As a sophomore defensive lineman at Notre Dame in 1974, Gene Smith thought about leaving school.

His roommates and several of his other close friends, including fellow Northeast Ohio native Ross Browner, were suspended for a violation of the school’s dormitory code, and Smith was depressed. He had also broken his arm, knocking him out for the entire season, and on a predominantly white campus, he felt alone.

Smith had packed his belongings into his car and was prepared to drive home – without even telling his parents first – until Notre Dame defensive line coach Joe Yonto, having found out that Smith was planning to leave, called Smith into his office and convinced him to stay.

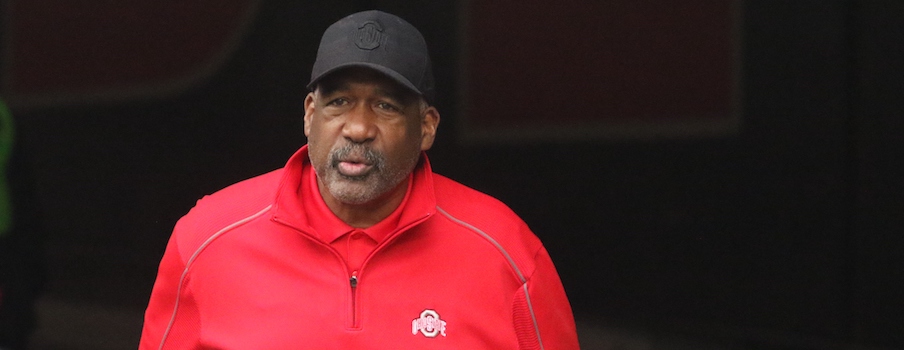

By staying in South Bend, Smith went on to graduate from Notre Dame in 1977, then spent five years on the Fighting Irish’s coaching staff, which helped set him up for his future career in athletic administration that has led to his current role at Ohio State’s athletic director. That might not have happened, though, if not for Yonto – because there wasn’t anyone else on campus who Smith felt he could talk to about how he was feeling.

“Back in the day, you just sucked it up,” Smith recalled during an interview with Eleven Warriors last fall. “If you were blessed to have somebody like I ultimately ended up with with a position coach, otherwise you just sucked it up and found your way to deal.”

Smith doesn’t want any of Ohio State’s current student-athletes to feel that way. That’s why he spearheaded an effort to expand Ohio State’s sport psychology staff, which now includes four full-time sport psychologists and athletic counselors, and has made mental health a key area of focus and regular topic of conversation within the athletic department.

The importance of mental wellness for student-athletes to be at their best both on and off the field has become nationally recognized in college athletics, but it hasn’t always been that way. It hasn’t even always been that way during Smith’s tenure at Ohio State. But in recent years, the stigma surrounding mental health has slowly started to fade and in turn, more and more student-athletes have started to open up – whether privately to counselors, to coaches and teammates or in some cases, even publicly – about issues they are dealing with.

“It’s just grown so much,” Smith said. “It’s our No. 1 issue right now. Last fall, we had two rowers who got some other athletes together, and they decided that they were gonna do a summit … and they had Urban (Meyer), Ryan Day, another female athlete (who survived) a suicide attempt … and it was organic. I don’t make many things mandatory for our athletes, because they got enough stuff going on. We had over 500 athletes in that room.

“And then I remember, someone asked, I can’t remember if it was one of the athletes asked, ‘How many of you know of somebody that may have tried to attempt suicide or did attempt suicide?’ 75 percent of the room raises their hand,” Smith recalled. “That’s unheard of, but it’s also unheard of that you would sit in a room and admit that. So it’s been a big issue nationally, it’s been a big issue for us over the last few years, and we just had to do something.”

Smith is far from the only leader in the athletic department who has embraced the growing conversation around mental health. Day, who revealed his personal struggles with mental health last summer when he and his wife launched the Christina and Ryan Day Fund for Pediatric and Adolescent Mental Wellness, regularly talks to the football team about the importance of mental wellness and lets them know it’s okay to ask for help.

“I think we all have a responsibility to make sure that people understand that part of being healthy is being mentally healthy,” Day said on a teleconference this week. “Everyone has physical health and everybody has mental health. And sometimes when you hear the term mental health, people take pause. Well, it’s just like eating well and putting good food into your body, working out physically. Having a strong and healthy mind is critically important.”

Like Smith, Day has seen the conversation around mental health evolve substantially since he was a student-athlete at the University of New Hampshire, where he was a quarterback from 1998-2001. He believes that’s partially because of the effort to destigmatize that conversation, but also because of the pressures young athletes face now – often starting at the youth sports level – that has also only increased due to higher expectations and social media.

“The social media part is something that our guys cannot get away from, and the constant pressure to uphold their image and status is something that is very hard on them, and it’s very, very important to them,” Day said. “Even though we can tell them a million times till we’re blue in the face that it doesn’t matter, it does to them, and that’s what’s going on with this generation.

“It’s a very different environment, and I think it’s created some more stress for these kids and anxiety. And we’re not gonna change it, but we have to embrace it, to figure out ways to help them.”

Historically, the stigma around mental illness – especially for men and especially in contact sports like football – has been that it’s something people can simply tough their way through. But while Day often preaches toughness to his team when talking about football, he says being mentally tough and being mentally healthy can go hand in hand, and it’s important to delineate between them.

“It’s like saying, are you physically tough or are you physically healthy? They’re two different conversations,” Day said. “You have to be tough to play this game. There’s no question you have to be tough. But if your mind’s not in a great place, boy, it’s hard to be tough.

“The old thought process of just getting through it or if you’re going through a tough time, you get off the field and you’re at home and you want to reflect on why you’re feeling a certain way, it’s okay. That’s a healthy thing. That’s part of recovery. That’s part of staying healthy. And I think they’re two different things. But in terms of being mentally tough and staying mentally tough, that’s just still a huge part of what we have to do in all sports. And trying to help find that balance is critical.”

“sometimes when you hear the term mental health, people take pause. Well, it’s just like eating well and putting good food into your body, working out physically. Having a strong and healthy mind is critically important.”– Ryan Day on mental health

Ohio State men’s basketball coach Chris Holtmann has also embraced the need to address mental health issues, as evidenced by his comments this past February after DJ Carton left the team to focus on his mental health. Holtmann, who revealed then that he sees a therapist himself, said there is “nothing more important” than his players’ health – both physical and mental – and called out the “antiquated thinking” of people who questioned Carton’s decision and the program’s support of it.

That said, Holtmann acknowledged this week that he didn’t always embrace that conversation so openly.

“Probably 15 years ago, maybe I had been reluctant to bring down mental health professionals into our locker room and around our environment. And I think I had to change my thinking 8-10 years ago,” Holtmann said.

While Carton chose to publicly disclose his mental health battle, Holtmann says he has had other players who have also faced mental health issues that they did not publicize. Specifically, Holtmann said he has “had more students come through my office and ask for help in the last five years than in the previous 15 years I was in coaching.”

“I think it’s been a 180 from when I played,” Holtmann said. “I think there very much was a stigma about it when I played and early in my coaching career, and I think so many issues that involved mental health, you just kind of gritted your teeth and got through it. And sometimes, oftentimes, that wasn’t the best approach. And I think we’ve seen a dramatic shift.”

Holtmann, like Day, believes social media has been a factor that has led to more mental health issues, especially for young people in the spotlight like college athletes.

“The amount of hours that our athletes are influenced by social media is greater than any other information influence in their life right now. It’s what they’re feeding on constantly,” Holtmann said. “I think people in general, whether they’re in a high-profile position or not, struggle with the idea of comparison in social media, but it certainly gets accelerated when you’re in a high-profile performance position like a lot of our athletes.”

Jamey Houle, Ohio State’s lead sport psychologist, has also seen the conversation around mental health evolve since his career as a Buckeye gymnast from 2001-04. He believes mental health services have become much more normalized than they were back when he was a student-athlete, and that Ohio State athletes have become more and more comfortable seeking help from him and the other staff members in Ohio State’s sport psychology department: Chelsi Day, Candice Williams and Charron Sumler.

“It’s evolved to the place where therapy is seen just as if you sprain your ankle, you go see a doc; if you’re feeling down and you’re feeling anxious, you just go see the psychologist. It’s become way more normal if you will to seek help from a sport psychologist or athletic counselor,” Houle said. “So I think it’s just gone from, ‘You got a problem, go see a sports psychologist,’ to ‘Hey, you want to take your game to the next level, you should go talk to Charron or go talk to Candice, go talk to Chelsi.’ The integration has really changed.”

The stigma around mental illness and going to counseling still exists, and breaking through that stigma remains a primary goal for Houle and his colleagues in sport psychology. But they say the support they’ve received from leaders like Day, Holtmann and Smith, both publicly and within the athletic department, has gone a long way in helping them achieve that goal and ensure that Ohio State’s athletic culture is one that promotes mental wellness.

“That advocacy is unbelievable,” Houle said. “It really opened doors for the athletes to see us as regular folks that they could talk to.”