the increase in concessions revenue isn't the best part. It's exposure these local producers will have to heavily-biased consumers of Ohio's most beloved local product.

Showcasing Ohio-made products and manufacturers without violating the NCAA's on-campus alcohol marketing ban or compromising fan safety is a win for all game day stakeholders.

Evidence shows that doing so would provide greater control over alcohol consumption. The detractors to the idea of stadium beer sales are poorly informed to the benefits of unlocking and controlling the flow of suds to fans. And locally-manufactured craft beer at a stadium markup is hardly the optimal vehicle for binge drinking.

"If the deterrent from the university standpoint is that they cannot justify selling cheaper beer for fear of bad behavior, then they should explore more practical options," said Benner. "Craft beer may actually assist in shrinking the horde of intoxicated fans."

"Using local companies to accomplish this would also infuse local businesses with significant growth opportunities they normally could not achieve on their own."