It’s 6 a.m. on Aug. 20 last summer and Columbus hasn’t woken up yet.

Fewer than a dozen cars sit dormant in a lifeless parking lot. Darkness shrouds most everything in sight, including a sign welcoming passers-by to Columbus planted firmly in the ground out in front of a wide building fashioned a bit like a strip mall on Westerville Road. All but one of the businesses leasing space, including a death metal radio station, an African television station’s office and a moving company, still have their lights shut off.

The sole sign of activity is located in a brightly-lit room on the far right side of the facility, which sits barely a half-mile south of an Interstate 161 exit to the northeast of the city. Fading grey letters above the entryway read “Training camp.” Inside, four treadmills and six elliptical machines rest to the right of a bright red desk. A rock props the glass door at the entrance open. Nobody’s in there.

But through a second barely-ajar door in the back of the room, images flash and the unmistakable sounds of basketballs bouncing, shoes squeaking on the hardwood and rap music emanating from the speakers can be heard. It opens and there’s Malaki Branham, the 6-foot-5 shooting guard on the precipice of five-star status.

He committed to Ohio State a little less than a month before, but he hadn’t yet started his senior season at St. Vincent-St. Mary that eventually concluded with a state championship trophy and Ohio Mr. Basketball honors in the spring.

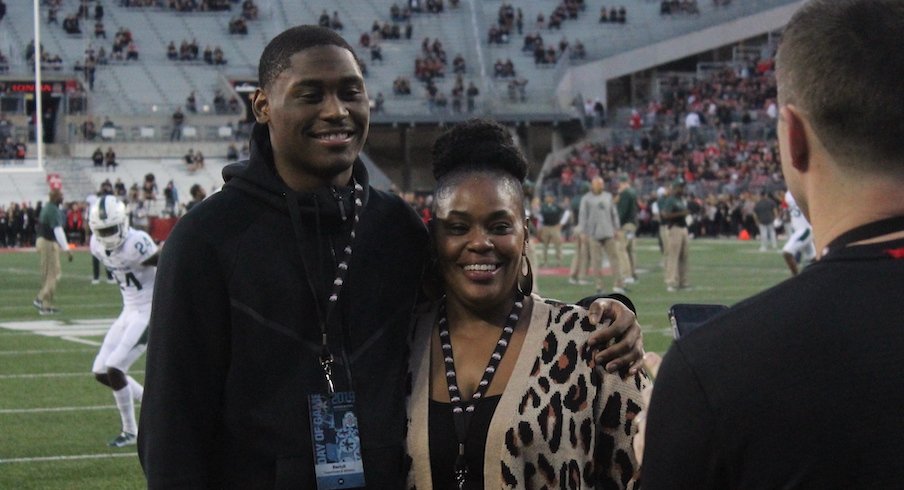

He was back in Columbus, his hometown city, to work out with Jason Dawson, the only trainer he has ever had. Four other high schoolers, including Furman-bound Tyrese Hughey, Davidson-bound Des Watson and Liberty-bound DJ Moore, are there alongside him on this Thursday morning. Only three other people are inside the nondescript facility, with one being Branham’s mother, Matia, who’s blending into the background as she quietly listens to music while using the weight machines beside the half-basketball court.

This is how Branham likes it. Quiet. Understated. No cameras capturing his every move. No social media posts. Nothing outlandish. Just him and a quartet of soon-to-be Division-I hoopers from the state he grew up in trying to get work in before dawn breaks. Similarly to his game, he’s about substance over flash.

“He's not like the ordinary 17-year-old kid,” Dawson says. “He's laid back. He's like an old-school soul. ‘I’m just going to play basketball. I just love playing basketball. I'm going to do whatever it takes to play basketball.’ He's very humble. You'll never know that he's in the gym. He’s top-25. You’d never know he's top-25 walking in the gym. He’s going to talk to you. He’s going to smile. He’s got a low cut. Just an old-school dude.”

Branham knows the drill by this point, and so do the others on the court on this day. There aren’t any explanations or questions about what to do. This isn’t their first pre-dawn workout. All have been here with Dawson before. This Thursday morning, they’re in the gym for an hour-long ball-screen workout.

Branham arrived before 6 a.m., and he’ll be back for a second workout with Dawson at 9 p.m.

“When Jason tells me to be here, I'll be here,” Branham says through his trademark toothy smile.

Dawson never asked to train Branham, and Branham never asked for Dawson to train him. Their entire relationship stemmed from the budding shooting guard’s grandmother.

When Branham was in fifth grade, his grandmother, Luzon, approached Dawson. Having just completed a professional basketball career overseas, he had returned to Columbus where he started training his nephew, who’ll be entering high school later this year. She told him that she wanted him to train her grandson as well. At the time, Branham was just hooping for fun with no long-term goals in mind. His grandmother had bigger ideas. Dawson knew of Branham from all the times he saw him at the gym at New Covenant Believers' Church, the place where he trained as a pro. But he didn’t view the then-fifth-grader as anything special.

“His grandma wanted someone to train him and nobody would train him,” Dawson said. “I was like, yeah, as long as he can guard my nephew. He was a long, gangly kid. I was like, he'll make my nephew better.”

By taking him in, Dawson’s client list doubled: Branham and his nephew.

Neither party sugarcoats their early time together. Branham, they both agree, wasn’t very good. He had more potential than most because of his frame, but he lacked skill at a young age. As Dawson put it, “he was just long” and “it was a lot of work to be done.” Initially, he couldn’t dribble either and played mostly in the post, so they worked on him becoming a “big guard.”

Even by the time dribbling wasn’t a major issue, the early scouting report of Branham was simple: Let him shoot, don't let him drive, prevent him from going to his right and make him mad.

“He's a perfectionist, so if he don't get anything right, perfect – he's still this way – then he gets upset with himself,” Dawson said. “Like, all right, he's trying to be perfect every single time. That kind of motivates him to kind of do more, do more, do more.”

That perfectionism, he says, stays with him to this day.

People who know him still tell him that when he gets down on himself on the court, it’s noticeable because he’s so often smiling. His mother says he gets that trait from her. She remembers tearing through dozens of sheets of paper trying to write something correctly, and now she’s imploring that her son understands that not everything will go according to plan. As she puts it, “If we was all perfect, then, hey, we'd all be millionaires living in mansions.” Head coach Chris Holtmann tells Branham it’s a good thing to be driven for perfection because it helps push him. but he also says that Branham has to learn to handle it in a certain way.

“When I was younger, it got bad, though,” Branham said. “I’d miss one shot and I’d be mad. When I was younger, it was horrible. It got better over the years, but it just needs to keep getting better.”

His desire to do everything perfectly never got to the point where it sidetracked Branham and made him question whether he wanted to hoop. He continuously showed up. Just about every day after school, he’d be there with Dawson.

By the time he reached seventh grade, basketball became a lot more serious to Branham. Part of that focus came from his uncle, Lawrence, who at the time left Tennessee and arrived in Ohio. Working after school with Dawson became more of a year-round thing, and they’d also have some morning and evening sessions.

Along the way, Dawson learned that challenging Branham was important – even if he had to kick him out of the gym on a couple of occasions – because more often than not, he’d respond by exceeding what was asked of him. So, when Branham told Dawson in seventh grade that he hoped to dunk in middle school, Dawson responded by saying that he had to have an in-game slam by the end of his eight-grade season at Ridgeview Middle School. If not? Branham, who Dawson says had “no bounce” when he was younger, would owe him 100 sprints.

Calf raises became a regular occurrence – 500 before a workout, 500 after a workout. He did them every day.

Most of his eighth-grade season passed without any dunks. He started to be able to do them in workouts but had yet to pull one off in live action. Then came the last game of the year. Branham remembers his team was losing with a couple minutes left when he stole the ball, ran down the court with a defender chasing him and rose off his right foot with the ball cupped in his left hand.

“When I got up, the dude jumped and I dunked on him,” Branham said. “It's my first dunk and my first body.”

Dawson responded with delight, “You didn’t have to dunk on him.”

But he did anyway.

“I knew he was going to play Division-I after he dunked on the kid in eighth grade,” Dawson said. “When I tell you to go get an in-game dunk and you find a body to go get an in-game dunk, you're going to be pretty special.”

To begin high school, Branham left Columbus for the first time, moving to Akron with his uncle where he found himself “out of my comfort zone” at St. Vincent-St. Mary High School. Initially, he found himself on the junior varsity team, which he says he certainly didn’t imagine would happen.

“After that, I was just working, working crazy to get on varsity, which I did at the end of the season,” Branham said.

The summer in between his freshman and sophomore years, he went back to Columbus to work out with Dawson, and by the time he got back to St. Vincent-St. Mary, he was ready to take off. As a Columbus native, he had long been on Ohio State’s radar, but as a 10th-grader he began to talk to Holtmann and assistant coach Ryan Pedon, who started to ramp up their pursuit.

The Buckeyes’ pursuit further ramped up when he had a breakout performance in Atlanta as part of the Nike EYBL circuit. He shot up the rankings after he went off at Bill Hensley Memorial Run ‘N Slam in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The Buckeyes didn’t waste any time, becoming the first high-major team to offer Branham a scholarship.

It was, of course, a big deal. But this wasn’t a case of a hometown kid getting an offer from a hometown school and knowing he’d end up there. Notably, he didn’t grow up an Ohio State fan. Nobody in his family did. And he had to tell that to the coaches of every other school that had interest in him because, well, they all asked the same question to make sure they weren’t wasting their time.

“I'll be honest, and I don't know if you've heard this, but we were never Ohio State fans,” his mother said. “So it's just like, ‘OK, Ohio State? Mmm. OK. It is what it is.’”

Holtmann and Pedon decidedly did not treat Branham like just another recruit, though. They prioritized him, making him their No. 1 target in the 2021 cycle. In doing so, they developed relationships with just about everybody in his vicinity.

They constantly talked to Branham, doing so to the point where he has described them jokingly as “slightly annoying.” They called his mother enough times that she’d sometimes see her phone ring and have her daughter answer it since she knew they’d be comfortable chatting with her. They got to know his grandmother, which Branham says was “kind of big for me” since she’s been an integral part of his life both on and off the court. They stayed in close contact with his uncle. They rang Dawson, who played for Holtmann at Gardner-Webb, so often that he says, “I felt like I was getting recruited too, at some point.” They knew his circle – which was essentially his uncle, mother and trainer – was small and that they couldn’t leave anything up to chance.

Ohio State wasn’t alone. Louisville came after him. So did Xavier and Baylor. Alabama, Marquette, Michigan and Illinois were pursuing him, too.

At the peak of his recruitment, Branham estimates he was spending two or three hours a day talking to coaches. Some would call him for a half-hour and others would just check in for 5-10 minutes. Ohio State's coaches called him and FaceTimed the borderline five-star recruit on almost a daily basis.

At one point, as somebody who grew up in Columbus and hasn’t lived outside of Ohio, Branham became intrigued with the possibility of getting away from home. Dawson responded with a piece of logic Branham still remembers: If he gets to the NBA, he’ll see everywhere anyway.

By calling and hosting Zoom meetings and going to his pre-pandemic games and offering first and calling some more, the Buckeyes stayed at the forefront of Branham’s mind.

“Malaki’s a loyalty kid,” Dawson said. “He’s not a kid that's going to jump from program to program. Not the kid that's going to be like, ‘Ah, yeah, well…’ You don't need to boost him. You need to love on him, and once you love on him, he's going to go through a brick wall for you. That's his thing.”

The Buckeyes learned that about Branham early and knew they had to stick with him. They wouldn’t – and couldn’t – let him get away.

And it didn’t hurt, either, that him picking Ohio State would mean he’d be in the same city as Dawson year-round for the first time since middle school.

“I'm the last part on that. Maybe the last piece,” Dawson said. “I told him wherever you want to go, I'm going to be happy. Wherever you want to go, I'm going to support you. Wherever you're going to go, I'll come visit you. But I think, for him, to continue to have that ... He likes to hear the voice. He likes to hear his uncle's voice to hold him accountable. He likes to hear my voice to hold him accountable. And then you have these coaches to hold him accountable. So I think it's just the extra voice, like I'm going to be accounted for. They can only reach me so far in this place. I think he really started thinking about that. Then again, what happened with him is he was just comfortable with the coaches. He was just comfortable. He enjoyed them. He trusted them.”

On July 22, 2020, Branham made it official. He announced his commitment to Ohio State.

That gangly fifth-grader, the one with all of the potential but none of the polish, had become the No. 34 player in the nation and the best player in Ohio, and he opted to stay home and play for the in-state Buckeyes.

“Just their plan for me,” Branham says, explaining why he picked Ohio State. “Also, I just built a great relationship with all the coaching staff, head coach, just everybody on the coaching staff. I just felt more comfortable with the coaching staff. I just felt like that was the best place for me.”

A lot has changed since that 6 a.m. workout nearly 11 months ago.

For one, he’s a Buckeye now. Branham enrolled last month and is in the midst of summer workouts with the rest of his team. He’s also the reigning Mr. Basketball in Ohio who won a state championship with St. Vincent-St. Mary in March. He just dropped 40 points in the Kingdom Summer League this past weekend. He has plans to wear the No. 22 jersey that was retired two decades ago to honor Jim Jackson.

As somebody who’s always striving for perfection, things are going about as well as Branham could have hoped. And nobody who’s closest to him would say they’re surprised.

“He hasn't reached his potential yet,” Dawson said. “The people haven't really seen him really play. They've seen him play at a high level. He played against Sierra Canyon. But they haven't seen Malaki just go. I think it's going to come out of him, this shell he's in. He's very conservative. He can come out of games chill. But once he breaks through... That's why he's working out with pros. That's why he's working out with other guys. It's like that mentality, so he can just kind of, 'All right, this is what I need to do every time when I step on campus.’”