Ohio is known for great football in all corners of the state. Stemming from those great programs are even better coaches, leading Eleven Warriors to investigate how these great leaders are remembered in their respective hometowns.

EAST LIVERPOOL, Ohio — There is a stone wall at the corner of West Fifth Street and Market Street in East Liverpool, Ohio, that sticks out amid the classic architecture present in the surrounding blocks of a legendary football coach's hometown.

It's got a rustic feel to it — odd, even. There are other stone walls visible in this town of fewer than 12,000, but none as prominent as the one on this corner. This one, you see, has history.

"That was the teen hangout. Today, Sheetz stores are teen hangouts. Well, in those days, this was Route 30 right here, the Lincoln Highway," Frank "Digger" Dawson said, his mouth full of Veggie Burger and finger pointing out a window from the town Hot Dog Shoppe two blocks away. "Everybody would get together on Saturday nights and watch the caravans, the gypsies, the circuses moving from town to town."

"A guy like Holtz, Hayes, they don't want to hear about all this whole 'my daughter had chicken pox, I gotta take the dog to the vet,' all this. Woody would sit, and Lou would sit and just ask question after question. Because they care about people."– Frank "Digger" Dawson

It was that hangout spot that Dawson, 80, met who many believe to be his best friend, Lou Holtz.

"You'd have to ask Lou that," Dawson quipped, before wiping ketchup from his mouth. "He was young, but his Uncle Lou was more 'in.' I was older than him, in high school. But we'd stand up there on Saturday nights."

"Uncle Lou" is the man who raised the famed coach after his biological father was called to military service in World War II, but Dawson's relationship with the coach began during their formative years and blossomed through a mutual love of football.

"He's a sophomore, I'm a senior. We're two years apart," Dawson said, recalling when the high school football team — the Potters — would head to camp at Baldwin Wallace before the season. "So we're doing the ole weigh-in, I was like a manager/trainer/anything (head coach) Wade Watts wanted — to his death, I did it. I even wrote his obituary.

"I'm weighing the players and Lou's standing in line and he says, 'I'm standing in line all this time and if I don't weigh 100 pounds I'm going to be sick!'" Dawson said, the last bit perfectly impersonating the lovable lisp the bespectacled former coach still has today. "He made like 102 pounds. He got the crap beat out of him all throughout high school."

Never known for his prowess on the field as a player — he went to Kent State and hardly saw time as an undersized linebacker — Holtz is remembered by many for the 1988 National Championship at Notre Dame, a pair of Coach of the Year Awards and recently his work with ESPN as a college football analyst.

Back home, though, he's idolized as the namesake member in the Lou Holtz Upper Ohio Valley Hall of Fame.

"We have the Lifetime Achievement, we have the Distinguished Americans, we have the regular inductees who are from the Valley and then we have the families," Dawson said. "So sooner or later somebody fits into it somewhere."

In large part, Lou Holtz owes his head coaching career to Ohio State legend Woody Hayes.

After graduating from Kent State in 1959, Holtz earned his master's degree the next year as a graduate assistant at Iowa. He then went east to William & Mary, Connecticut and South Carolina as an assistant coach, before catching on with Hayes in Columbus in 1968 — the same year the Buckeyes went 10-0 and won the national title.

"They went undefeated, won the Rose Bowl then he called Woody and says, 'I need to see you,'" Dawson said. "Woody says, 'I know you're gonna leave! You're gonna leave!' That's when he got to William & Mary. He said, 'I can't stop you. But before you leave, I'm writing a book and you're writing the chapter on defensive backfield.'

"So Lou wrote the chapter and he's ready to leave for Williamsburg and he goes over there. 'Coach, I came to say goodbye. Here's the chapter,'" Dawson said. "Woody opens up his checkbook and writes a check to Lou. Lou says, 'I can't take that, after all you've done for me.' He says, 'You take it!'"

Hayes' intensity is well-documented, ultimately leading to his demise at Ohio State with a fateful punch he threw in the 1978 Gator Bowl against Clemson. Holtz learned plenty from Hayes during that lone season in Columbus, including his own form of intensity and hard work that led to a successful coaching career.

Holtz finished 249-132-7 in 33 seasons as a college head coach, leading the programs at William & Mary, North Carolina State, Arkansas, Minnesota and South Carolina. He even spent part of a season with the NFL's New York Jets. His best work, though, was in South Bend, Ind., leading the Fighting Irish to 100 wins from 1986-96.

That's why Dawson and his crew thought it best to make the five-hour trek west to Notre Dame to gather the memorabilia Holtz had gathered throughout his steady and supremely successful coaching career. Holtz wanted no part of it coming back home to East Liverpool to be recognized — unless others from the Upper Ohio Valley were also honored.

"When he finally agreed, we went to Notre Dame (in 1997) with five vans and a pickup," Dawson said. "We put the golf cart in the pickup, but it was a haul."

The golf cart is front and center when you enter the inner doors of the museum, taking its rightful place as the vehicle of travel for Holtz when he coached Notre Dame.

"The story was, he used that cart and drove around Jerome Bettis after a practice to explain to him why he had to wear black cleats during practice," Director of Development Rosemary Mackall said. "He always wore white cleats, but Lou told him 'Now, you can wear the white cleats during games, but during practice you need to wear black cleats like everyone else.'"

Bettis, who rushed for more than 1,900 yards and 27 touchdowns for Holtz at Notre Dame from 1990-92, served as a keynote speaker during the annual Hall of Fame's induction ceremony in June. He had to — the day before it was scheduled, Holtz' Orlando mansion caught on fire.

"He saved us this year," Dawson said of Bettis' last-minute arrival.

The running back said he didn't mind doing it, according to Mackall, because of how much Holtz meant to him.

"He didn't even think twice when we called him," Mackall said of Bettis.

That's due to the love exhumed by Holtz' former players towards the coach, the same love that resonates throughout East Liverpool and is solidified at the Hall of Fame. His famous tagline "Do right. Do the best you can. Treat others the way you would like to be treated" hangs high above all else from the ceiling of the Hall of Fame.

"A guy like Holtz, Hayes, they don't want to hear about all this whole 'my daughter had chicken pox, I gotta take the dog to the vet,' all this. Woody would sit, and Lou would sit and just ask question after question," Dawson said. "Because they care about people."

Two blocks away from the Hot Dog Shoppe, past L & B Donuts, the stone wall and around the corner, a sign with Lou Holtz' smiling face and a friendly greeting indicates the entrance to the Upper Ohio Valley Hall of Fame.

"Welcome Friends & Alumni" it reads, gleaning above the doorway where a statue of Holtz resides inside once the doors lock for the evening. The statue is white and built into a removable red door, symbolizing Holtz passing through on his way to see and spend time with someone close to him.

He's canonized in his hometown only because he demanded others from the area earn the same honor — the class of 2015 includes former Buckeye and Boston Celtics legend John Havlicek, a Bridgeport, Ohio, native. Holtz believes giving back is what is most important. Not trophies, photos or plaques.

"He's said very firmly to his four kids that this will go on once he is gone," Mackall said. "He's made that very clear."

Holtz has given more than $600,000 in scholarships in the last 17 years to students selected by deans of the 24 schools in the Upper Ohio Valley area, according to Mackall. Ohio Valley College of Technology and Pittsburgh Technical Institute match Holtz' donations for education and he's also donated more than $110,000 in teacher grants. He gives back, just like he gives back vicariously through the people at the Hall of Fame, recognizing more than just sports figures from the area.

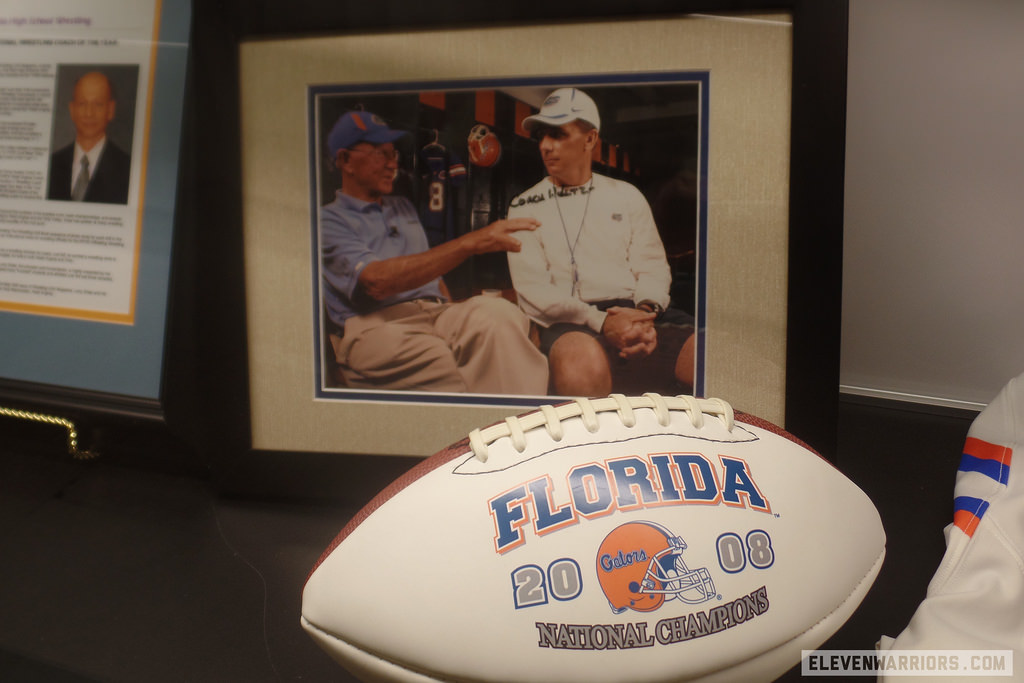

Doing so not only further christens his own tremendous legacy both in college football lore as well as his hometown, but keeps the influx of talented people from the Upper Ohio Valley in motion, too. Even current Ohio State head coach Urban Meyer is present. A photo of the two when Meyer — a 2009 Distinguished American honoree — was at Florida, sits next to a jersey and football from the 2008 national title season in a glass case.

The trinkets are there, safe from the fire that romped through his home: "He had photos with the Pope, the Reagans, the Bushes, the Clintons. All the separate administrations in the White House — gone," Dawson said. But what was lost is hardly of any consequence to the slender, amiable 78-year-old.

"Someone told me along time ago that if what you lost can be replaced, then it's not really a loss," Holtz told the Orlando Sentinel June 23. "You can't replace a parent, a spouse, a child.

"What I learned from all this is how lucky we are to have the friends and family that we have," he added.

Holtz has plenty of those, many of whom allow for his proper remembrance at the Hall of Fame that bears his name. He deserves the love, not only because of how successful he was in coaching, but also because how he gives back to the area that molded him: Ohio.

"This is where he started," Dawson said. "He comes (back) for his event. He'll pop in whenever he can. But he's always remembered here."