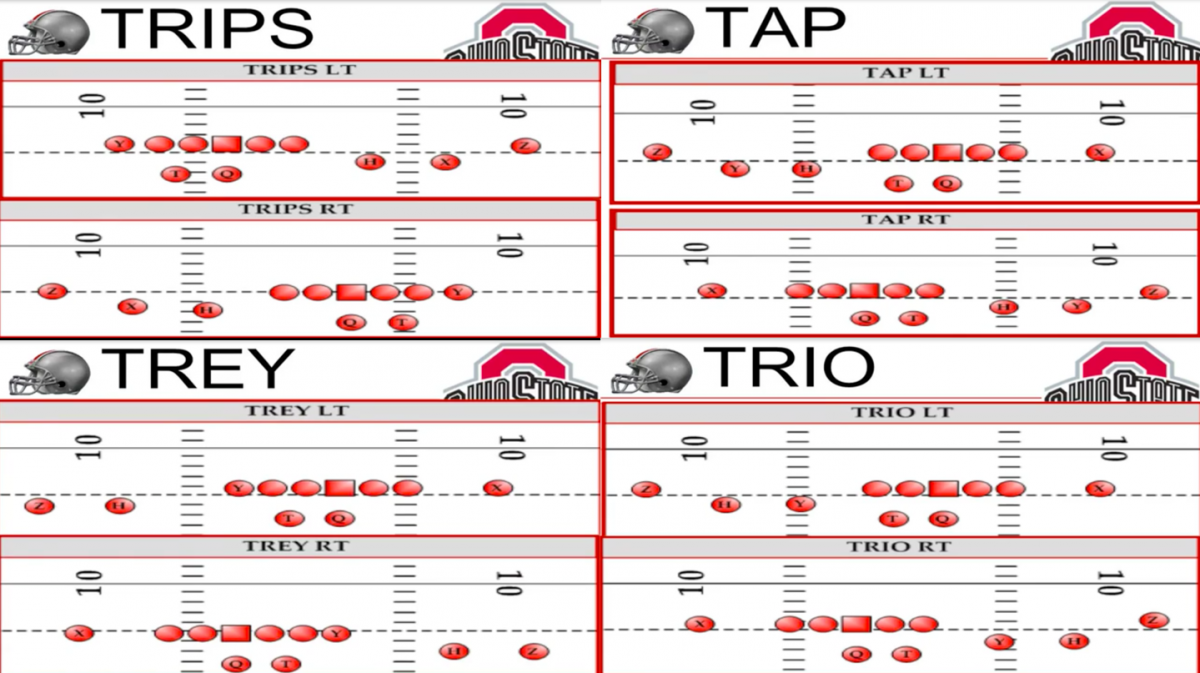

When Urban Meyer, Tom Herman, and the rest of their offensive staff began installing Ohio State's new offense in the spring of 2012, players inside of the Woody Hayes Athletic Center were introduced to seven different formations in their new coach's spread-to-run shotgun system. While the most notable change from the prior regime appeared to be the permanent removal of a fullback in favor of an additional receiver, the new system would look to stretch the field both vertically and horizontally with multiple receivers lined up from sideline to sideline.

But of the seven new alignments introduced to the Buckeyes that spring, four of them would overload defenses by featuring three receivers to one side. What had previously appeared to be a gimmick would now become the default.

In only six short years since the system's installation, Meyer and the Buckeyes have amassed a record of 73-8 while rewriting the offensive record books along the way. Clearly, something is working.

But during this relatively brief period, the way opponents have defended the team in scarlet and gray has evolved a great deal. Notably, pattern-matching schemes that mesh the spatial responsibilities of zone defenses with man-coverage techniques have become the norm in the modern game. Even the Buckeyes themselves invested heavily in such a philosophy upon the arrival of Chris Ash in 2014, winning a national championship that season after shutting down the vaunted Oregon Duck offense.

Of the aforementioned eight losses experienced in the Meyer era to this point, though, half have come at the hands of Mark Dantonio of Michigan State and Brent Venables of Clemson, two of the game's premier defensive minds. While Dantonio's system is far simpler on paper than that of Venables, both have found ways to vex Meyer and his staff on multiple occasions, thanks largely to their abilities to take away the inherent advantages gained by the offense's 3x1 formations.

With three true receivers to one side of the field and only one to the other, the defense is in a difficult position. As former Alabama defensive coordinator and current Georgia head coach Kirby Smart said of the Trips set shown above at a coaching clinic in 2013:

"We consider it a bastard formation. This set becomes an issue for us. The formation has all the speed receivers to one side and the running strength to the other. We do not want to rotate the free safety down to the weakside with all the speed the opposite way."

Stretching back to the days of Sid Gillman and Don Coryell, both of whom greatly influenced the likes of Bill Walsh and Lavell Edwards and effectively built the modern passing game as we know it today, offenses have tried to create triangles with their pass routes, giving the quarterback as quick and easy a read as possible.

Previously, the triangle was often made up by a split receiver, a tight end, and a back releasing out of the backfield. But sets with three capable receivers to already split out like these give the power back to the offense, as the defense's alignment could easily show their play-call before the ball is ever snapped.

As we'll show, however, defenses have now found countless varieties to counter sets like these in their pattern-matching Quarters systems.

Man-Coverage

The first, and most basic, approach to covering a trips set is with straight man-to-man coverage. Instead of worrying about how to trade routes from one defender to another, each player will simply declare which receiver is their responsibility and stick with him throughout the play.

As seen in the example below, though, this kind of approach can play directly into the offense's hands if they expect it. On this play, the defense is in a traditional 4-3 set with a safety covering the #2 receiver in the slot as they anticipate a run.

If the offense does throw the ball, that safety is now left on an island with no help to the outside, leaving the corner route wide open for Buckeye receiver K.J. Hill to make a play.

The Snag concept is a perfect example of the triangle stretch, as it has answers for virtually any coverage. But against man, the corner route is nearly unguardable, especially when the receiver sells the inside move first as Hill does above.

While the Buckeyes under current coordinator Greg Schiano rely heavily on this kind of man-coverage with a seemingly unending stable of talented cover-corners able to make up ground, most coordinators at the college level like to rely on other answers for three-receiver formations.

Box

The first, and most basic, way to pattern-match routes like Snag is to make a Box call. As the name implies, four defenders create a literal box around three receivers, with each defender responsible for the route coming to their corner.

Even as the cornerback gets caught looking in the backfield instead of playing his assignment in the example below, the additional defender (in this case, the safety) is there to help, double-covering the deep receiver in what Nick Saban calls a Cone technique, funneling the receiver between two deep defenders.

The only downside to a Box call is it only works against compressed sets like the one above, making it the ideal response to bunch formations. Against formations that spread all three receivers from the hash to the sideline, there is simply too much space to play a four-corners set, meaning defenses must find other ways to pattern-match.

Solo

Easily the simplest, and thus, most popular way to defend a 3x1 set is by making a Solo call from a traditional Quarters alignment. Instead of rolling defenders over to the strength of the formation, the defense stays put in their 2-deep shell while making minimal changes to the original plan.

This approach was made famous by Dantonio along with his former top lieutenant, Pat Narduzzi, now the head coach at Pitt. The most important piece of this puzzle is the weakside cornerback, who is now locked in straight man-coverage against the lone receiver to his side, which is sometimes known as what Nick Saban calls a MEG technique (Man Everywhere he Goes).

With the backside receiver taken care of, the weak safety to that side can now help his teammates to the three-receiver side, covering any vertical routes from the #3 receiver (often a tight end).

Though the Oklahoma offense had a great counter to the Solo call in the example above, the big gain was due to the linebackers failing to recognize the route, not safety Jordan Fuller. The outside linebacker didn't gain enough depth while the middle linebacker was late getting to his pass drop, leaving the safety to make up a lot of ground on a wide open receiver.

As Narduzzi told a coaching clinic in 2015, the real onus is on the middle linebacker to make the Solo call work, not the weak safety.

"The Mike linebacker keys the number-3-receiver to the trips side. He widens to the receiver and reads his pattern. If he goes vertical, the backside safety has him. The Mike linebacker walls and carries him to his zone responsibility and begins to look for inside-breaking patterns. If he gets an "in" call from the outside linebacker, he knows there is a receiver coming inside. HE drops and picks up that pattern.

"The backside safety reads the pattern of the number-3-receiver. If he runs underneath, the safety releases him and looks to the quarterback. He favors the corner and helps on inside-breaking routes."

As Narduzzi noted at the end, the true value of the Solo call is not necessarily the pass coverage, but its ability to let the weak safety read the quarterback, effectively adding an extra defender to the run game unless the #3 receiver runs vertically. This tactic proved to be the difference in the Spartans' 2015 upset in Columbus, as the Buckeye running game was never able to get going thanks to the efforts of the MSU safeties.

Of course, the weakness of Solo is the weakside corner left alone with often the best opposing receiver. But since Meyer arrived in Columbus, only Michael Thomas proved capable of consistently winning one-on-one battles like that, meaning the Buckeyes have and will continue to see plenty of Solo.

Cloud

If a defense consistently calls Solo, though, one of the weak spots is often the underneath flats, as quick receivers can often beat trailing linebackers out to the numbers. To combat this, defenses will often add a Cloud call to the mix, surprising the offense by keeping the cornerback underneath.

The concept comes from a popular adaptation to the traditional Cover-3 zone, where the cornerback and strong safety switch roles, leaving the inside player responsible for the deep, outside 1/3 of the field. The same concept is applied here and works very similarly to the Box concept, as the corner and outside linebacker pick up any underneath routes while the safeties bracket the lone deep receiver.

Since this approach often leaves the defense in a potential mismatch between a receiver and a safety down the field, the Buckeyes don't see it very often. Given how frequently they attached bubble screens and arrow routes to inside runs last fall, however, Meyer and his staff should expect to see more Cloud calls in 2018.

Special

The final wrinkle pattern-matching defenses will throw at a 3x1 set is referred to by many different names, such as Special, Mini, or Stubbie. Like Cloud, Special is an excellent counter to teams that like to attack the flats by gambling that the offense will not throw deep to the #1 receiver outside.

In this concept, the cornerback to the strongside will make a MEG call on the outside receiver, following him wherever he goes. Inside of them, though, the defense will pattern-match the remaining two receivers with three defenders, creating a triangle of their own and cutting off any high/low stretches.

The benefit to Special is it gives the defense the ability to split the field in half and play games with the weakside receiver, should he be able to beat that cornerback in Solo. The weak safety could bracket the lone receiver, read the quarterback and act as an additional run defender, or play a deep half over the top as we saw from new OSU assistant Alex Grinch while he was in charge of the Washington State defense last fall.

These are only some of the more common ways defenses can choose to defend overloaded formations with three receivers to one side, and there are plenty others we haven't covered, such as Stress (a.k.a Stump) and Clip. But though Venables and Saban have over three dozen coverages in their playbooks, they still must be able to teach them all in limited practice time, and then know when to call them on Saturdays, extending the never-ending game of cat-and-mouse between offensive and defensive play-callers.