Ever since Chip Kelly arrived in Eugene in 2007, the Oregon Ducks have done things a little bit differently.

Though Mike Belotti had led the transition of the program from Pac 10 pushover to regularly winning 10 games, it wasn't until Kelly's hiring that the Ducks made the leap to national contender. His impact on the University of New Hampshire, the University of Oregon, and now the Philadelphia Eagles has been documented in great detail, showing a coach that constantly tries to re-think the way he and his coaches approach every aspect of their programs.

But although Kelly is now busy re-making the Eagles in his image, he left the Ducks in good hands with his former top assistant and offensive coordinator, Mark Helfrich. Helfrich only coached with Kelly for four seasons in Eugene, but it's clear that he is a full believer in the non-traditional ways of his former boss.

Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than the tempo at which the Oregon operates on offense, where the Ducks often move at breakneck speed between plays. But this isn't a part-time philosophy, as Helfrich explained at a coaching clinic in 2013 shortly after taking over the head coaching job:

"We use it and believe in it. The defense believes in it and the strength coach believes in it. The philosophy of being a no-huddle team has to be program wide. The idea of going fast has to be in every phase of the program. It starts with the offensive scheme, our conditioning, it continues in the weight room, and includes the defense.

...

"Everything we do from a conditioning standpoint and the weight room is about playing fast. In the weight room, we go fast, fast, fast, and pause. That activity assimilates a series on offense. In our practice schedule, we never go more than 12 minutes in a row in the team setting. If we had a 20 minute team drill, the players would die. We try to go as fast as we possibly can for a maximum of 12 minutes."

Although the uptempo, no huddle attack has become very common around college football over the past half decade, Oregon has continued to find success with it thanks to their complete commitment to its implementation. As the Buckeyes prepare to take them on with the national championship on the line, they'll prepare to face an opponent unlike any other they've seen this fall.

Offense

Beyond the hundreds of uniforms, the most defining characteristic of the Oregon program is their aggressive, yet simple offensive scheme. Though Kelly has been known to be very secretive about many aspects of his program, play-calling isn't one of them.

As he explained in a press conference during training camp with the Eagles last summer, “I’ve said it since day one: We don’t do anything revolutionary offensively. We run inside zone, we run outside zone, we run a sweep play, we run a power play. We’ve got a five-step [passing] game, we’ve got a three-step game, we run some screens. We’re not doing anything that’s never been done before in football.”

Ross broke this down in much more detail, but the Ducks' playbook is no different than any other team, running all the same plays as every other "spread" offense. What sets them apart though, is how they call those plays.

Within their uptempo, no-huddle approach, the Ducks will go back and forth between three "speeds" when they have the ball:

- Red: Rarely utilized, this is when they actually huddle between plays. The Ducks often only call for it when taking a knee to end games.

- Yellow: The form of no-huddle run by most college teams, where the offense lines up immediately after the previous play, then looks to the sideline for any adjustments from the coaching staff based on the defense's alignment.

- Green: The speed for which they are known most, the Ducks will line up and snap the ball as quickly as possible after the ball is set by the officials. When running this speed, they'll rarely switch formation from one play to the next, and very often call the same plays over and over.

In the Rose Bowl against Florida State, the Seminoles had a great deal of trouble slowing down the Oregon attack once they entered "Green" mode, which led to multiple scores.

The reason for this speed is simple, as they're trying to catch the defense off guard and attack their weakest areas. Helfrich explained how in that same clinic speech:

"We do not get in attack mood to see what they are doing. We get in attack mood to see where we can attack. We want to train our players with a forward lean.

"We try to strain the defense from an alignment standpoint. We want to know, are they trying to get additional personnel on the field? Are they using a nickel or dime package in particular downs? We hope we can limit their answers to a scheme we may be using. If they cannot get their nickel package into the game, does it hurt what they are doing?"

Beyond simply wearing out a defense, Helfrich and the Ducks are looking to expose any weaknesses that might appear. To compliment their uptempo approach, the Ducks constrain defenses better than possibly anyone in the country, building a series of plays that look alike off one another.

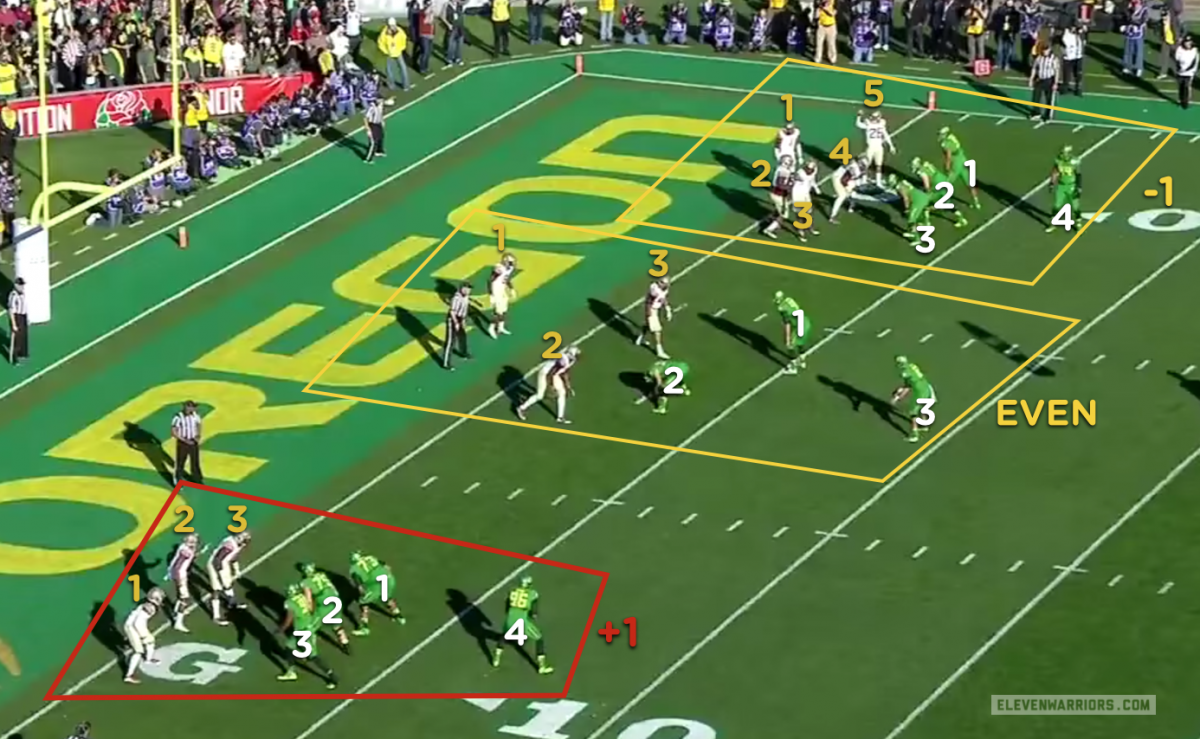

Defenses can't guard against every potential attack at all times, and the Ducks use simple arithmetic to define where they go with the ball. If the defense commits an extra defensive back in the box to stop the run, they'll throw the screen. If they put a linebacker in the slot to stop a wide receiver screen, the Ducks are more than happy to run inside.

As Helfrich noted in his speech to the coaches, "What we try to do from a game plan standpoint is to line up and have answers. We want to have something that is all-purpose from all formations. In a 3x1 formation, we want to be able to run the ball to the strong side and weak side. We want to have play action off each of those plays and get the ball snapped quickly."

The uptempo style only accelerates things for the defense, often causing defenses to line up incorrectly, making the Ducks' job that much easier to find a weak spot. This philosophy can be seen everywhere in the Oregon offense, even on extra points. After the first touchdown of the Rose Bowl, Florida State was caught unprepared allowing the Ducks to throw an easy screen pass to the left that resulted in a two-point conversion.

To properly orchestrate this scheme, the Ducks ask a lot of their quarterbacks. While they've had a number of very good players at the position in the past like Dennis Dixon and Darron Thomas, none has directed the Oregon offense quite like Marcus Mariota. The nation's leader in passing efficiency earned the Heisman Trophy with an absurd 40 touchdown passes to only three interceptions.

While an overwhelming number of his throws are screen passes, which act as an extension of the Oregon running game, he still managed to lead the country in yards-per-attempt with an average of 10.1 on his way to over 4,100 passing yards this year. Though this heavy reliance on screens and short passes has been used an as excuse for pro scouts to properly judge him, he still has shown an ability to make good decisions and deliver the ball into tight windows.

But no Oregon quarterback is asked to simply throw the ball, and Mariota once again has set a high bar for any of his successors when it comes to running. Though he's not built like a running back, Mariota possesses excellent acceleration, and must be accounted for in the read-option game.

Though the Buckeyes have beaten a number of mobile quarterbacks this year like Keenan Reynolds, Devin Gardner, and Blake Sims, they haven't seen anyone quite like Mariota. As defensive coordinator Chris Ash said this week in an interview with BTN.com, "The closest thing I have played against was Braxton Miller when I went against him. We have not played a quarterback as dynamic as him by any means this year."

His ability to drive the running game isn't due only to his legs though, as he has seemingly mastered the art of running the option, rarely making the incorrect read. With him at the helm, the Ducks have built an extremely diverse option game, creatively using motion and often including players that often would have no part in such a play.

When he does give the ball to one of his teammates, they're more than capable of picking up yards themselves. With freshman Royce Freeman (#21) and sophomore Thomas Tyner (#24) sharing the load with Mariota, the Ducks have a number of capable options in the backfield at all times.

Freeman has received the majority of the carries this fall on his way to over 1,300 yards and 18 touchdowns, and may remind Ohio State fans of Ezekiel Elliott with his good balance of speed and size. Tyner will come in to spell Freeman regularly, and was the more effective of the pair in the Rose Bowl, where he tallied a season-high 124 rushing yards. Though listed 14 lbs lighter, Tyner is also the more physical runner of the two, and adds a physical element to the Ducks' running game that hasn't been there since LeGarrette Blount played in Eugene.

The pair have been so effective that junior running back Byron Marshall, a 1,000 yard rusher in 2013, has transitioned to the Oregon equivalent of OSU's "H" receiver role. But Marshall has also thrived in this role, leading the Ducks in catches and yards by a wide margin, often on the receiving end of all the aforementioned screens.

But Marshall will have to carry a much heavier load against Ohio State, as the Ducks are without three of their top five receivers. While much has been made of suspended wideout Darren Carrington, Mariota will also be without the speedy Devon Allen, who suffered a leg injury on the opening kickoff of the Rose Bowl, as well as tight end Pharoah Brown. A native of Lyndhurst, Ohio, Brown had emerged early in the year as Mariota's favorite target downfield, showing good hands to go with his huge frame.

Without the trio of Carrington, Allen, and Brown, the Ducks will have to do their best to avoid long third down passing situations. Not only will there be fewer experienced options downfield, but Mariota is also playing behind an offensive line that has been decimated by injuries this fall. Though bolstered in the Rose Bowl by the return of 3-time all Pac-12 center, Hroniss Grasu, the Ducks have had serious problems protecting their quarterback, giving up at least three sacks on six separate occasions this season.

Knowing that the Ducks are weakest when facing these long yardage situations, it's critical for the Buckeye defense to get stops on early downs. The Ducks rarely run the "Green" phase of the no-huddle when they aren't picking up yards, making these early stops critical.

While much of the focus has been on the back end of the Buckeye defense against such a talented quarterback, this battle will be won up front, as the weakest part of the Oregon offense goes up against Michael Bennett, Joey Bosa, and a talented defensive line that might be the strongest unit on the team. If the OSU front line is able to win their individual battles and get penetration in the backfield, the Ducks could find themselves in a hole they rarely see.

Defense

Luckily for the Buckeye offense, their job should get easier after taking down the Alabama defense in the Sugar Bowl. The Ducks feature a pass defense that ranked 111th in country to go with a run stopping unit that was just average by nearly every metric.

However, it's hard to properly judge the Oregon defense by numbers alone. Often playing with a significant lead, the Ducks faced more passing attempts than all but one other team in the nation. However, they only allowed 6.7 yards-per-attempt, which equalled that of Michigan State at 38th in the country, a much more respectable measure.

But if there is one metric that defines the Ducks' defense, it's turnovers. Knowing that Mariota and the offense often end their drives in the end zone, Helfrich and his staff place a premium on takeaways.

"If you watch our defensive players, you will see they all have their eyes on the ball The first defender secures the tackle and second and third defenders attack the ball," Helfrich said at the coaches clinic, before going on. "We want our defense to swarm the ball, with an attacking nature. That leads to a takeaway."

The results here speak for themselves. The Ducks had the second-highest turnover margin in the country, committing the fewest turnovers of any team while forcing 20 fumbles, 18 of which they recovered.

Much like the Buckeyes, the Oregon defense is anchored up front by a big, athletic unit that looks like a basketball team more than a typical collegiate defensive line. Ends Arik Armstead (#9) and DeForest Buckner (#44) are both listed at over 6'7" and 290 lbs, and the duo has combined for over 18 tackles-for-loss this year while using their big frames to cause problems for opposing blockers.

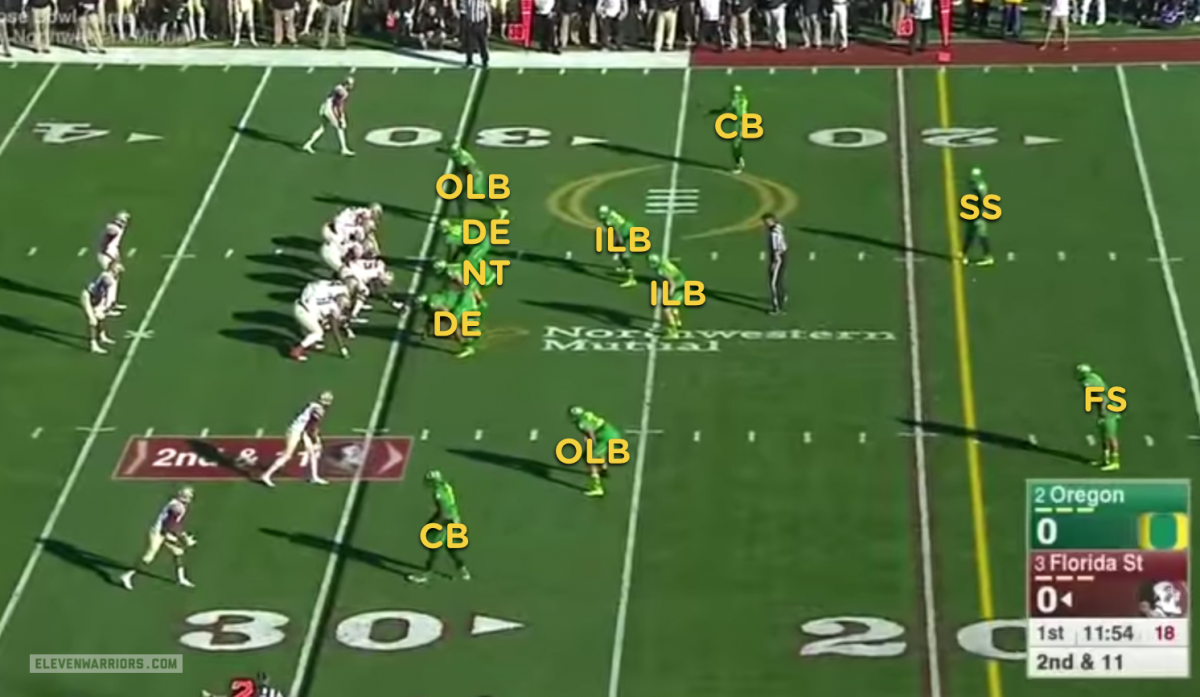

Lined up in a 3-4 base defense, the Ducks attack with many of the same one-gap principles found on a four-man line, often walking outside linebacker Tyson Coleman (#33) out over a slot receiver and leaving Tony Washington (#91) as a stand up defensive end next to Armstead.

Behind the big front line are a trio of linebackers that rotate at the two inside positions. Derrick Malone (#22) leads the group in tackles, but is smaller than Joe Walker (#35) and Rodney Hardrick (#48), who at over 240 lbs, both possess size similar to what the Buckeyes saw from Alabama.

But unlike the Tide's inside linebacking corps, Oregon's group doesn't do a great job of getting off blocks before giving up yards in the running game. Florida State's talented line gave the Oregon front big problems before succumbing to countless fumbles in the second half, and both Seminole running backs averaged nearly seven yards every time they carried the ball.

Though the 'Noles prefer the outside zone run more than any other, they also saw a great deal of success with the inside zone, which is the foundation of the Buckeye offense. The Ducks often over-pursue to gaps, allowing cutback lanes that Ezekiel Elliott should be able to find.

With so many running plays getting to the next level, it's no surprise that Oregon's leading tackler is strong safety Erick Dargan (#4). He and cornerback Troy Hill (#13) lead a secondary that is often called upon to help in run support, but are without their most talented player going into their biggest game of the season.

The loss of all american cornerback Ifo Ekpre-Olumu to a serious knee injury dealt a huge blow to a unit that is used to getting tested by opponents. However, the Ducks have gotten better on the back end as the season has progressed, seeing their opponents' passing efficiency drop along the way.

Much like the offense, Oregon's defense isn't very unique from a schematic perspective. The secondary often keeps both safeties deep against the multiple wide receiver looks that the Buckeyes will bring, playing a combination of Cover 2 (deep halves), and Cover 4 (quarters) zones.

While announcers often call Oregon a "bend, but don't break" defense, the numbers don't necessarily back that up. They haven't been especially stout when opponents get in the red zone, relying instead on forcing only a handful of stops and turnovers, which is usually all the offense needs to create a substantial lead.

But overall, the Buckeyes will have chances to pick up yards on this defense. Though the final score made the Rose Bowl look like a blowout, Florida State still amassed 528 yards of offense that afternoon. Like so many other teams over the past half decade, turnovers sunk the Seminoles, allowing the Ducks to get out to a big lead in a matter of minutes.

Aside from the mistakes against Virginia Tech and a snowy day in Minnesota, the OSU offense has done a pretty good job of taking care of the football. They'll have to place a premium on ball security against Oregon though, knowing that if they're able to hold on to the ball, they'll be the ones to light up the giant scoreboard in AT&T stadium.