Going back to the days of Woody Hayes, Ohio State has always sought to run the ball effectively, and the countless trees in the All-American grove belonging to running backs and offensive linemen prove it. This year's Buckeye team is no different, as the Buckeyes return not one, but two 1,000-yard rushers in J.K. Dobbins and Mike Weber, who along with unprecedented depth up front should provide a convenient safety blanket for a new quarterback and interim head coach.

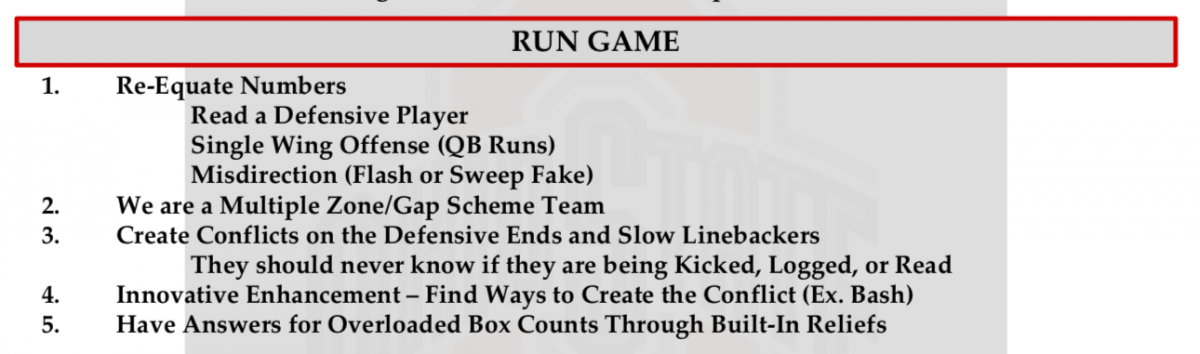

As has been the case since Urban Meyer arrived in Columbus six years ago, Ohio State will continue to showcase a pro-style running game able to create lanes both inside and outside, with both zone (block an area) and gap (block a man) schemes. Though he's most famous for using the quarterback in the run game, Meyer's teams have always put a great deal of thought into how they run the ball, as is shown on the first page of his playbooks:

To prepare you for the upcoming season, we've pulled a few pages out of the Buckeye playbook to show just how they plan on taking advantage of those talents in the backfield. Though this list is not exhaustive (the Buckeyes have around 30 individual running concepts to pull from), those below outline the vast majority of handoffs Dobbins and Weber will receive this season.

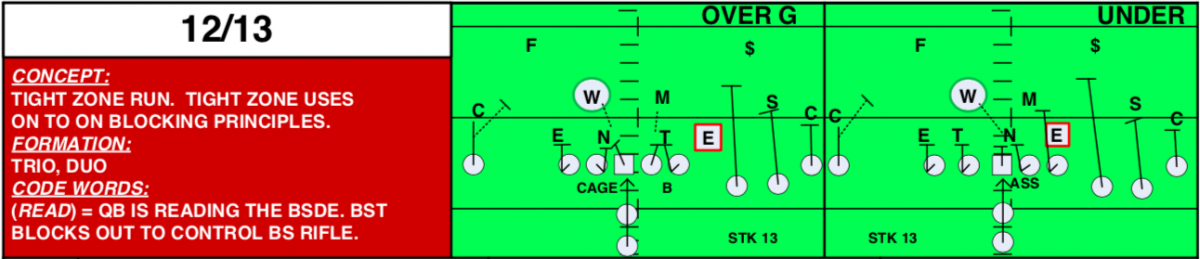

Tight Zone

Without question, Tight (often called inside) Zone remains the single most important concept in the Ohio State playbook. At its core, the play asks the offensive line to all step in the same direction at the snap, and drive the man in their gap upfield.

The most critical block is the combination between the center and a guard, as the two blockers will first double-team the nose tackle before one breaks off to take on the middle linebacker. The back will read the center to determine his path, starting with the front-side A-gap before looking for a hole along the backside of the play.

Before he ever gets the ball, however, the quarterback will read an unblocked defensive end to determine whether to give the handoff or keep for himself, re-equating the numbers in favor of the offense. If the quarterback keeps it, he can either run or identify a second defender to put in conflict by throwing a quick pass outside, known as a 'relief.'

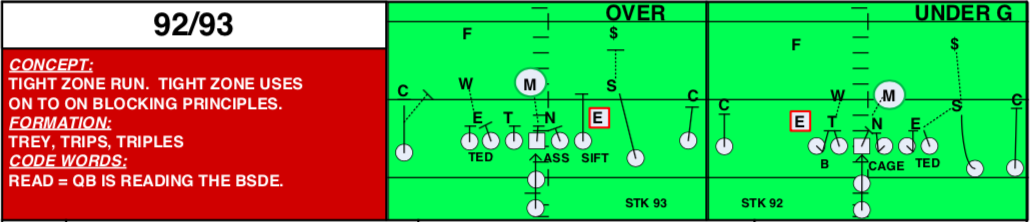

Though the concept seems simple, the devil is in the details, which is why the Buckeyes have so many variations in the playbook. As seen above, there is an iteration that leaves the end to the strong side unblocked (12/13) and one that attacks the weak side end (92/93). Though the plays are executed the same way for the line, this versatility allows the coaching staff to attack the weakest point of the defense easily.

As seen in this example of 93 above, the center reaches to get a hand on the nose immediately before getting to the second level linebacker. Then, with the unblocked end held by the threat of the quarterback run, the back sees that the blocks of the backside (in this case, left) guard and tackle will quickly close the A-gap, forcing a quick redirection back outside the tackle for five yards.

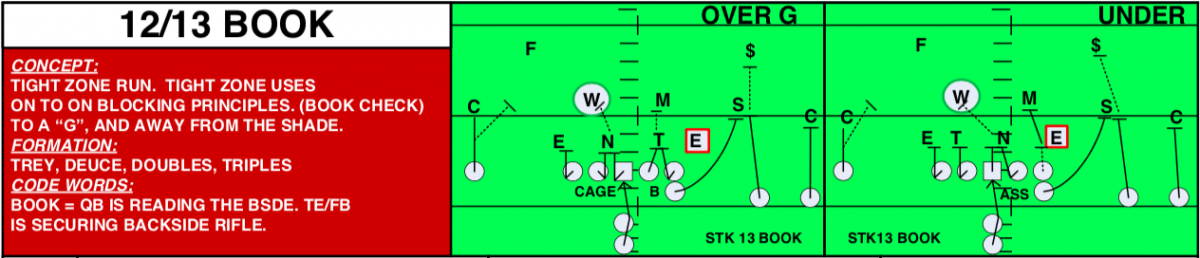

One of the best complements to the weak side tight zone read is Book, which attacks the strong side end by asking the tight end to feign a block after making initial contact and getting upfield to the outside linebacker.

Every other aspect of the play remains the same. However, the tight end's 'arc' block leads the QB through the D-gap outside, should the over-aggressive end bite on the handoff. If the end stay home to play the QB, then the offensive line has a five-on-four advantage over the other box defenders.

Though Dwayne Haskins is not expected to run anywhere nearly as often as his predecessor had, he'll still likely be asked to make these reads in short-yardage situations, keeping the defense from overplaying his talented backfield mates.

Split Zone (Crunch)

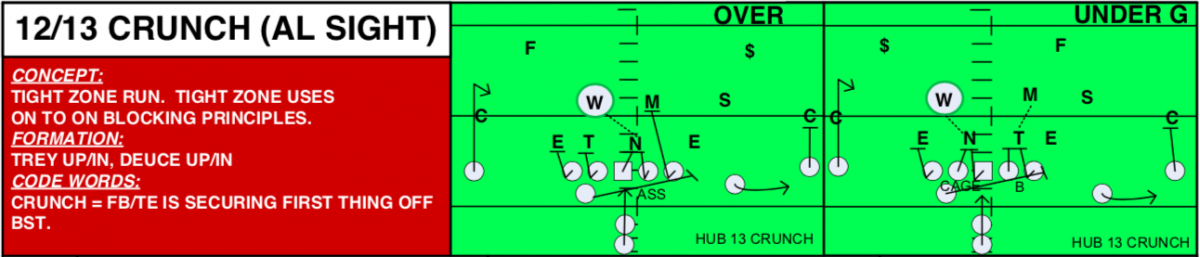

One common wrinkle to Tight Zone is what the Buckeyes call Crunch, but is more commonly known as Split or Slice. In this concept, the five linemen maintain the same, tight zone rules as noted above, but the tight end will come across the formation in his backfield alignment to cut off the backside C-gap defender.

The end thinks he's being read and often doesn't expect the block coming from across the formation, which creates a natural cutback lane for the runner.

Since the end isn't actually being read, the QB will instead watch the movements of the outside linebackers, potentially pulling the ball out to throw a slant or hitch to the frontside receiver or a bubble screen to the backside. These reads are often determined by the defender's pre-snap alignment, however - not while giving the handoff to the back.

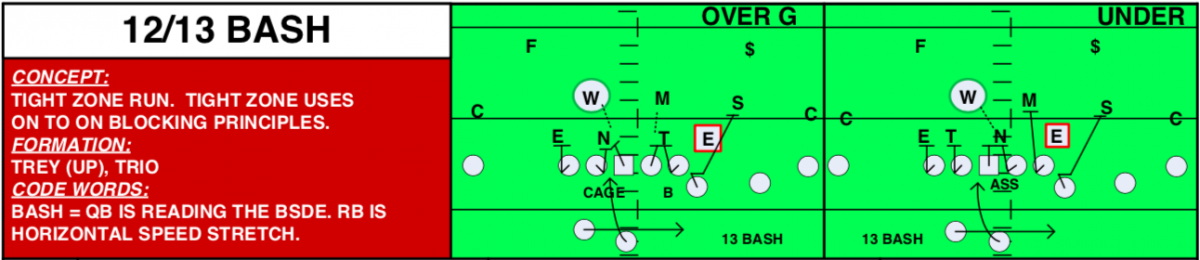

Bash

This variation also maintains the same blocking rules up front, but flips the roles of the quarterback and running back (BASH - Back Away Speed Handoff). Again, an end is left unblocked to be read, however, this time the slightest hesitation is all the back needs to run right by him on a speed sweep.

Those familiar with the old Houston Veer Option offense will find recognize this concept, as the QB often ends up hitting a gap to the same side as the back's speed sweep.

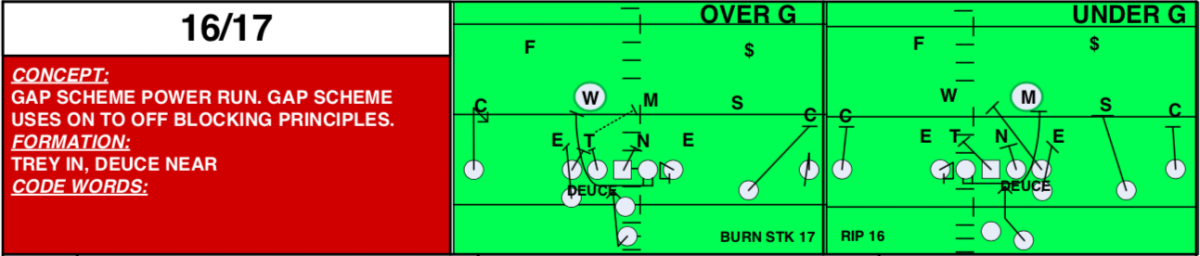

Power

The Buckeyes often pull this gap-blocking concept out of the bag against odd and under defensive fronts in which the nose tackle is creating problems for the center with his alignment. By pulling the backside guard while asking the play side guard and tackle to block down inside, the offense has a numerical advantage on one side of the formation.

Additionally, the tight end seals off the C-gap defender while the pulling guard comes tight around the butt of the tackle and looks for a second-level defender like a linebacker. To ensure there is no space between them, the puller will often shuffle down the line, keeping his shoulders square to the line of scrimmage.

Though the back's landmark is the frontside A-gap, he follows the pulling guard up through the hole and bounces inside or out based on the block.

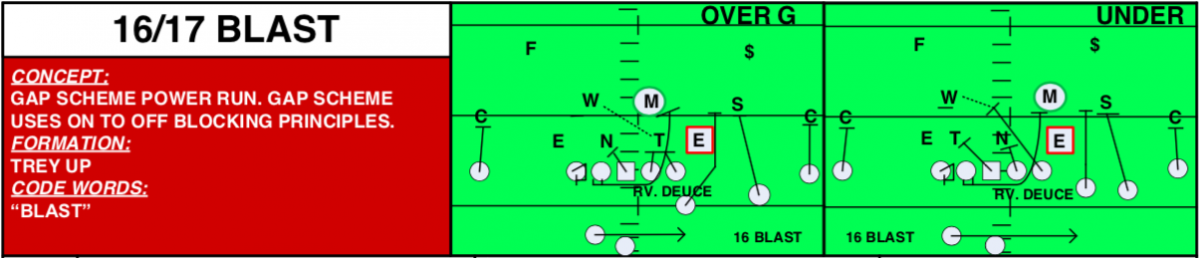

Power-Read (Blast)

This concept, known to many as Power-Read' or Inverted-Veer, marries the Bash concept with the Power blocking scheme. Like Power, the front side guard and tackle block down while the backside guard pulls around to lead upfield.

However, the quarterback will read the front side end to either handoff on a speed sweep outside or keep to run inside.

One common adjustment seen from the Buckeyes is to make the play a toss to the back who is then lined up to the front side. Though the same blocking rules apply and the front side end is still read, there is just no more handoff mesh, allowing the toss to hit outside much quicker.

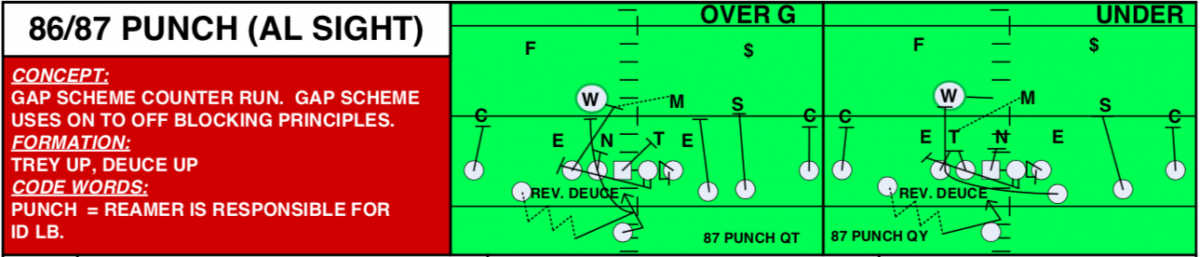

Counter

Similar to Power, Counter is a gap scheme that features a pulling guard. The big difference between the two plays is that Counter uses misdirection, taking two blockers from the strong side and pulling them back to the weak side to lead the runner.

As the weak side guard and tackle block down inside, the guard kicks out the end man on the line, opening up a gap for the "reamer" (often the tight end), to lead through the hole and seal the linebacker. There are many different variations to this concept, such as pulling the strongside tackle or running back to be the reamer, with the quarterback then acting as the runner.

Over the past few years, we've seen less and less of this concept in Columbus, as it was most effective with Braxton Miller as the runner. However, as evidenced by the 2018 Spring Game, we're likely to see Dobbins and Weber receive carries behind this blocking scheme quite often this fall.

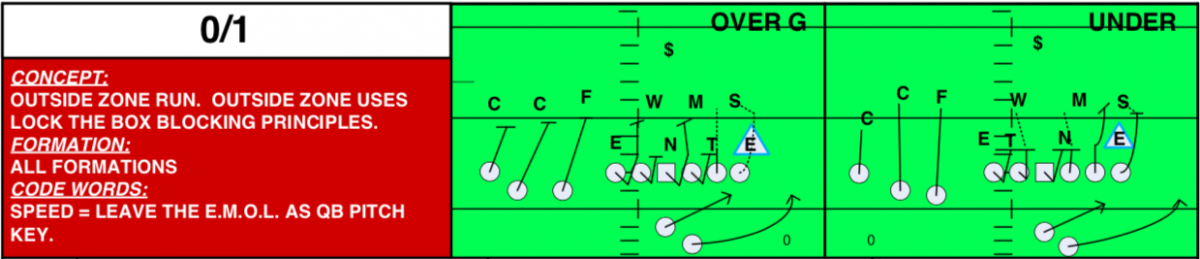

Stretch

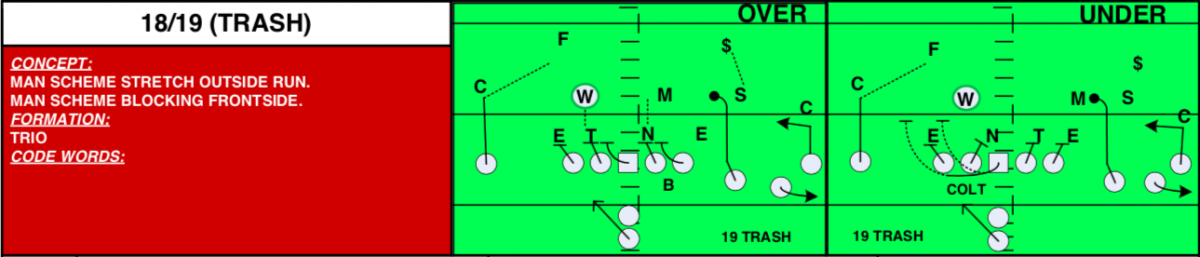

Outside runs can be executed in two ways at Ohio State, using both zone and gap blocking to spring the ball-carrier. The first method asks each lineman to take a lateral step in the direction of the play, aiming for the opposite armpit of the defender.

Once contact is made with the defender, the blocker works for width and his rules are simple: If the defender stays outside, push him into the sideline (stretch him). If he tries to fight back inside, seal him.

The back aims for the outside hip of the tackle and waits for a gap to appear. Once it does, his job is to put his outside foot in the ground and explode directly upfield.

However, if there is a defender lined up inside one of the play-side blockers, that blocker will simply block down and seal the defender inside immediately, never taking the lateral step outside. Then, the blocker next to him will make a "Colt" call and loop around the down block in what many call a 'pin & pull' scheme.

The most famous example of this play came four years ago. You may have seen it before.

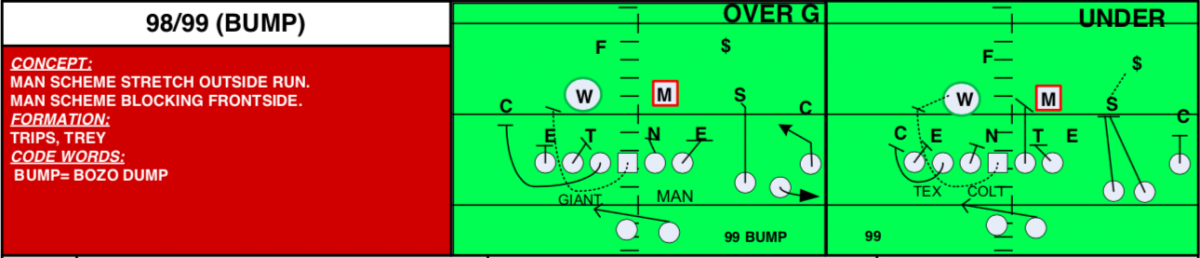

However, as mentioned above, the Buckeyes can execute a similar stretch run with gap-blocking principles.

Often referred to as a Buck Sweep, this concept asks the play side linemen to identify the location of the defensive tackle. If the DT is in the B-gap, they'll make a "Giant" call and the tackle will block down inside while the guard and center pull around him. If the DT is in the A-gap, the tackle and center will pull while the guard blocks down.

The back's job is to go flat down the line of scrimmage and follow the second puller through the hole.

Speed Option

The final play isn't seen often and is one of the most basic in the playbook. Ohio State's speed option utilizes the outside zone blocking described above, though there is no option to make a "Colt" call here.

The end man on the line is left unblocked so that the QB may read him for the pitch by attacking his outside shoulder. If the optioned defender closes on the QB, the running back should be five yards wider and one yard deeper, allowing him to catch the pitch in stride.