It has become an annual event. Every spring, NFL analysts break down whether this year's group of signal callers can develop into the mythical franchise quarterback.

The unending search by NFL teams for a top-level quarterback is not limited to the draft. Offseason acquisitions by a team to shore up other needs are often met with a yes, but. Yes, this team improved at [position X], but it is ultimately irrelevant until they find their Tom Brady or Peyton Manning.

Yet despite this never-ending search, for many teams the quarterback quandary remains. This makes some sense. By definition, not every team can have a top-10 quarterback. And despite extensive analysis, drafting a quarterback is largely a crapshoot. We largely lack methods to identify what college quarterbacks will be successful pros.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that the NFL currently cannot find 32 competent quarterbacks. By some accounts the talent at the position is getting worse. So for those NFL teams continually struggling to find a quarterback it is worth asking – is there another way?

The Paradox

With the rise of shotgun spread offenses in college, the analysis of quarterback draft prospects has taken on a particular form. Exemplified by Marcus Mariota this year, the annual question is this: how will [spread quarterback X] translate into a pro-style offense?

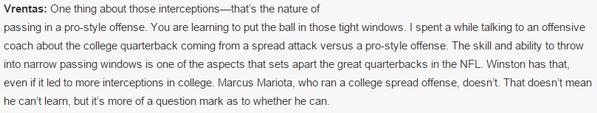

Yet a deeper dive into the analysis makes you wonder if NFL organizations are asking the right questions. For instance, one analyst – in contrasting Mariota with Jameis Winston – said the following:

In other words, according to this analyst, a pro-style system results in less separation for receivers, which leads to more interceptions. As Chris Brown points out, why would you want to use an offensive system that gets people less open and results in more turnovers?

Ignore NFL translation, isn't this weird? Prostyle is better because it produces less open guys/doesn't work as well? pic.twitter.com/wfChgwGzdN

— Chris B. Brown (@smartfootball) February 26, 2015

History Repeats Itself

Given the spread's ubiquity in college, it is easy to forget that its rise in college was also driven by simplifying decision-making for the quarterback. A traditional pro-style system increases the defense's arithmetic advantage. And it is difficult to find individuals who can read five receiver progressions across the field while staring down a pass rush in the pocket.

Enter the spread. By forcing a defense to account for the quarterback as a potential run threat, it tilts the arithmetic back towards the offense. And forcing the defense to defend the entire field – namely the potential for an inside run, a quarterback keep or a quick throw off the quarterback reading an unblocked defender – results in more open spaces, leading to easier completions.

Further, the spread can create more open receivers by taking advantage of weapons the rules afford the offense – namely making plays look alike and faking. Throws often come off inside run action. And there is no better fake then when the quarterback is actually making reads.

The Injury Threat

The most cogent argument against utilizing a spread offense in the NFL is the threat of injury. By utilizing your quarterback as a run threat, you risk more hits on a critical player – one in whom who your owner invested a large sum of money.

While that threat is real, several factors mitigate that risk. The first is that utilizing spread principles does not necessitate a consistent quarterback run threat. One of the foremost spread practitioners – Chip Kelly – has led the Eagles to two consecutive double digit win seasons with largely stationary quarterbacks.

Perhaps less noticed, one of the league's most successful teams – the New England Patriots – uses a spread passing offense grafted together with an under-center power run game. In short, a team can use spread principles such as packaged plays and the quick, horizontal passing game without running its quarterback. (H/T: James Light).

And injury is not a foregone conclusion. Under Chip Kelly's former quarterbacks coach (Bill Lazor), Miami Dolphins quarterback Ryan Tannehill threw for over 4,000 yards, increased his completion percentage to 66 percent, cut his interceptions from 17 to 12 and ran for 311 yards – all while frequently operating from the shotgun. Yet Tannehill appeared in all 16 games.

More pertinent, perhaps a spread offense provides the opportunity to slightly devalue the position. If a team is struggling to fill the position, what is easier to find? One pocket passer, or several guys who can thrive in a spread offense? College teams have found the latter.

If a quarterback is injured, there is a deeper pool to draw from. One needs only look at college football's national champion, Ohio State, who won the national title behind their third string quarterback, Cardale Jones. The Buckeyes were admittedly blessed with three talented quarterbacks, but Urban Meyer's spread system – by altering arithmetic and stretching a defense horizontally – made it easier for a quarterback to succeed.

Given most NFL teams' hesitance to utilize spread principles, a franchise that does embrace the spread would be in an enviable position. College is producing a bevy of spread quarterbacks who do not necessarily have the tools to thrive in a pro style offense. For a team that cannot find one pro-style quarterback, why not pick up multiple spread quarterbacks, reducing the potential harm to the team from an injury?

Will it work? Maybe, maybe not. But for franchises that have struggled for years to find a franchise pro-style quarterback, is it not worth a shot?