"This started with the Cleveland Browns..."

...said Alabama head coach Nick Saban at a coaching clinic for Mississippi high school coaches in 2010, as he began a lecture on how he defends the "spread" offenses that are now taught at every level of football. The coach's point had begun by talking about where he aligns his safeties, noting that a defense is always in a better scenario to defend the pass when both safeties are lined up deep. But with the zone-read option becoming so common, defenses must be able to bring one safety closer to the line in an effort to consistently stop the run.

But instead of pointing to a successful game or scheme against a read-option team, like his dominant victory over Urban Meyer's Florida offense in the 2009 SEC championship game, the seasoned veteran of the sidelines recalled his days at the pro level. Before taking the head coaching job at Michigan State in 1995, Saban was the defensive coordinator of the Cleveland Browns, the second-in-command of a staff led by Bill Belichick that featured a number of future stars in the profession.

Any Browns fan over the age of 25 will likely remember the 1994 season, Saban's last with the team, as it is sadly the most successful season in the past three decades, seeing the Orange and Brown make their way to the second round of the playoffs before losing in Pittsburgh to the rival Steelers. That Steelers loss was the game to which Saban harkened back when discussing his modern defense:

"This started with the Cleveland Browns, I was the defensive coordinator in the early 90s and Pittsburgh would run 'Seattle' on us, four streaks. Then they would run two streaks and two out routes, what I call ‘pole’ route from 2x2. So we got to where could NOT play 3-deep zone because we rerouted the seams and played zone, and what I call “Country Cover 3” (drop to your spot reroute the seams, break on the ball). Well, when Marino is throwing it, that old break on the ball shit don’t work."

At the time, Saban and Belichick most preferred running a Cover 3 defense, which meant there were three defenders playing zones downfield. But the Steelers had consistently shredded it by running four receivers deep against those three defenders, meaning one of them would always be open. Saban continued,

"So because we could not defend this, we could not play 3 deep, so when you can’t play zone, what do you do next? You play Man (cover 1), but if their mens are better than your mens, you can’t play cover 1.

"We got to where we couldn’t run cover 1 - So now we can’t play an 8 man front.

The 1994 Browns went 13-5 , we lost to Steelers 3 times, lost 5 games total (twice in the regular season, once in the playoffs). We gave up the 5th fewest points in the history of the NFL, and lost to Steelers because we could not play 8-man fronts to stop the run because they would wear us out throwing it."

Today's spread offenses create the same problem for opposing coaches, offering numerous options in the passing game while still being able to run the ball effectively from the same formation, thanks mostly to the numerical advantage given by the threat of a running quarterback. But over time, Saban has built a hybrid system that combines the best aspects of man and zone defenses.

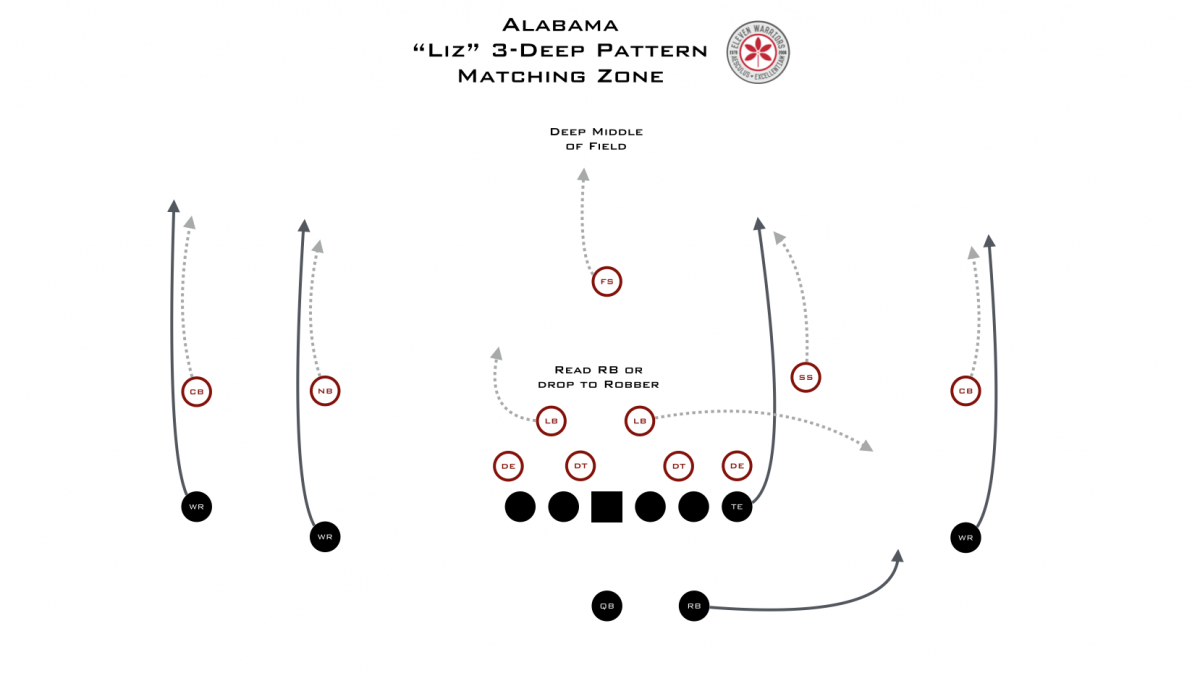

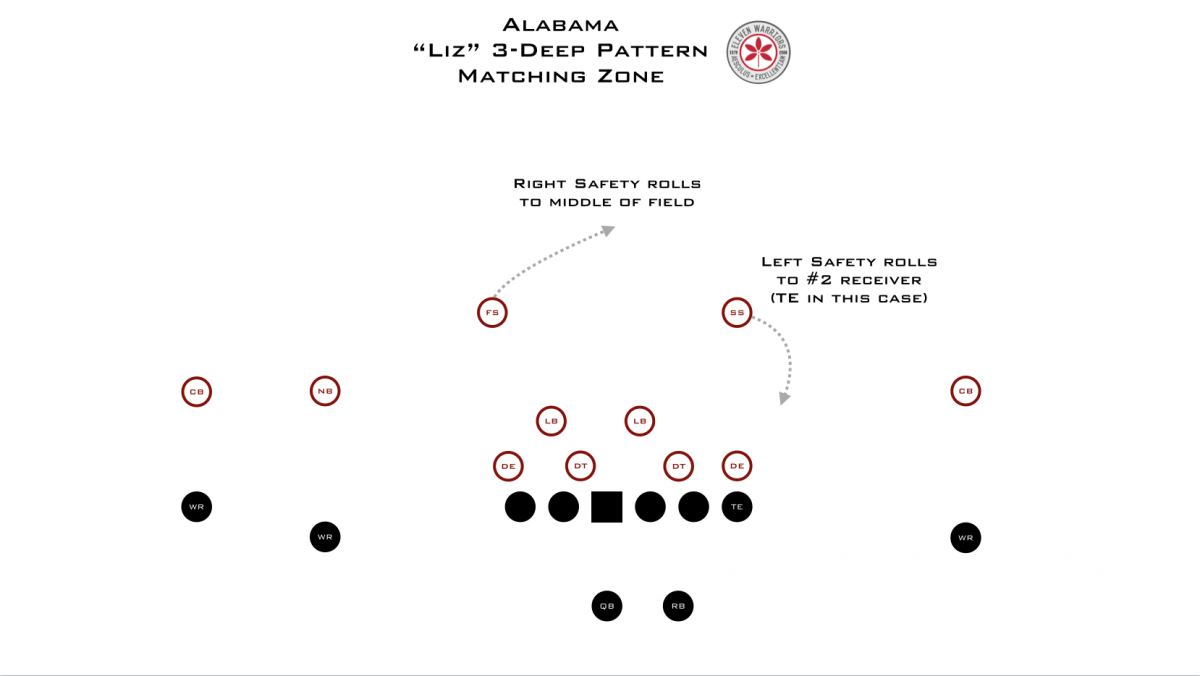

"We came up with this concept; how we can play cover 1 and cover 3 at the same time, so we can do both these things and one thing would complement the other. We came up with the concept 'rip/liz match.'"

Unlike a traditional zone defense, where a defender drops to a spot and reacts to any receiver that enters that area, Saban's pattern matching scheme is akin to a matchup zone in basketball. For those that aren't familiar with that hardwood concept, it simply means a defender defends their man with the technique of man-to-man coverage until he crosses with another receiver, at which time the defenders simply trade responsibilities instead of following the whole way.

This can often be very confusing for a quarterback, as the defense appears to be playing man coverage, which would open up certain patterns such as crossing routes or deep, vertical streaks like the routes Saban mentioned the Steelers ran.

The benefit for Saban and Alabama is that they can easily adapt it to whatever the offense throws their way. The defensive back is only dropping to play man coverage if the receiver takes off vertically. If the receivers cross though, they drop to play a zone, meaning their eyes are in the backfield.

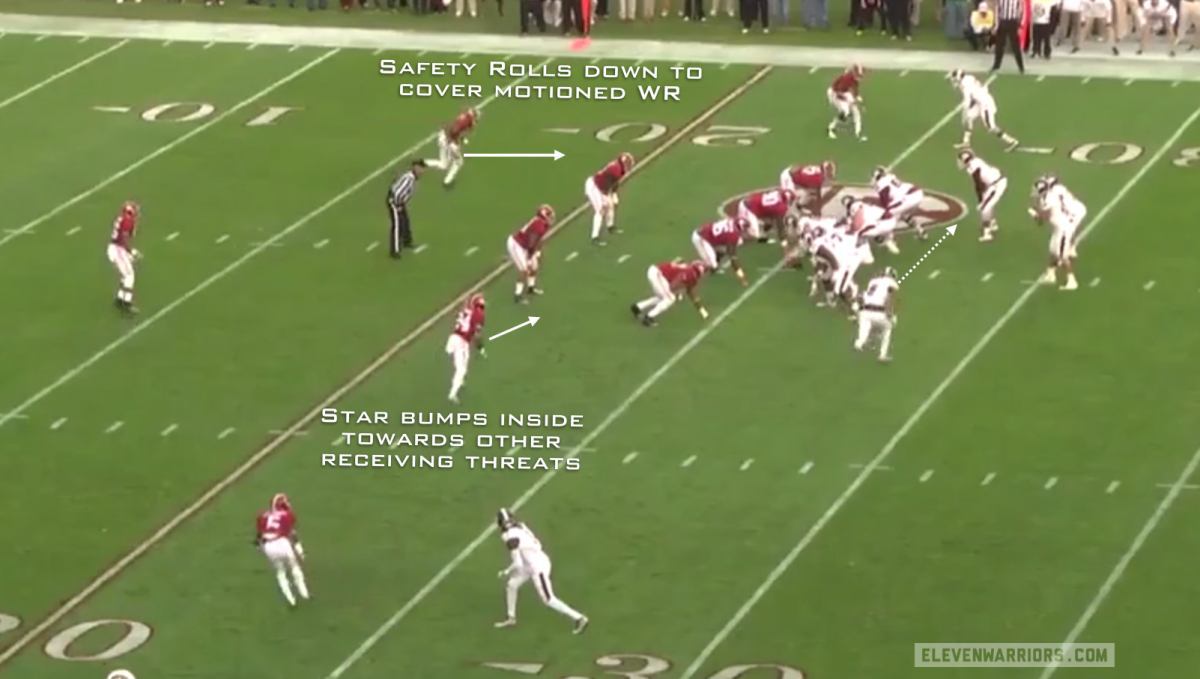

By rotating a safety to the strength of the formation into the box, Saban has also now created an eight man box where the defense isn't turning their backs to the line of scrimmage in coverage against a running play, meaning they're much better prepared to stop the run.

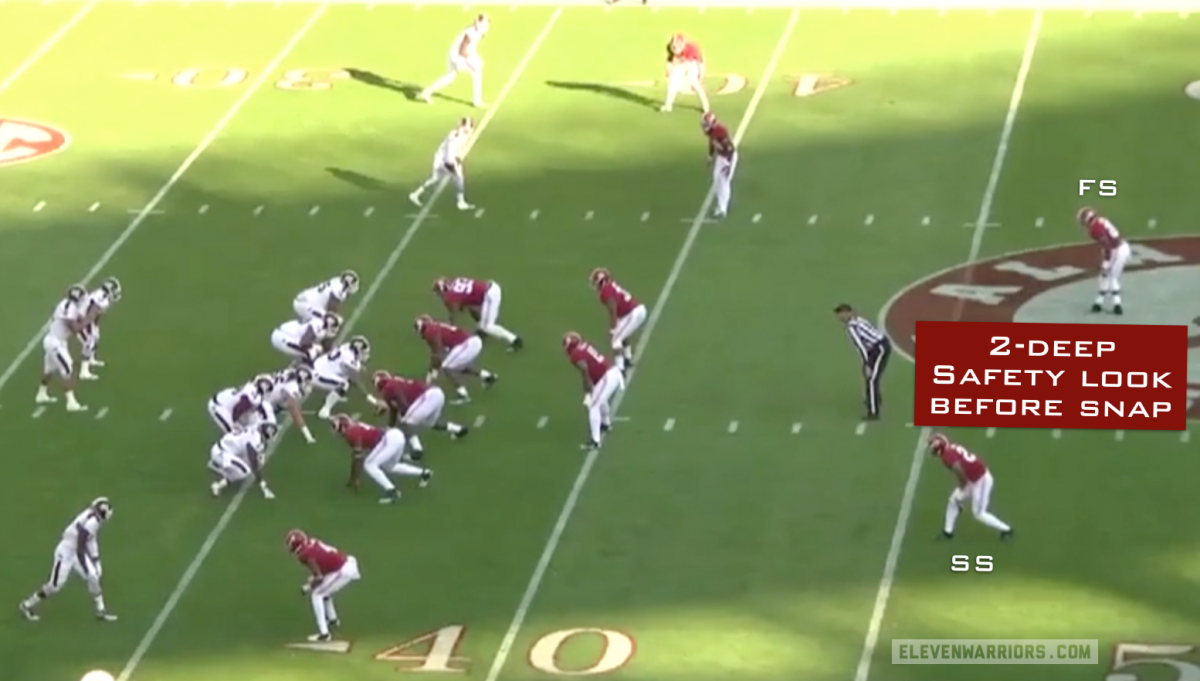

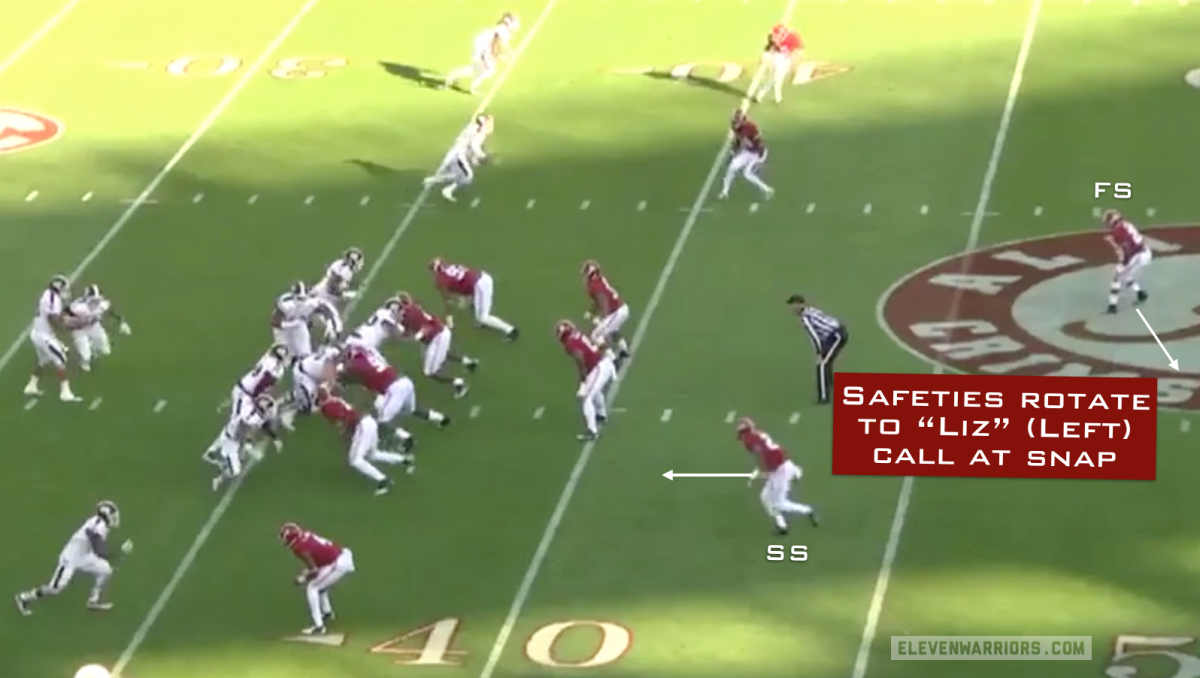

The "Rip" and "Liz" calls are simply calls that define the strength of the formation, and alert the defense as to which safety is rolling down toward the box. How Alabama defines the strength varies by scenario, and the shift of the safeties can happen before or after the snap, but the core concept remains the same.

A number of teams will roll their safeties to one side like this, so that action alone shouldn't be confusing for opposing quarterbacks. However, those defenses will simply play a regular zone after doing so, instead of the pattern-matching coverage the Tide employ.

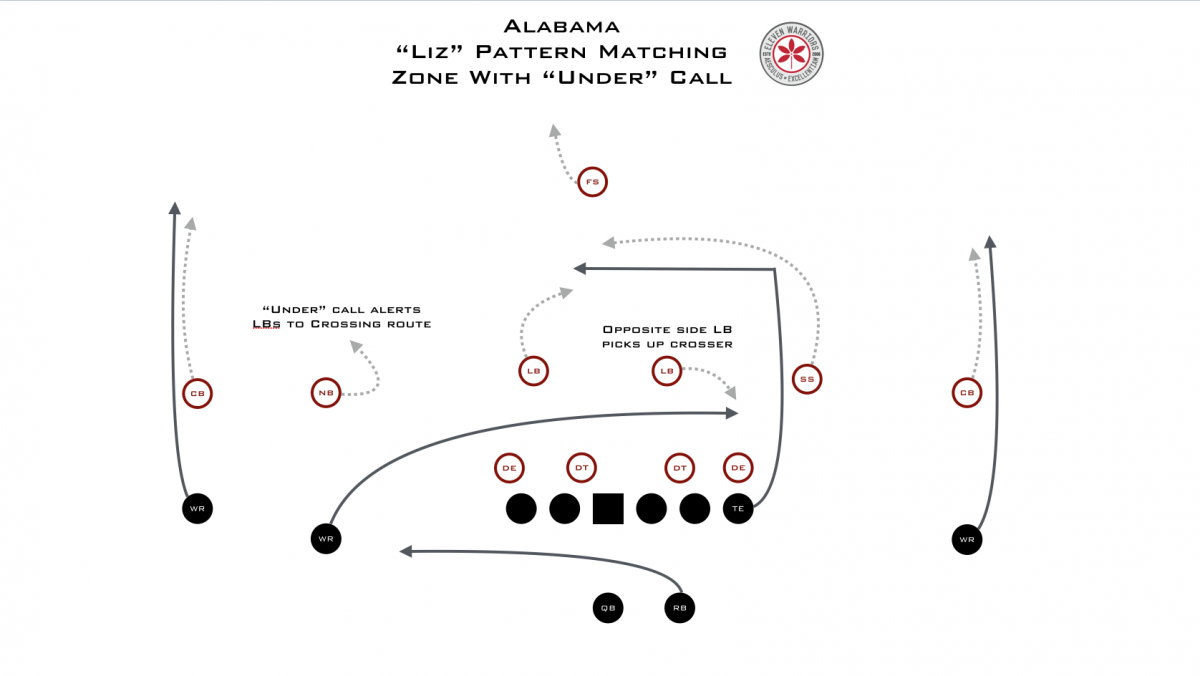

Many teams will try to beat this matchup zone with crossing routes, allowing the receiver to outrun his defender after he's been traded off. To defend these kinds of routes, Saban added in the "Under" call, which alerts the inside linebacker to the opposite side to undercut the crossing pattern.

If the linebacker right next to the receiver had to pick up the crossing pattern, he'd more than likely get outrun immediately, doing no one any good. But by giving the responsibility to the linebacker across the formation, Saban not only has a man waiting to make a tackle in the spot where the receiver will end up, but he's also given the illusion of a receiver running unguarded across the middle, baiting the quarterback to throw right to that backside defender.

Over the years, Saban and Smart developed countless additional wrinkles like this to counter specific formations, passing concepts, and the tendencies they identify in opponent scouting reports. For this reason, both coaches have gone on record to note that this scheme is extremely difficult to implement on the high school level with all its complications. It also speaks volumes to their abilities as teachers to consistently insert new players into the scheme over the past seven seasons with constant success.

As if that wasn't complicated enough though, Saban and Smart have another pattern-matching scheme that is reserved for clear passing situations.

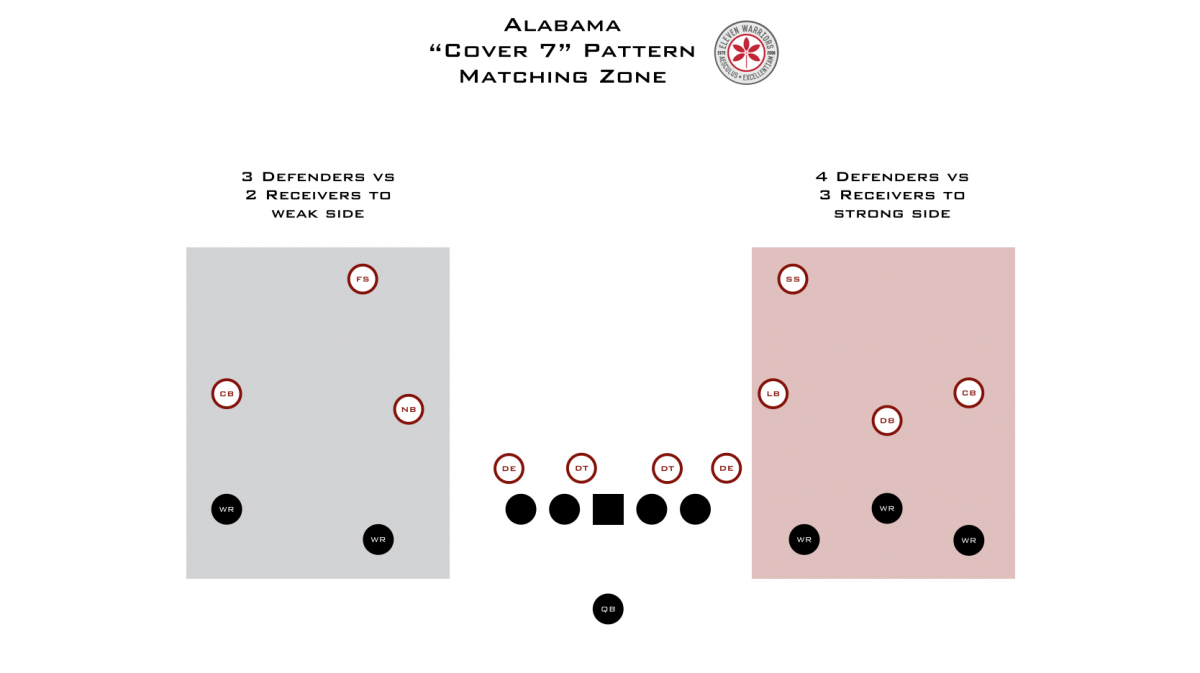

Called primarily against five-wide receiver formations that the Tide saw against West Virginia, Texas A&M, and Missouri, Saban's Cover 7 splits the field into two halves, dividing the two deep safeties and giving them a man advantage on either side. With this additional defender, the Tide have countless ways to bracket opposing receivers and confuse the quarterback.

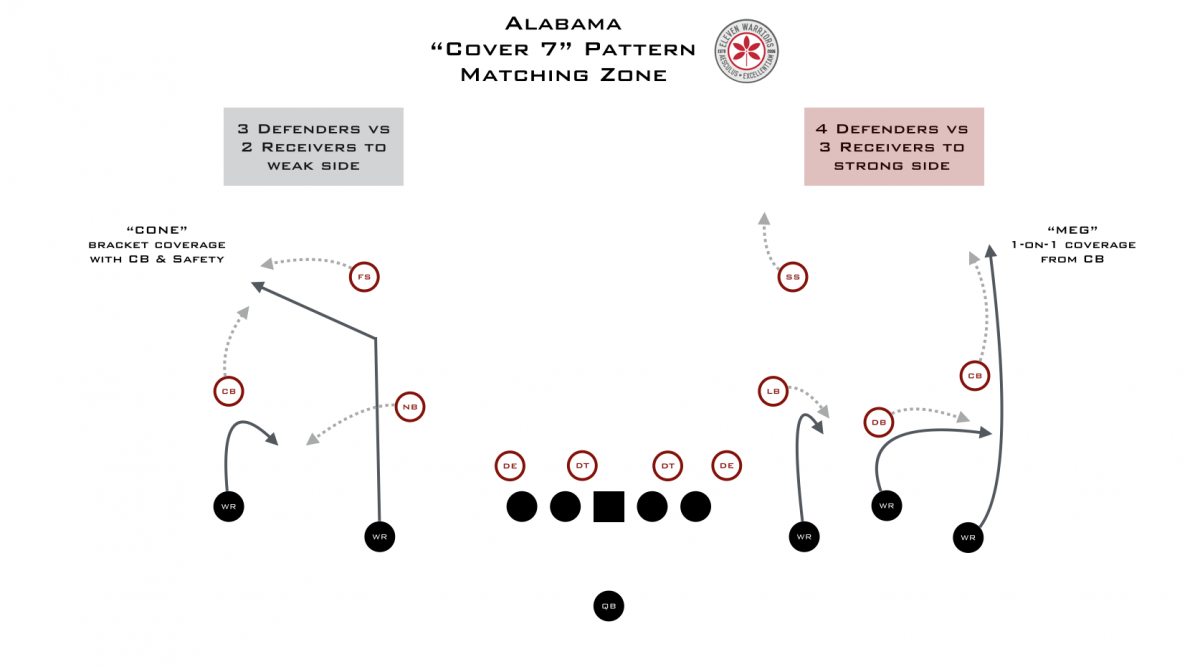

Though, much like in Rip/Liz, there are countless adjustments that are added in each week based on the opponent, the Tide have two calls that are implemented more than any other, and are critical to the way the cornerbacks will play:

-

MEG: the corner will play aggressive, man-to-man defense with no help

-

CONE: the corner will play off the receiver to the outside and bracket the receiver with help from the safety to the inside

With so few teams in college running a scheme like this, it can be very difficult to decipher when and where to throw on the Tide secondary. Of the "Power Five" conferences, only TCU runs something similar, and their system has its own set of intricacies.

To complicate things further, the Tide will mix these coverages with the regular zone and man schemes that can be found in every other playbook across the country. In this way, Saban's defense is truly the closest to what is found in the NFL, where game plans are built around the weaknesses of an opponent, rather than simply by what they're able to execute.

That doesn't mean it's unbeatable, however.

After finishing in the top 15 nationally in pass defense in every season since Saban arrived in Tuscaloosa, the Tide sit 58th in the category this year. Alabama's schedule did them no favors in that department, facing pass-heavy teams like the aforementioned Mountaineers, Aggies, and Tigers, as well as offensive juggernaut Auburn, who put up 456 yards through the air in the Iron Bowl.

Saban and Smart have consistently had the athletes needed to execute such a complicated scheme, and while they have one of the nation's best defensive backs in strong safety Landon Collins (#26), the Crimson Tide corners have been exposed this fall. Cyrus Jones (#5) has played well on one side, but is small in stature and struggled at times against bigger receivers like Auburn's Sammie Coates.

On the other side, Eddie Jackson (#4) and Tony Brown (#2) share playing time as neither has shown the consistency Saban and Smart have come to expect from their secondary. Knowing these corners are usually responsible for any deep route on the outside, opposing offenses have attacked them, looking to create situations where their receivers are in one-on-one situations.

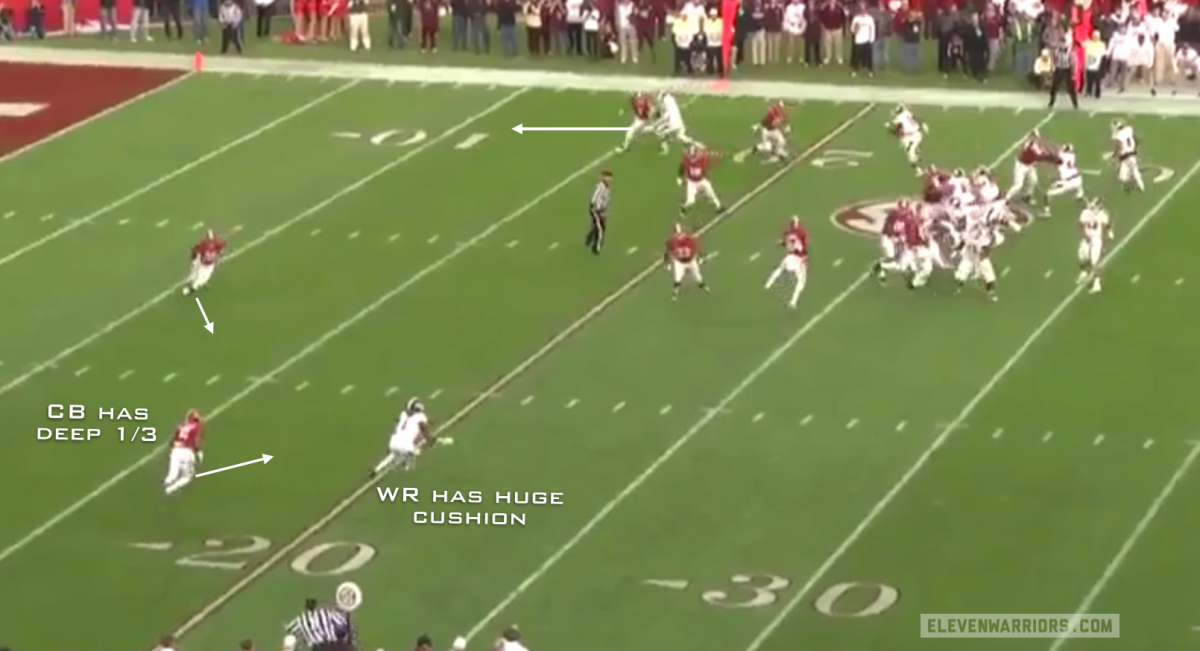

Since he has no help coming from the safety, Jones has to bail quickly, giving a big cushion to the receiver and allowing an easy reception. Ohio State has employed this same philosophy against off coverage, hitting Michael Thomas and Devin Smith for easy catches early and often against Michigan State.

But the Tide corners have had even more trouble when teams attack them over the top. Saban's defense has been very average when it comes to giving up big passing plays, once again bucking the trend of his previous squads. Though known more for their complex running game than their ability to throw, Auburn was able to light up the Tide thanks to countless deep balls to their big wideouts.

The Buckeyes should have plenty of one-on-one situations in the Sugar Bowl, and will have a quarterback with plenty of arm strength to get it there quickly in Cardale Jones. Considering that Jones is only making the second start of his career, we can expect Urban Meyer and the Buckeye coaches to try and simplify the game plan to focus on the outsides. Instead of waiting to decipher what the Crimson Tide safeties and linebackers are doing in the middle of the field, Jones will have a much easier go of it if he allows Smith, Thomas, and the rest of the Buckeye wide outs to beat the corners across from them and deliver an accurate pass.

It certainly won't be easy, but OSU was given a blueprint from a number of teams this fall. We'll find out this week if Jones and the Buckeyes are able to replicate it.