The 21st century could've been quite different in the Big Ten.

Just prior to the start of the new millennium, commissioner Jim Delany approached the University of Notre Dame with an invitation to join his tradition-laden league, formalizing geographic rivalries with a number of the conference's member schools. The offer was the second in five years, but the Fighting Irish alumni and trustees took the offer seriously.

According to the New York Times, however, the decision to decline yet again was still an easy one:

Last year, when the Big Ten came calling again, Notre Dame said it would study the pluses and minuses.

It did. But the student body opposed a change, and at recent basketball games there were chants of ''No Big Ten.''

Charles Lennon, the director of Notre Dame's alumni association, said that 99.5 percent of its members were against a change. University officers agreed and recommended to the 55-man board of trustees that the status quo be maintained.

At the time, the Irish were the recipients of the largest television contract in the sport, having broken ranks with the College Football Association in 1991 to negotiate their own, national deal with NBC which earned the school $7 million annually at the time. As an independent, the school also kept whatever money was earned through bowl game appearances, instead of splitting with fellow conference-members, meaning the Irish earned far more than the $2.7 million in annual handouts each Big Ten school received at the time.

The reason for Delaney's interest appeared to be his desire for a conference championship game, as the NCAA required 12 teams for a league to split into divisions as the SEC and Big 12 had recently done. The game would earn even more television revenue for the additional contest and having added Penn State in 1993, the league was just one team away at the time; a gap that would remain unfilled until Nebraska accepted the conference's offer a decade later.

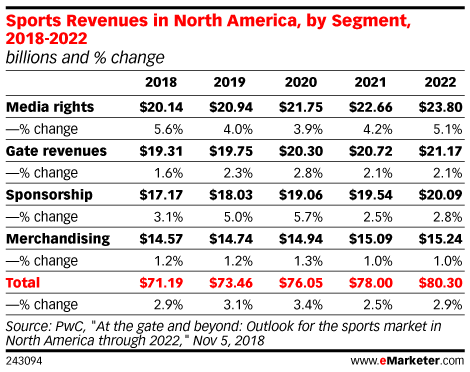

In the time since, however, the economics of college sports has changed. With the adoption of digital video recording, live sporting events became far more valuable, meaning the Big Ten's volume of events quickly became an untapped strength.

Delaney and the league vaulted its member schools into another stratosphere financially with the launch of the Big Ten Network in 2007. Last year, Big Ten schools each took home $54 million in revenue from the league, buoyed by BTN revenues, deals with Fox, ESPN, and CBS, and a $66 million share from the College Football Playoff (despite a conference member failing to earn a spot in the final four).

Initially, it appears as though the Irish have been left behind by this rights bonanza. The university makes just $3.19 annually from the CFP regardless of its participation in the event, while its NBC deal has expanded to just $15 million each year.

Additionally, the Irish have remained independent only in football, first joining the Big East in 1995 for all other sports before jumping ship for the ACC in 2013. As part of that deal, the Irish compete in five non-conference football matchups with ACC schools each season, but the returns are minuscule in comparison to Big Ten rights revenues.

ACC distributed an average of about $29.5 million to its 14 schools other than Notre Dame, which received $7.9 million. This means ACC's per-school distributions, per conferences' tax records, were basically equal to the Pac-12's

— Steve Berkowitz (@ByBerkowitz) May 24, 2019

But according to a 2018 review of Department of Education reports, The Business Journals found that the University of Notre Dame's profits were on par with the likes of Ohio State and Michigan, taking in $89 million of operating profits from football alone in 2017.

Both sides feel as though they've come out ahead in the past two decades. The Big Ten has expanded its footprint both east and west, most notably forcing cable carriers along the east coast to carry BTN thanks to the additions of Rutgers and Maryland, allowing it to remain the most profitable entity in college sports.

Meanwhile, Notre Dame has maintained its own unique tradition.

Most Big Ten schools are large, public research universities meant to educate tens of thousands each year, yet ND resembles Northwestern far more than Nebraska, with an undergraduate enrollment of around 8,500 at the private school. As such, the vast majority of Fighting Irish fans fall outside of alumni association requirements, with many having never set foot in South Bend.

As much as Big Ten fans may not want to admit it, the Irish football program has been nearly as successful on the field as off it. Since 2000, Notre Dame has performed far better than Nebraska, Maryland, or Rutgers, resembling (and in many ways outperforming) the pack of teams consistently challenging Ohio State for conference titles.

In the 20 seasons since 2000, the Buckeyes have consistently found itself top the conference standings, winning at least a share of 10 league titles. Michigan, Michigan State, Penn State, and Wisconsin have all won three each, creating a clear second tier of competition.

Despite suffering four losing seasons in that span, the Fighting Irish have still maintained a standard on par with each of those programs, even earning a spot in the 2012 BCS championship and becoming the only midwest program outside of Columbus to play for a national title.

While many criticize the Fighting Irish for feasting on service academies to fatten up win totals, their strength-of-schedule was consistently higher than that of Big Ten teams according to SportsReference.com.

| Team | Wins | Losses | Win % | Avg. Strength of Schedule Rating (0 = Average) | Final AP Poll Top-10 Finishes | BCS/NY6 Bowl Appearances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ohio State | 219 | 43 | 84% | 4.05 | 15 | 15 |

| Wisconsin | 188 | 77 | 71% | 2.78 | 4 | 6 |

| Michigan | 166 | 87 | 66% | 4.50 | 3 | 6 |

| Penn State | 164 | 88 | 65% | 3.33 | 6 | 5 |

| Notre Dame | 162 | 89 | 65% | 5.23 | 3 | 6 |

| Nebraska | 159 | 98 | 62% | 3.46 | 2 | 1 |

| Michigan State | 152 | 102 | 60% | 3.47 | 3 | 3 |

Although the Buckeyes remain the gold standard for Big Ten success, the Irish clearly belong amongst the likes of Michigan, Penn State, and Wisconsin, and have out-performed Nebraska and Michigan State despite playing a tougher schedule.

Specifically, with the dividing line for the conference running through the state of Indiana, the concept of placing Notre Dame in the Big Ten West is compelling. Despite being a former blueblood program themselves, the Huskers have failed to find much success since joining the conference, reaching just one conference title game in 2012 and bottoming out after the firing of Bo Pelini in 2014.

For Buckeye fans, this argument may be semantic, as the scarlet and gray have proven superior to the Irish on multiple occasions this century. But had the Irish joined the conference for Y2K, it may have actually helped the Buckeyes compete for even more national titles.

Over the past two decades, a not-so-quiet rivalry has sprouted between fans of the SEC, Big Ten, and every other conference, turning 'conference pride' into a regional chest-pounding contest that celebrates winning-by-association. Buckeye fans have largely avoided such outward shows of affection for hated rivals, but have struggled to avoid these larger, national conversations.

While much of the discourse takes place online, it does play a factor when it comes to rankings. The SEC is typically considered the deepest and most competitive league in the sport, earning its teams the benefit of the doubt when it comes to selecting playoff participants.

In 2017, Alabama earned a spot in the playoff despite failing to win the SEC, while the undefeated Irish themselves took one of the spots a year later. Both times, the Buckeyes were left as the odd team out despite winning the Big Ten. Replacing Nebraska with Notre Dame would've certainly helped the Buckeyes' resume in both instances.

Looking ahead, the future of conference expansion and realignment remains unclear. Economic realities may reshape the face of college sports as we know it, with costs continuing to rise and attendance declining.

TV rights deals remain equally unclear. Delaney's goal of forcing more cable companies to carry the Big Ten Network feels more and more antiquated by the day, as more and more viewers cut the cord and opt for a la carte entertainment packages. Big Ten alumni and general sports fans, regardless of location, can now easily opt for the packages and networks they want, meaning the quality of BTN programming and its access on-the-go is now more important than simple access in one's living room.

The conversation on how sports (and media in general) will be consumed in the future is a long one and something to be tackled another day. However, it's certainly one that new Big Ten commissioner Kevin Warren is considering as he looks ahead.

“You think about where we are in college athletics. You think about what the next five to 10 to 15 years look like,” Warren said in his introductory press conference last June. “When I accepted this job, I didn’t look at it as this is a today job. I looked at it as a long-term job.”

While both the Big Ten and Notre Dame both signed new deals with their respective rights-carriers in the past few years, it's quite possible that the conference's 1999 invitation won't be its last. The addition of a program that often finds itself in the top 20 top in football and men's basketball, along with one of the best women's basketball programs and a national fanbase, would certainly be an attractive addition for the Big Ten moving forward.