Offensive line play has long been romanticized.

Long before Michael Lewis wrote a best-selling book, countless sportswriters, broadcasters, and fans compared the often unglamorous work done by offensive linemen to that of modern-day gladiators. Every weekend, they engaged in brutal, hand-to-hand combat with oncoming raiders hell-bent on storming their castle and (literally) sacking their leader.

Lewis' now-famous chronicle of Michael Oher, a forgotten teen whose life changed thanks to his massive size and ability to protect others, brought the battle between left tackles and star pass-rushers into the mainstream. By 2009, even the most casual sports fan understood the need to protect a quarterback's blind side, raising the profile (and salary) of all parties involved.

As the sport evolved into the wide-open, pass-heavy game we see at all levels today, many assumed this battle along the left edge would gain even more importance. Every successful team needed not only a star passer under center, but a franchise left tackle to protect him.

But while offensive play-callers have seemed a step ahead of their opposing counterparts, setting records for both yardage and points on a nearly annual basis, there remains one critical element of the equation that cannot be ignored: in order for a quarterback to complete all those passes downfield, he must avoid getting pummeled by the much larger defenders trying to put him on his back.

Such has been the case for Ryan Day's program. While Justin Fields was often seen lighting up opposing defenses, there was a common theme in the closest games he played in a Buckeye uniform.

In Ohio State's one-score win over Indiana, the Hoosiers were able to register 11 pressures against Fields, while Alabama tallied 12 in the Buckeyes' lone loss of the season. In the CFP semifinal victory against Clemson, however, Fields was only pressured three times.

Though the Buckeyes have featured one of the nation's best, and most balanced, offensive attacks since Day and coordinator Kevin Wilson took over the offense in 2017, one of the lone areas of weakness appears to be pass protection. In 2019, Fields' first season under center, OSU finished 99th in the nation in sacks allowed per game, improving just marginally (91st nationally) last season.

With most opponents on Ohio State's schedule incapable of competing with them head-to-head based on raw talent, Day and his staff typically see a wide variety of pressures meant to get to their QB before he can unleash a pass to one of the many talented receivers on the roster. If given the time to do so, the Buckeye offense has proven capable of shredding any coverage thrown its way, from Don Brown's aggressive man-coverage to Wisconsin's diverse zone-match schemes.

While they still spend plenty of time focused on the coverages employed by their secondaries, great defensive minds like Nick Saban and Brent Venables spend as much time focused on the one area in which the playing field is more even. Instead of lining up their best pass rusher across from the left tackle on every snap in the hopes of forcing a rare mistake, these defensive play-callers have found ways to create pressure and collapse the pocket elsewhere with a plethora of exotic alignments and pressure packages meant to confuse over overwhelm offensive lines without sacrificing coverage on the back end.

For instance, Alabama's Christian Barmore was one of the nation's most productive pass rushers last season (Pro Football Focus gave him the fifth-best pass-rushing grade among all defensive linemen and edge defenders last season). The All-SEC player lined up most frequently in the B-gap between the guard and tackle (298 snaps), but could also be found in the A-gap (82 snaps), directly over the offensive tackle (82 snaps), or out on the edge like an end (15 snaps). Such variance made it nearly impossible for an offense to build a protection scheme around stopping Barmore, allowing the big man to tally 8 sacks and 27 hurries last season.

With defenders changing their alignment from play-to-play, offensive protection schemes have tried to evolve in kind. At the NFL level, teams often carry dozens of protections, sometimes spending an entire practice in training camp installing a single scheme meant to combat just one opponent.

But college teams rarely have that luxury. Like their counterparts in the defensive secondary, most offensive line coaches at this level are still focused primarily on refining the techniques of their still-maturing players, meaning there is only so much time that can be dedicated to implementing extra pages in the playbook.

Additionally, with offenses running more 3 and 4-wide alignments, there are only so many different ways in which they can create a pocket around the QB. Along with the five offensive linemen, the sixth blocker is most often the running back - not because he is superior to a much larger tight end when it comes to stopping a pass rusher, but because of his location in the backfield. Instead of being affixed to one end of the line, the back provides more flexibility by starting in the middle of the action and can fill a gap anywhere along the line.

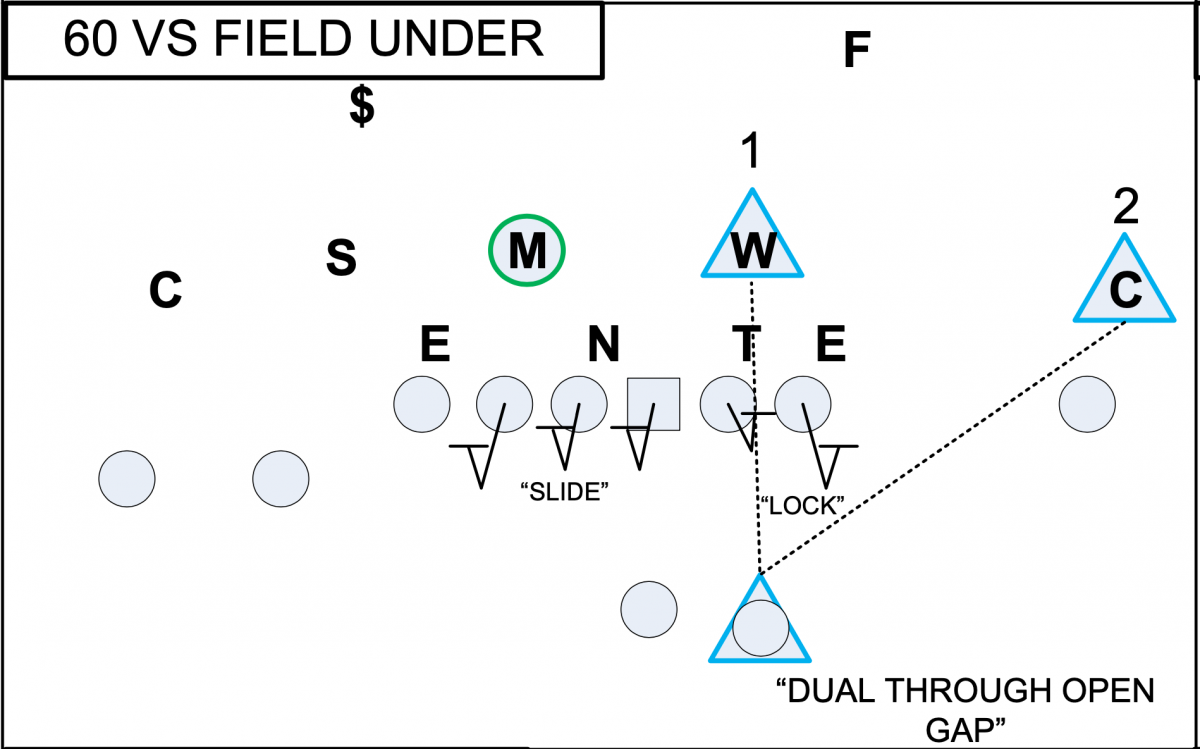

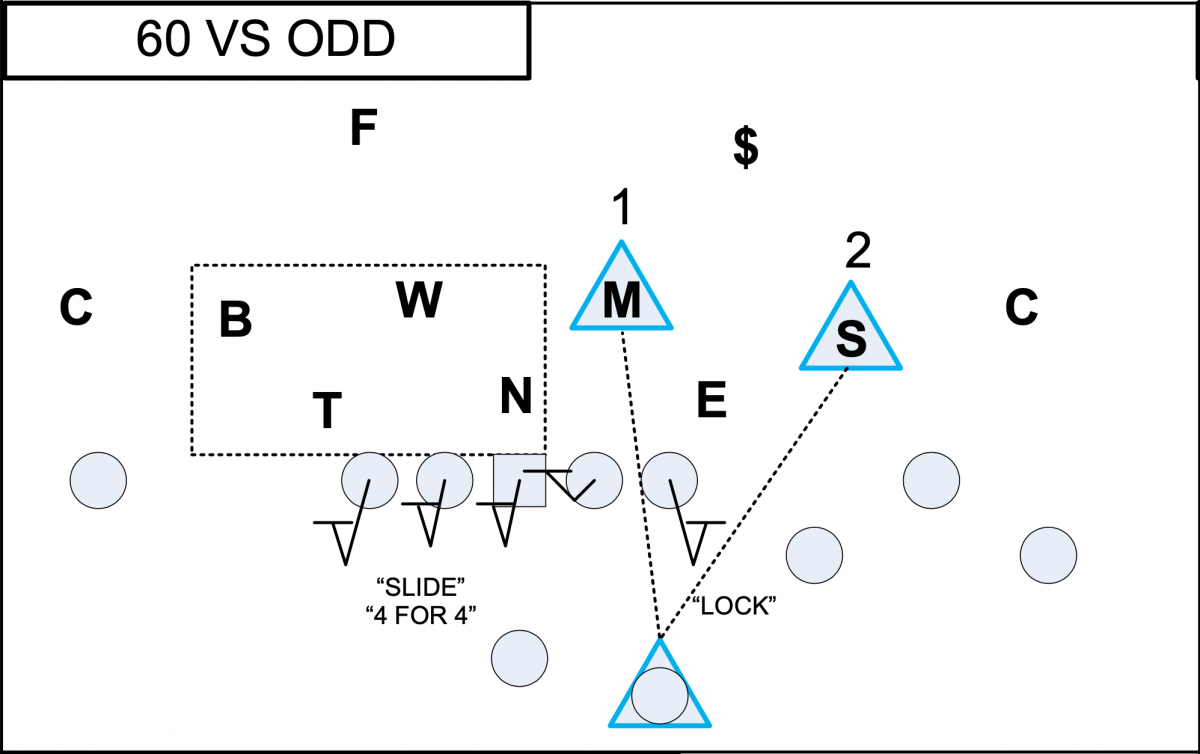

The most common type of 6-man protection seen at both the college and pro level combines zone-blocking principles on one side with man-blocking on the other. In this concept, known as a 'Half-Slide' protection, the center will team up with the guard and tackle to one side, cutting off any pressure in their gap in that direction, much as they might on a zone run.

On the other side, the blockers will employ a 'Big-On-Big' (B.O.B.) scheme in which the guard and tackle each lock onto the down defensive linemen across from them, focusing entirely on slowing that one, single defender. Meanwhile, behind them, the back will look to the second-level defenders like linebackers or a lurking safety and pick them up if they blitz.

The key player in this scheme is the guard on the man-side, as he must work with the center to ensure no one slips inside the A-gap between them. If a down lineman sets up between them or directly over the center, the guard will then join the opposite side in their slide technique, leaving just the tackle and the back to man the other way.

Against typical defensive looks that send pressure with a four-man front and drop the remaining seven in coverage, this concept is often quite successful. With only one blocker capable of getting beat one-on-one (the man-side tackle), quarterbacks often have plenty of time to find an open receiver and deliver the ball accurately.

But defensive coaches understand these rules and know how to use them against the offense. By scouting an opponent's tendencies and anticipating when and where they'll attempt a dropback pass with this protection, defenses can choose to overload one side of the protection without sacrificing coverage integrity.

The defense doesn't even need to send seven or eight defenders on a blitz, leaving the secondary exposed. Instead, they start by often dropping a defensive lineman or two on the man side into coverage.

As their assigned responsibility falls back away from the line, the man-side blockers are effectively taken out of the play with no one to block. Meanwhile, the defense overloads the opposite side with extra rushers, leaving the offense a blocker short.

Such blitz packages not only create pressure on the quarterback but force him to diagnose a strange coverage on the fly. As the middle linebacker rushes through the A-gap on a blitz, a 300 lb D-lineman comes flashing into the area he just vacated, leaving a messy picture for the QB to dissect with no time to waste.

Regardless of who wins this summer's competition for the open role, whoever starts at quarterback for Ohio State this fall will be doing so for the first time. Given that none of the three competitors vying for the job have ever thrown a pass in a college game, their coaches might want to do whatever possible to ensure they aren't facing a barrage of blitzers when they do finally drop back.

Note: this is the first in a series exploring the chess match between modern pass protection schemes and the pass rushers hellbent on beating it. Next week we'll examine the way Tom Allen's Indiana defense has used pressures like the ones above to elevate the entire program to another level.