This week, we return to Napoleon and his battles, leaving the Peninsula behind for the time being. Borodino, as we shall see, continues the trend from Wagram- an increased ability of Napoleon’s opponents to handle his tactics and methods, and his increased reliance on mass and assault, over maneuver, to try and carry the day.

If you like military history, feel free to discuss the battle below, and to check out the archive here.

Russia breaks with France

The Continental System was designed to force Britain to heel by denying them the trading markets of Europe. However, this didn’t work out the way Napoleon thought it would. British traders still had, largely, the run of the world. The industrialization, in Britain, of textile manufacture had led to a boom in Britain, and while it would have been nice to sell cheap cloth in Europe, it turns out there were markets in the Americas, India and Africa who needed cheap cloth, and were more than happy to sell Britain a variety of goods in order to raise the money to buy cloth.

Furthermore, the Continental System made it even easier for Britain to increase its share of trade across the world. Since the French and Dutch had been at war with Britain for nearly a decade at this point, the Royal Navy had blockaded their harbors and destroyed their trading vessels for that long. Merchants and markets around the world didn’t go away. British traders and sailors stepped in to replace the French and Dutch, making even more money in the process. However, those on the Continent were cut off from world trade, and had only their internal markets to support their economies. Without access to trade, these economies began to grind down into a deep depression, leading to discontent, lower tax revenues, and a variety of other problems.

This discontent meant that most members of the System were highly reluctant members. Sweden, in particular, only pretended to go along with the System, and happily sold Britain all the timber and naval stores they wanted, so long as everyone pretended it didn’t happen (other than for tax purposes, of course.) Ultimately, Napoleon relied on the Grand Moff Tarkin strategy to keep the powers of Europe in line- fear of the Grande Armee and an even more punishing peace than before overcame, for the time being, the poor economic and financial state of these states, and they were able to limp along on the unified Continental market for a bit longer.

One power that was not, however, was Russia. Laying on the periphery of Europe, Russian merchants needed to move their goods on the Baltic and Black Seas, where the British lay in wait. (At least in theory- while technically at war, Britain and Russian relations rode a roller coaster between Tilsit and 1812, and the Royal Navy may have been reluctant to aggrieve the Russians.) Russia had, also, traditionally traded a lot with Britain and was particularly hard hit by the embargo- so much so that the Russians quietly resumed trade after the Swedish War.

Relations between Tsar Alexander and Napoleon, on a personal level, had declined a great deal since Tilsit, as well. Alexander disliked Napoleon, but was willing to work with him when there was something to gain for Russia- not fighting Napoleon, taking Finland from Sweden, gaining breathing room to deal with yet another Ottoman war. However, by 1810 or so, those issues had been largely resolved, and Alexander had gained nothing from the 1809 campaign. In addition to shifting diplomatic advantages, Alexander and Napoleon had a personal falling out over Napoleon’s marriage to Maria Louisa. Napoleon had originally approached Alexander for the hand of his sister, but the Dowager Tsarina refused to allow her daughter to marry a commoner. The announcement of Napoleon’s engagement to the Hapsburgs made Alexander think that Napoleon hadn’t been serious about his sister. Napoleon further insulted him later in 1810 by deposing the Duke of Oldenburg, the Tsar’s uncle. Both of these incidents were spun in Russia as severe insults to the Tsar’s honor and the honor of Russia. At the end of 1810, Russia formally left the Continental System.

A year of diplomatic negotiation ensued. The French plied Russia with a series of the threats, while beginning the process of mobilizing the resources and men needed to make those threats real. Russia prepared, too. Russian diplomats secured an alliance with Sweden, to secure that border, and attempted to negotiate with Britain. They also secured promises from Prussia and Austria that they would do as little as possible to support the French effort to punish Russia. The Russians also finalized the reforms to their army that they had carried out since Friedland, adopting the Corps de Armee system, increasing their reserve manpower, and building even more cannon.

On June 24th, 1812, all was in order and Napoleon was done negotiating. He’d bring the Russians to heel just as he had the Austrians in 1809.

The Russian Campaign

The army Napoleon assembled was, probably, the largest in world history up to that point. (Assuming we don’t take ancient historians at face value about the sizes of certain armies in Persia and China) 650,000 men followed Napoleon into Russia. However, only 300,000 of these men were French. Over 50,000 were Prussian and Austrian. The Austrians begged off from the march by the end of summer, and the Prussians were sent to besiege Riga, and never really helped out there. Another 300,000 came from Napoleon’s steadier allies in the Confederation of the Rhine, the Kingdoms of Italy and Naples, and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. While these governments back the campaign, the troops were considered of lower quality than the French troops- and most of the French troops were new enlistees, with fewer veterans in the French army than in 1809.

The Russians were able to mobilize about half as many men as the French at the outset, with more men coming from distant parts of the Empire or raised as local militias or units. The Russians divided their forces into three armies, two directly across from Napoleon’s army in Poland, the other further to the south to guard against a larger Austrian invasion. Overall command fell to Barclay de Tolly, the Army Minister and leading strategist of Russia.

With a million men maneuvering in the area north of the Pripyat Marshes, logistics and supply would be vital for the campaign. Both Napoleon and de Tolly realized this, and their efforts reflected this basic reality. Napoleon immediately broke his army up into several columns, to make supply and marching easier. He also broke off a large chunk of his army to head up the Baltic coast, making for St. Petersburg- taking the Russian capital would help the French cause quite a bit, as well as make that army easier to supply. As he marched he tried to keep between de Tolly’s First Army and Bagration’s Second, looking to defeat one, then the other, and achieve a rapid decision through rapid, decisive maneuvers.

De Tolly knew this situation as well as Napoleon, and his overall strategy was not to fight Napoleon at all. Instead, de Tolly decided to focus on petite guerre, where he held an advantage. A large number of Cossacks rallied to the Tsar’s standard. While not much use in a regular battle, Cossacks excelled at raiding, skirmishing, and small fights. De Tolly gathered enough supplies to feed the Russian armies, then had the Cossacks denude the countryside of crops, food and shelter for the French. While this was rather cruel treatment of his own peasants, who were left to starve and freeze, it denied the French supplies. The poor roads in Russia made it difficult to move supplies in from Poland, and all the rivers ran the wrong way to support the campaign. When the French troops left their camps to scavenge for food, Cossacks descended on them, eager for a good scrap.

Napoleon’s first move was to march on Vilnius, in an effort to drive a wedge between de Tolly and Bagration. With Davout observing Bagration, Napoleon lunged at Vilnius in a desperate series of forced marches to try and catch de Tolly. However, de Tolly kept a move ahead of Napoleon, refusing to fight the French army. Instead, Napoleon’s men exhausted themselves in skirmishes with Cossacks, hunger, and marching through unhealthy swamps in the summer, leaving thousands dead of disease without a serious battle.

While Napoleon’s maneuver to Vilnius did not get him the battle he wanted, it did separate the two Russian armies he faced. He packed up his army quickly, and marched south, hoping to pin Bagration against he Pripet Marshes. Baragration used his cavalry skillfully, using it to keep Napoleon from concentrating his army against him, and confusing Napoleon as to his whereabouts and chasing phantoms. By the end of July, Bagration had escaped Napoleon, and given enough time for de Tolley to move from Lithuania to Belorussia, closer to unifying the two armies.

With Napoleon deep in Russia, suffering from disease and a lack of supply, de Tolly decided it was time to unify the two armies in a strong defensive position and face Napoleon. He believed the fortress city of Smolensk offered the best opportunity, and so unified his armies in the walls and area around the city. On August 17th, Napoleon arrived at the city, and launched a swift bombardment of the fortifications that lit the city aflame, destroying much of the fortress. A quick assault began clearing the city, and at the end of the day, de Tolly abandoned the city in good order rather than fight out of position. De Tolly destroyed the remains of the fortress and its depot on the way out, denying Napoleon the supplies and shelter he needed.

de Tolly broke of a detachment of his army to march to relieve besieged Riga, forcing Napoleon to send St Cyr to chase it down before it got to the siege. De Tolly was able to make up the lost troops as he marched back towards Moscow, Napoleon was not. However, de Tolly’s retreat from Smolensk, and refusal to fight Napoleon, had led to discontent in the Tsar’s court. Nobles that had had their peasants abused by de Tolly’s Cossacks and Napoleon’s troops protested. The willingness of de Tolly to cede their lands to the French also raised anger a court, and some event went so far of accusing de Tolly of cowardice and even collusion with the French. This led to his ouster as overall commander by Alexander on the road back to Moscow, replaced by Mikhail Kutusov. While Kutusov had orders to fight Napoleon, he largely kept to de Tolly’s strategy until Semptember.

70 miles from Moscow, Kutusov found his spot by the town of Borodino. The area offered commanding heights, open but difficult terrain, and a variety of rivers and streams to deal with. A good ways ahead of the French, Kutusov began to dig in.

The Battle of Borodino

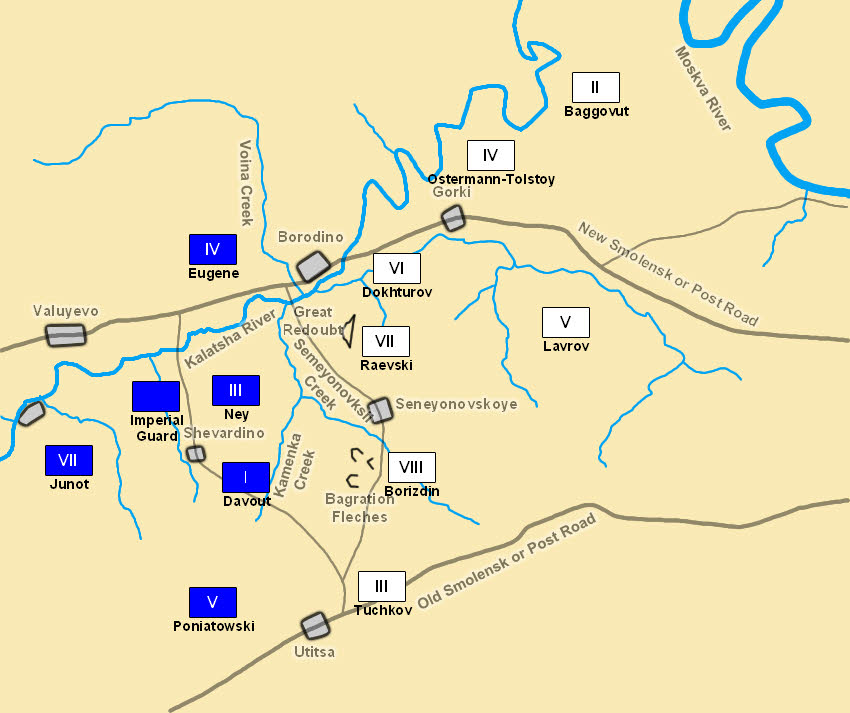

Kutusov’s deployment around Borodino has come under a lot of rather valid criticism. He deployed de Tolly’s First Army along to the north, using the Kalatsha River as an obstacle to French advance, while anchoring his army on a series of field fortifications known as the Fleches. This left the Old Smolensk Road open, and Napoleon could have marched right down it on September 5th, when he arrived in the area of the battlefield. Realizing this, Bagration, who commanded the southern 2nd Army, began redeploying his forces to the south, but needed time. He reinforced a forward fortification, the Schevardino Redoubt, forcing the French to stop the their advance on the 5th, and storm the fort. The Russians delayed all day, and then retreated in the night, their lines along Borodino secure from the Smolensk Road to the north. The center was well fortified, with the Fleches on one hill, the Grand Redoubt to the north, and Borodino itself fortified as well.

With the Kalatsha River blocking his ability to attack the northen wing of the Russian army, Napoleon decided to go for the center- the Great Redoubt, the Fleches, and, if possible, a turning maneuver around the Old Smolensk Road. At this point, Napoleon was down to about 150,000 men under his direct command in the area, with most of the rest of the army scattered around Russia, while he faced an army of about equal size. However, both sizes had enormous numbers of artillery- the French around 550 guns, the Russians about 650. However, over 300 Russian guns were deployed to the north, away from the main action, while Napoleon concentrated his in the area of his attack. Both sides spent September 6th preparing, with the fighting to come on the 7th.

Napoleon’s plan was not particularly complex. Prince Eugene’s Corps would attack Borodino itself. Junot and Davout would attack the Fleches and the gap between the Fleches and the Great Redoubt. Poniatowski’s Corps would make an attack against the southern Russian flank, and attempt to turn it. (Why Napoleon would send his best commander and corps into a frontal attack rather than send Davout on the flank march is still a mystery today.) The battle opened at 0600 with a massive artillery bombardment. Napoleon formed a battery of over 100 guns to pound the Russian center, while Russian artillery along the front responded. At about 0630, Euguene made his attack on Borodino, which de Tolly had little intention of seriously holding. About 0700, Davout launched his assault on the Fleches. By 0730, Eugene had cleared the town and began and advance on the Redoubt, while Davout cleared the Fleches.

This led to an immediate response from Bagration. He launched two counterattacks, driving Eugene back into Borodino, and called for reinforcements from Kutusov as he launched a second counterattack against the Fleches, driving the exhausted and disorganized attackers out of the the position Kutusov peeled men off the northern flank to reinforce Bagration, rushing to beat the reinforcements coming to support Davout. At about 0930, Ney and Jonout’s Corps reached the Fleches and began a massive back and forth battle for them. Literally, no one knows exactly what happened in the fighting, Men and guns piled into the positions from both armies, and from all angles. Murat, leading a cavalry charge, was nearly captured. Ney was wounded and had to retire from the day. Bagration suffered a mortal wound, and had to be carried from the field only to die two weeks later. At about the same time Poniatowski launched his attack against the Russian southern flank. More Russian reinforcements from the north rushed down to defend the area, forcing a bloody stalemate.

By about 1030, the French had cleared the Fleches, and the Russians reformed on the heights behind them, and a lull broke out over the battle.

The lull broke at 1200. The Russian Cossack commander discovered a ford across the river, and snuck his way around the French northern flank. They descended down on the town of Borodino, raiding the French position. While they made no serious effort to take the town, the French reacted quickly to the attack. Cavalry reinforcements rushed to the area, and the attack against the Great Redoubt, planned for just after noon, wouldn’t come until 1500.

Between 1200 and 1500, 400 French cannon assembled outside the Redoubt, and began pounding it. Eugene’s Corps formed up to attack from the north, while the Second Cavalry Corps formed up to attack south of the Redoubt, then sweep in behind it to pin the Russians inside. At 1500, the assault went off, advancing under a deadly Russian fire. Fighting in the redoubt lasted for an hour before it fell, and de Tolly organized a fighting retreat to Bagration’s positions east of the Fleches. During this fighting, the French hammered the Russians with cavalry charge after cavalry charge, but the Russians held in good order as they continued their retreat. By about 1630-1700, the Russians, exhausted, reformed their line.

Meanwhile, in the south part of Junot’s Corps marched to meet Poniatowski. The two forces joined up for a well coordinated attack that began pushing the Russians back off the Smolensk Road. At about 1700, the Russians in the area organized a retreat back to their main lines, rather than get cut off.

The Russian situation was, quite simply, desperate. Their men had been fighting for almost 12 hours. There were no reserves left. Tens of thousands of men were dead or wounded. Commanders were dead or out of commission. Command in the line was disorganized and confused, with Kutusov barely aware of where his men where or who to give orders to. Napoleon still held a corps of fresh troops- his very best, the Guard Corps. At 1700 Napoleon went forward to survey the lines, and his generals urged him to commit the Guards, smash the Russian army open, and finish it.

He refused. The next day, exhausted, the Russians continued their retreat to, and passed, Moscow. They left behind unknowable carnage: about 10,000 dead French and 15,000 dead Russians. About 25,000 French were wounded, and another 30,000 Russians. However, in the bleak situation of the campaign, anyone who didn’t walk away from the battle, wounded or not, had little to no chance to survive.

On Semptember 14th, Napoleon entered Moscow. He hoped to find shelter, warm houses to appropriate, and food enough to feed his men for the winter. He arrived to find the city largely empty, and completely stripped of supplies. His men ran riot in the city, setting several fires that eventually consumed the city.

He was deep in Russia, with no food, no shelter, and winter not far away. He demanded Alexander surrender, how that Napoleon held the Russian Capital and had won Borodino.

Alexander told him to go fuck himself.