Ohio State’s varsity football team played nearly all of their games in Columbus during their first five seasons. Most of their games away from home were short train trips to Gambier, Granville or Westerville. They’d traveled as far as Cleveland and Cincinnati, but they hadn’t competed on foreign soil until November 1895 when they ventured across the Ohio River to play two games on consecutive days in the Bluegrass State.

The first game was on Friday in Lexington against the University of Kentucky, which was commonly referred to as Kentucky State at the time. The second contest was scheduled for the next day against tiny Centre College in Danville, Kentucky.

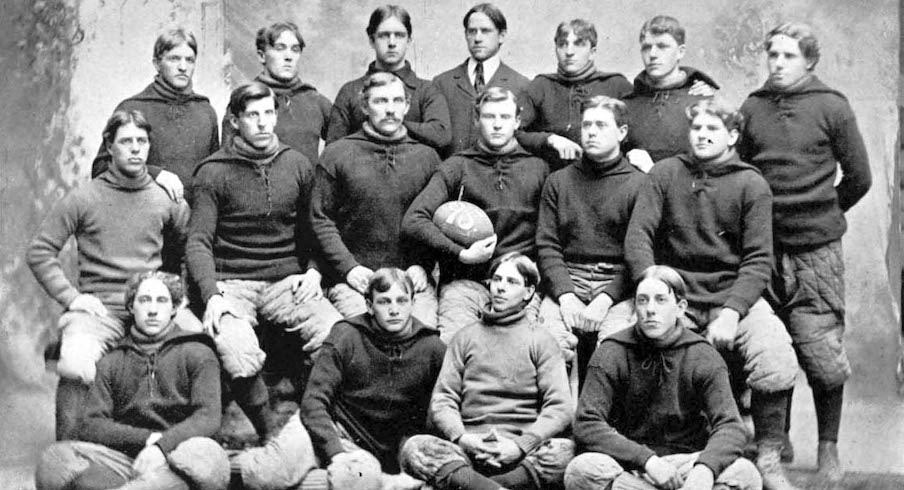

Considering the team would be playing on consecutive afternoons, coach Jack Ryder and captain Renick Dunlap would have been well-advised to bring than just the 16 players that made the trip. As it turned out, it would have been wise to have been accompanied by one or more of the companies of the OSU battalion.

The “Scarlet and Gray clad boys” arrived on Thursday afternoon to a city decorated with banners that served the dual purpose of promoting the game to the locals while cautioning their visitors.

“Watch Lassiter and Brown Crash the Tackles.”

“Watch Jackson and Boone Crush the Guards.”

“Watch Our Backs Run Over Their Ends.”

The weather was impeccable and the turf was fit for a sprint of The Bluegrass State’s finest thoroughbreds. Although every game from the era was hard-fought and often included slugfests, Kentucky deployed a specific cudgel to bludgeon their guests: their coach Charles “Chick” Mason. Mason wasn’t a student at UK – he’d used up his eligibility as a player at Colgate – but according to the recollections of Ohio State quarterback Homer Howard, Mason played the entire game and carried the ball on nearly every down. Mason pounded Ohio State’s defense and Howard received the brunt of the punishment by way of Mason’s “padded but sturdy knee.”

Ohio State led 8-6 at halftime thanks to Kingston, Ohio native Renick Dunlap’s 20-yard scamper around the right end for a score, followed five minutes later by a three-yard plunge by Frank Nichols of Wyoming, Ohio. Both “goal kicks” failed. At the time, touchdowns netted four points and PATs were worth two.

A tense second half was played with possession of the ball exchanged back and forth tantalizingly close to the OSU goal line. Averse to punting from inside their own 10-yard line, Ohio State repeatedly lost possession of the ball after exhausting its downs, only to heroically deny Kentucky from scoring. Only five yards was needed to gain a first down at the time, so the tactics more or less resembled two Bighorn rams repeatedly battering one another.

All the excitement and tension whipped up the emotions of some of the “super-loyal” Kentuckians in attendance. Ohio State’s players were acutely alert to the reactions of the locals, as word had filtered through that one Kentucky partisan had purportedly drawn a revolver on an opposing player and commanded the player to “take the ball back from the goal line” after scoring a touchdown in an earlier contest.

“No single bump was painful; but taken in bunches they became monotonous and then some,” Howard said to describe the punishment he endured during the game.

As the game wore on, Howard became so distressed that coach Ryder felt compelled to remove the Columbus native from the game. Ryder tied a handkerchief around his “aching head” and walked the wary quarterback to an awaiting streetcar. As Howard was stretched out recovering on one of the streetcar’s bench seats, a commotion caused him to sit up and look out the window.

“Very soon I heard a sound outside which caused me to look out,” said Howard. “Down the dirt lane they came! The ‘O.S.U.’ football team, each man, sweater in hand, was running in earnest. The air around and above them was fairly clogged with sticks, stones and other missiles. Back of the team came the mob.

“This particular streetcar had been built before the ‘pay-as-you-enter’ days,” Howard continued. “The windows were open, making easy entrance for the pursued football talent. The car was filled in record time. The last man to get on was the referee, an Ohio State man whose last outside job was to uppercut a bewhiskered member of the mob and leave him hanging on a picket fence.”

The streetcar was left exposed after someone in the angry crowd cut the lead and chased off the vehicle’s horses as projectiles continued to pelt it. In time, a posse of Lexington police arrived and escorted the unwelcome guests back to their hotel where they huddled in their rooms until after the mood had calmed down. They finally slipped out of town in the early morning hours under the darkness of night.

Physically beaten and emotionally drained, nearly everyone “felt like anything but playing football” when they arrived in Danville just two-and-a-half hours before kickoff the following day. Howard wasn’t the only Buckeye feeling battered. Michael Bahin, a tackle from Springfield, had injured his hand and had to be replaced in the second half by Canton native Carl Giessen. All of these factors contributed to the team’s inability to muster sufficient energy to play with their “usual snap and vigor,” and they fell to Centre 18-0.

“Experience had taught us,” Howard later recounted, “that sometimes discretion is the better part of valor – and our gang was agreed that this might be one of those times.”

No Ohio State football team has played in Kentucky since.

You can learn more about the early years of Ohio State football in the author’s book “Days of Yore: The Men of Scarlet and Gray,” which is available for purchase on Amazon. You can follow McQuigg on Twitter @dpmcquigg.