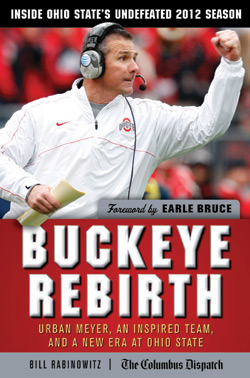

Dispatch OSU football beat writer Bill Rabinowitz' book about the 2012 season, "Buckeye Rebirth: Urban Meyer, an Inspired Team, and a New Era at Ohio State," chronicles the start of the Urban Meyer era at Ohio State.

With the Penn State game coming up on Saturday, we thought our readers would be interested in reading Rabinowitz's chapter about the 2012 game against the Nittany Lions, one of the more memorable ones from last season.

For the book, Rabinowitz interviewed the grandmother of Gary Curtis, the deceased friend who inspired Ryan Shazier to wear Curtis' old number and make the pivotal play of the game. The chapter, like the rest of the book, has details about Ohio State's season never previously reported.

"Buckeye Rebirth" is available through Amazon, the Columbus Dispatch and other fine retailers.

CHAPTER 19 – PENN STATE: FOR GARY

When Gary Curtis died on April 24, 2012, Ryan Shazier knew he wanted to do something big to honor his friend’s memory. Curtis never played a game or took a practice rep for the Plantation (Florida) High School football team, but he was as instrumental to the Colonels as anybody in the program. Nobody loved football more than Curtis. Technically, he was a team manager. Really, he was the team inspiration. Despite the Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy that confined him to a wheelchair, Curtis was revered as a full-fledged member of the team, complete with uniform No. 48. When Shazier transferred from Pompano Beach to Plantation as a sophomore, he didn’t understand who Curtis was or why he was always at practice. The scorching south Florida heat didn’t faze Curtis, nor did the torrential rainstorms that are a regular part of life there.

“He was in a wheelchair, and I always wondered who he was,” Shazier said.

Shazier is an outgoing guy. Meyer said he’s the kind of guy his wife always wants to give a hug. Curtis also had an upbeat personality as well. They struck up a friendship.

“I’d always talk to him,” Shazier said. “He’d always play video games with us.”

Gary was six when was diagnosed. He could still walk at that age, but as the disease progressed, he had to rely on a wheelchair. That wasn’t all Curtis had to overcome.

“His mother was a drug addict and the courts took Gary away from his mom and gave him to me,” said Pat Curtis, Gary’s grandmother.

Pat wanted Gary to experience life fully, and she never treated his disease as a disability. Gary knew his life would be short. People afflicted with Duchenne’s typically die by age 25. When Gary was 11, he came home from school and said to his grandma, “Do you know my disease is fatal? It means I’m going to die.”

Pat told Gary that everybody dies eventually, that it was more important to live each day to its fullest. Gary replied, “Oh, okay,” and that was that.

“As he got older and realized he was going to be in a wheelchair, he would be like, ‘Why me?’” Pat said. “But we got through that and we never looked back. It probably took a couple years. He couldn’t run. He couldn’t play football. He couldn’t do the things other kids could do. He would get disappointed, and we would talk it through.

“I said, ‘God didn’t give you anything you can’t handle, Gary. God put you on this earth for a purpose. Maybe you’re going to help someone and don’t realize how much you’re helping them.’ Maybe that stuck with him, that he was put on this earth to help people.”

Pat recalled how excited Gary was when a football player invited him to his birthday party. When Pat later saw the player at the grocery, she thanked him.

“Mrs. Curtis,” the boy said, “if it wasn’t for Gary, I wouldn’t be where I am today. I was ready to quit, and Gary said, ‘Absolutely not. Do you know how lucky you are, the way you can throw the football?’”

Shazier never needed to be encouraged to play football. He always loved it. But Curtis provided extra motivation.

“We used to always play for him in high school because he wanted it so bad but he could never get to play,” Shazier said. “He was always there for us in football, so I was always there for him outside of football.”

Shazier may have been especially empathetic to Curtis because he knows what it’s like to be different. When he was five, Shazier was diagnosed with Alopecia, a condition that causes loss of hair.

“I was the only bald kid in kindergarten,” Shazier said.

Shazier is now completely comfortable with having Alopecia— he even cracks jokes about it—but it him took several years to accept it fully. “Early in my football career, it helped me release my anger by playing instead of doing something stupid,” he said.

Shazier comes from an accomplished family. His father, Vernon, is a pastor and motivational speaker who serves as team chaplain for the Miami Dolphins.

“Ryan has always been a kid who, whatever he gets involved in, gives 110 percent,” Vernon said. “I’ve kind of raised him that way. Know what you’re committing to, because when you do, you have a responsibility to give it your all.”

If Ryan had a weakness as a kid, Vernon said, it was that he was too generous. He remembers having to replace his son’s cleats in middle school because he’d given his to a needy teammate. In that sense, he was a bit of a kindred spirit with Gary Curtis. But as Shazier blossomed as a player, Curtis’ health declined. In the spring of 2012, while Ryan was a freshman at Ohio State, Gary was put into hospice. He was 20 when he died.

“We had his memorial at the football field,” Pat Curtis said. “We waited until June when all the guys came back from college. We set off balloons. It wasn’t a morbid event. It was beautiful.”

Shazier couldn’t make it back for the memorial because of his OSU commitments. He vowed to do something to honor his friend and settled on wearing Curtis’ No. 48 for a big game. He originally wanted to do it for the Nebraska game in prime time, but that didn’t work out for reasons Shazier wasn’t sure about.

The Penn State game would suffice just fine.

As difficult as it had been for Ohio State to endure the tattoo- and-memorabilia scandal that cost the Buckeyes their coach and brought stiff NCAA sanctions, it paled compared to the unprecedented situation that had unfolded in State College, Pennsylvania, over the previous year. The sexual-abuse scandal involving former defensive coordinator Jerry Sandusky was so horrific in scale that it ranks among the worst in college history. Iconic coach Joe Paterno was fired. So were the university president and athletics director. The NCAA imposed harsh sanctions that included a four-year bowl ban and allowed Penn State’s players to transfer without having to sit out a year. Many players did leave, including star running back Silas Redd to Southern Cal. The most costly might have been the departure of kicker Anthony Fera to Texas because the Nittany Lions had no capable backup.

After several high-profile coaching candidates turned down Penn State—Meyer was rumored to be among them but would neither confirm nor deny it—the school hired longtime NFL assistant coach Bill O’Brien. Much like Meyer did when he took over in Columbus, O’Brien had no tolerance for excuses because of the NCAA sanctions.

The sense of doom surrounding the program seemed justified when Penn State lost its first two games. Ohio University defeated the Nittany Lions 24–14 in the opener, though that wasn’t a major upset considering that the Bobcats were expected to have a strong team. But the next week’s loss to Virginia, 17–16, was particularly disheartening because Fera’s replacement, Sam Ficken, missed four field goals. The last one came on the game’s final play from 42 yards out.

Penn State rebounded against weak competition by beating Navy, Temple, and Illinois. Its first significant win came against Northwestern. Trailing 28–17 entering the fourth quarter, Penn State scored 22 unanswered points for a 39–28 victory. A 38–14 victory at Iowa set up a showdown with the Buckeyes for first place in the Leaders Division. Though neither Ohio State nor Penn State could represent the division in the Big Ten Championship Game, the divisional winner would officially be recognized as such.

This would be Penn State’s de facto bowl game. Appropriate for the circumstance, kickoff was at 5:30, more prominent than an afternoon start but not quite prime time, either. This would be the Nittany Lions’ biggest home game of the season, and they treated it as such. Seemingly every Penn State fan wore white, and the pom-poms created a stunning whiteout effect.

“That was probably the best stadium I’d ever been in,” Braxton Miller said.

“The atmosphere was awesome,” Ohio State center Corey Linsley said. “That had been my dream forever—to play a night game at Penn State. Everybody was pumped up. We knew Penn State was probably the best team we’d play all year.”

No one was more pumped up than Shazier. As he put on the No. 48 jersey instead of his customary No. 10, memories of his friend rushed back.

“I looked in the mirror and started shaking my head, like he’s gone but he’s with me now and I know he’s going to take care of me through the game,” Shazier said. “I used him and used the Lord to carry me through the game. I did everything I could for him. It was like I know I’m going to have a big game if I do it for Gary. I wanted to do it for him on that stage.”

****

Neither team could muster much offense for most of the first half. Ohio State punted on its first six possessions. Miller was particularly ineffective passing. After escaping serious injury against Purdue, Miller practiced all week with only minimal limitations. But in his desire to show that he was fine, he was over-amped. He completed only three of his first 11 passes and some of them were serious misfires. Philly Brown got open deep on one play, but Miller didn’t put enough air under the ball and it sailed over the receiver. Another pass should have been an interception for a touchdown. Fortunately for the Buckeyes, Penn State safety Stephen Obeng-Agyapong dropped it.

The Nittany Lions drove to the Ohio State 25, where they faced a fourth-and-12. Lacking confidence in Ficken, Penn State went for it. Zach Boren sniffed the play out and made the tackle after an eight-yard gain. The former fullback was settling in at his new position and providing needed stability for the defense overall.

“I would say the Penn State game was the first game I really understood the defense,” Boren said.

Still, Ohio State was pinned deep inside its own territory, and its offense was still stuck in neutral. Then came the game’s first big play, which resulted from an old bugaboo for Ohio State—a blocked punt. Two linemen blocked the same guy, allowing Mike Hull to race in untouched. Ben Buchanan appeared to take an extra little stutter-step, and Hull blocked the punt easily. Michael Yancich recovered the ball in the end zone to give Penn State a 7–0 lead, sending the Beaver Stadium crowd into a frenzy.

It would prove temporary. Just as it had against Purdue, the momentum turned on a penalty. Ohio State was forced to punt but retained possession when Penn State’s Brad Bars was called for holding long-snapper Bryce Haynes. Such an infraction against a long-snapper is rare, but Haynes had hustled to make the tackle on the Buckeyes’ first punt. Perhaps the Nittany Lions were deter- mined to make sure that didn’t happen again and were overzealous in hemming him in at the line of scrimmage. Given new life on the drive, the Buckeyes kicked into gear. Rod Smith ran for 12 yards. Carlos Hyde gained three on third-and-two. Miller then broke his first big run of the game, a 33-yarder to the Penn State 6. Three plays later, Hyde plowed in from the 1 to tie the score with 34 seconds left before halftime.

At a friend’s house in Florida, Pat Curtis and her family were watching. Pat is from Akron. She and her relatives remained Buck- eyes fans, and they cherished seeing Shazier wearing Gary’s No. 48. What happened at the start of the third quarter would send them into a tizzy. Penn State got the kickoff. After a short gain on the first snap, Nittany Lions’ quarterback Matt McGloin dropped back to pass on second down. As he scanned the field, Shazier blitzed up the middle. McGloin never had a chance. Shazier swallowed him up for a nine-yard loss to the Penn State 8.

“Coach had called an inside blitz,” Shazier said. “The main reason it opened up was because Zach Boren had played with the blocker a little bit and then bailed out. I got skinny through the gap and shot the gap.”

That was only the prelude. On third-and-13, McGloin scanned the field before throwing over the middle. Shazier was waiting.

“We were playing zone,” he said. “I didn’t have anybody in my area, and I read the quarterback’s eyes. I looked around to see if anyone was there and checked back on the quarterback. He threw the ball and I jumped the route.” Shazier caught the ball at the 17 and ran untouched into the end zone.

“We were at the friend’s house, and everyone was screaming,” Pat Curtis said. “I was like, ‘Shut up! I can’t hear!’ They were so excited.”

After he scored, Shazier’s thoughts turned to his friend.

“I thought, This is crazy, the way he’s watching over me, carrying me through this game,” said Shazier, who would earn co–Big Ten Defensive Player of the Week honors. “Once I scored, I was, ‘Gary, thank you,’ and, ‘Jesus, thank you.’ I wouldn’t have gotten any of this if it wasn’t for them.”

Shazier’s touchdown continued a remarkable streak by the Buck- eyes’ defense against Penn State. His score was the ninth time since 2001 that Ohio State had returned an interception for a touch- down against the Nittany Lions.

Penn State had a chance to tie the game when McGloin threw to Brandon Moseby-Felder along the left sideline. Moseby-Felder zigged through the Ohio State secondary and appeared to have a path to the end zone. But Bradley Roby made a diving tackle at the 4 after a 42-yard reception. A holding call then pushed the Nittany Lions back, and they had to settle for a 27-yard field goal. Ohio State still led 14–10.

Penn State got back in business when Miller’s deep pass on third- and-five was intercepted at the Ohio State 44. But a Nathan Williams sack forced Penn State into fourth-and-nine. The Buckeyes planned a punt-block when a player with one of the most famous surnames in Ohio State history made the biggest play of his career.

Adam Griffin, the son of two-time Heisman Trophy winner Archie Griffin, was a redshirt sophomore backup cornerback. Lightly recruited, Griffin was offered a surprise scholarship by Jim Tressel. Adam carried what could have been a tough legacy to uphold with grace. His teammates called him “Young Arch.” He didn’t mind. Even Urban Meyer would refer to him as “Archie” without realizing it. What did bother Griffin was his lack of playing time early in his career.

“It was extremely frustrating,” he said. “I remember going home at night mad at the world almost every day after practice.”

In 2012, he worked his way into being a regular on special teams. On this Penn State punt, his job was to prevent a Nittany Lions blocker from hitting Corey “Pittsburgh” Brown so that Brown could try to block the kick. But when the blocker, Derek Day, made no attempt to block Brown, Griffin’s instincts took over.

“As soon as he free-released down the field, I thought, Oh man, they’re faking this,” Griffin said.

He turned and sprinted backward. Punter Alex Butterworth threw to Day—Mike Hull was more open a few yards farther downfield—and Griffin broke it up. Ohio State took over at its own 43. From that point, the Buckeyes’ offense rolled. Miller had a pair of 13-yard completions to Evan Spencer. Carlos Hyde ran twice for eight yards to get the ball to the 1.

Miller then made as spectacular a one-yard touchdown run as could be imagined. He was supposed to hand the ball off to Hyde. But when defensive end Sean Stanley broke through the line and drilled Hyde in the backfield, Miller pulled the ball back from his running back. Miller was now forced to improvise. Somehow, he sensed outside linebacker Gerald Hodges coming from the opposite side, closing in for a blindside hit. But as Hodges dived at Miller, the quarterback did a most unnatural thing. He stepped backward. Hodges tackled air. Meanwhile, star linebacker Michael Mauti had a shot at Miller until Reid Fragel pushed him in the back and out of the play. Miller now had a path to the end zone, but it would close quickly. Safety Malcolm Willis dived at Miller, who contorted his body to miss him and hurtled into the end zone to put Ohio State ahead 21–10.

Miller is not often impressed by his own moves, but that would be one he would savor.

“That was crazy,” he said. “It shocked me, just rewinding the play, like, ‘That’s pretty sweet.’”

The crowd fell silent, in disbelief at what it had just seen. The pom-poms could be put away for good. The Buckeyes’ defense got a three-and-out, and the Buckeyes went 58 yards—28 on a Rod Smith run—to take a 28–10 lead.

Penn State scored with 10 minutes left on an 80-yard drive to make it 28–16. The Buckeyes then applied the kill shot when Miller connected with Jake Stoneburner on a perfectly thrown seam pass. Stoneburner did the rest, outrunning two Penn State pursuers for a 72-yard touchdown. For Stoneburner, it was a just reward in a season that provided plenty of tests. He’d endured the embarrassment of the summer incident with Mewhort that temporarily cost him his scholarship. He figured to be a major factor in the revamped passing game but went three games—UAB through Nebraska—without catching a pass. Even his position was changed, technically, when he became designated a wide receiver rather than a tight end. At one point, Meyer felt compelled to have a heart-to-heart with Stoneburner to light a fire under him. Meyer liked Stoneburner and respected his intelligence, but also thought he’d underachieved.

“He’s a guy that I don’t know how many times he’s been told the truth about football,” Meyer said. “He’s been one of those guys, ‘Well, Braxton didn’t get me the ball enough. They didn’t use me enough.’ Our answer was, ‘No, you don’t play hard enough.’ We showed him video of it.”

That meeting marked a turning point. After Zach Boren switched to defense, the Buckeyes needed someone to pick up some of the slack as a blocker. Though he’d always been more of a pass-catcher than a blocker, Stoneburner embraced the challenge and became effective in that role. Against Penn State, with that touchdown catch, he showed his receiving skills were still intact, as well.

Penn State would add a late touchdown to make the final score a respectable 35–23. No one was fooled. Ohio State had dominated. The Buckeyes had scored touchdowns on four of five possessions when the game was in doubt. Miller had run for 134 yards and two scores in 25 carries. Hyde had pedestrian stats—22 carries for 55 yards—but video review would reveal that 91 percent of his yards came after contact.

Penn State gained 163 of their 359 yards on their final two possessions after the outcome was secure. Ohio State did not allow a run longer than nine yards. The Buckeyes coaches’ decision to employ a more aggressive approach paid off. Ohio State had four sacks, two by Shazier. Cornerback Bradley Roby had seven pass break-ups.

During the spring, Meyer explained his philosophy of the ingredients necessary for a special season. Superior talent alone could get a team seven or eight wins. To get nine required strong discipline. Extraordinary leadership was needed for 10 or more. A reporter reminded Meyer of his pronouncement the Monday after the Penn State game. With three games left, the Buckeyes already had nine wins. But Meyer didn’t need to wait for any more games to declare that his Buckeyes had passed a threshold.

“This is a special team,” he said. “They’re fighting for each other. It’s a refuse-to-lose type atmosphere. Some of us have seen teams that play really well, and they’re blowing teams out all the time. We’re not that type of team. I can give you 150 reasons why. However, we’re a bunch of guys who work really hard, [have a] blue-collar approach, who show up every Tuesday and want to get better. You don’t want anything else as a coach.”

Excerpted by permission from Buckeye Rebirth: Urban Meyer, an Inspired Team, and A New Era at Ohio State by Bill Rabinowitz. Copyright ©2013 by The Columbus Dispatch. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. You can follow Bill Rabinowitz on Twitter: @brdispatch