You didn't need to be a coach or scout to see it.

Diagnosing some of Ohio State's offensive tendencies through the first three games of the 2023 season has not been difficult. Even the least scheme-savvy among Buckeye nation have begun to notice their favorite team's fondness for running the ball toward the short side of the field, known colloquially among football-knowers as 'the boundary.'

This desire to run that way is due, in large part, to the wider hash marks in the college game (compared to the NFL), and the manner in which defenses respond by aligning more defenders to the wide side of the field. Given that there are an odd number of players on the field, college and high school defenses rarely place the extra body on the boundary side, electing instead to place him in an area that allows the entire unit to cover space more evenly.

This is one of biggest differences between this sport and its professional counterpart, where defenses often match the formation strength of the offense with the ball sitting between tighter hashes.

If you are calling plays for a college offense, then, you can be easily tempted to run toward the boundary as there is often one less defender to block. Ryan Day and his staff, it would seem, submit to such temptation on a regular basis.

This is not a new inclination, either. In recent years, the OSU run game has featured a heavy dose of outside and mid-zone runs in the direction of the nearest sideline, though its usage has seemed rather acute this fall.

While the team was not completely unsuccessful on the ground against Indiana and Youngstown State, averaging a mediocre 4.6 yards per attempt, it did not inspire the high level of confidence typically required by the OSU faithful. Some of that could be pinned on the apparent lack of chemistry along an offensive line featuring three new starters, but many (this writer included), began to wonder aloud about the play-calling.

Yet in the third week of the season, the run game proved far more successful, tallying 204 yards while averaging over six yards on each attempt. This improvement didn't come as a result of changing the scheme, but rather by doubling down on it.

When watching TreVeyon Henderson's highlights from Saturday, you still see a whole bunch of outside zone runs (otherwise known as Stretch to many) into the boundary. His first three carries came on variations of the same play, including what would be the first of many touchdowns for the team clad in scarlet that afternoon:

The offensive line certainly deserves some credit for this upgrade in the ground game, as they look far more comfortable identifying and executing the combination blocks required in zone-blocking schemes. But this was not entirely the result of improved technique.

It's quite likely that Day and his offensive staff leaned so heavily on this concept due to the way in which their opponent defended a version of it.

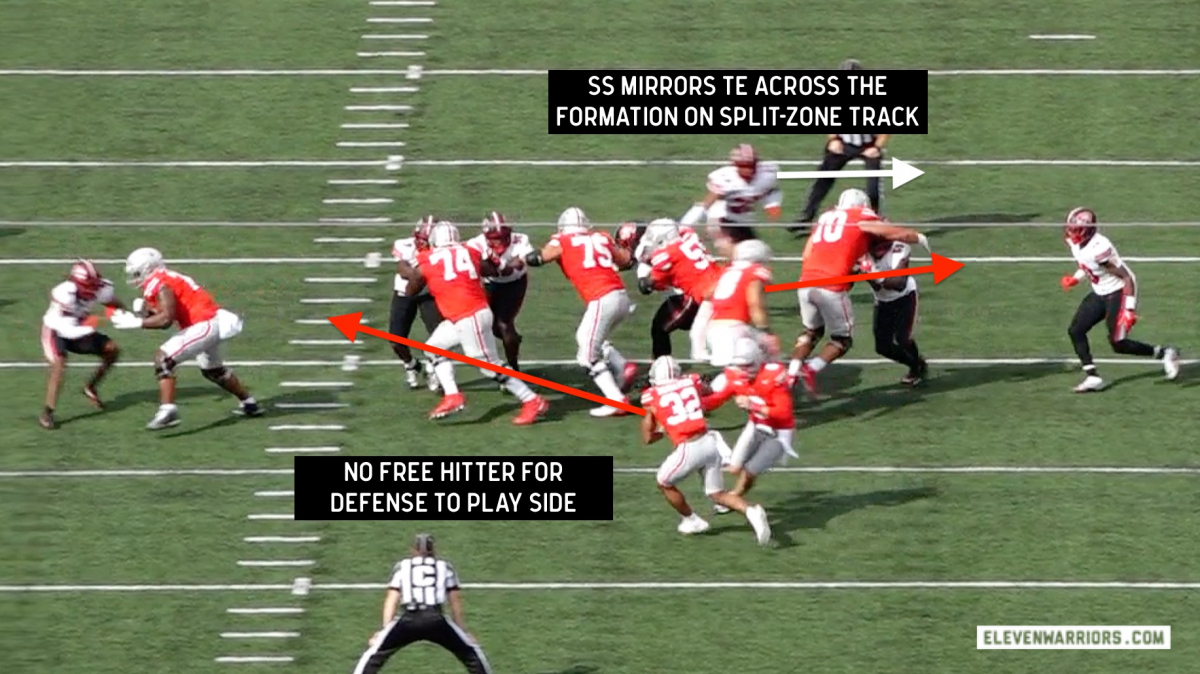

In an effort to keep the backside edge defender from chasing down these zone runs, an offense will occasionally send a tight end or fullback back across the formation to seal this edge defender. This action, known as 'split-zone' to most but called 'Crunch' in the Ohio State's lexicon, not only allows the ball carrier more time to wait for his blocks to develop without fear of getting caught from behind, but it can also create a cutback lane for the runner.

In an effort to take away such cutbacks, as well as account for any play-action passes built upon this action, the Hilltopper defense would lean heavily on man-coverage concepts that mirrored the path of the tight end with a linebacker or safety. This defender would follow the path of the tight end away from the rest of the action, leaving the defense with one less body to block toward the boundary.

This was not just something the Buckeyes took advantage of on the first drive, either. They continually spammed the WKU defense with this same run concept throughout the day. On each occasion, the tight end dragged a defender away from the ball while attempting to block another, creating wide-open lanes for Henderson and Chip Trayanum to run through.

The Buckeye offensive line would mix between two variations of zone-blocking: outside and mid-zone. The two can look very similar, even to the trained eye, but the subtle differences can lead to big outcomes.

Rather than simply drive straight upfield as was the case in Urban Meyer's tight-zone runs, which aimed to hit the A-gaps on either side of the center, outside-zone runs ask the line to move horizontally. The first two steps for each lineman are lateral, with the runner looking to get the ball outside the tackles. Mid-zone is exactly what it sounds like, with the line's first step being at a 45-degree angle while the runner aims for the outside hip of the guard.

Of course, the beauty of zone blocking is that it allows the back to choose his running lane in real-time, rather than aiming for one spot only. The ball carrier can either stay on his original path, bounce it outside, or cut back inside based on how he reads the defense.

While Henderson's elite speed allows him to bounce the ball outside and around the corner, making him an excellent candidate for outside-zone runs, Trayanum's more physical style is better suited to life between the tackles. Thus, when he entered the game, the Buckeyes called for more mid-zone, though also with that same Crunch action from the tight end.

As Cade Stover came across the formation to seal the backside end on Trayanum's fourth carry of the day, the defender assigned to Stover (#31) failed to fill the cutback lane. Before he knew it, 234 lbs of Summit County speed came thundering through his run gap, and 40 yards later, Trayanum was in the end zone for his first career touchdown in a Buckeye uniform.

Right now, you might be asking, 'Why would that defender be so worried about Stover on that play?' On the surface, it's a fair question. But when looking at OSU's game plan as a whole, it's easier to understand how such poor gap discipline could come about.

In addition to running outside-zone toward the boundary on the game's first drive, Day and Co. attached a number of reliefs to those concepts, giving quarterback Kyle McCord the option to quickly throw the ball the other way based on the defense's pre-snap alignment. These are similar to RPOs, however, Day differentiates between the two as reliefs are a pre-snap decision while true RPOs require the QB to read the defense's movements only after the play has begun.

These reliefs often take the form of screens and one-step hitches or slants to the receivers away from the run action. Against WKU, the Buckeyes unveiled a tasting menu of reliefs for the Hilltoppers to consume, often using Stover as a lead blocker away from the path of the running back.

On just the third snap from scrimmage, Ohio State sent Emeka Egbuka on the split-zone path away from the handoff, giving McCord a veritable triple-option with the star wideout acting as the pitch man outside. The Hilltoppers did not follow him across the formation the way they would with Stover the rest of the game, and got burned for a big, early gain.

As the first half progressed, Ohio State had amassed a huge lead and the Hilltoppers finally gave up on their plan of mirroring split-zone action. So, as soon as Day knew Stover wouldn't have anyone following him across the formation, the Buckeyes called for a play-action rollout that found the tight end wide open in the flat for yet another big gain.

Defending such a game plan can leave defenses with very few good answers, something Marcus Freeman noted this week in his weekly press conference.

“You’ve seen their offense kind of evolve over the first three games," the Notre Dame head coach said ahead of Saturday's marquee matchup in South Bend. "It all starts with the run game. They want to run the ball. Very similar mindset to what I have: The ability to run the ball will create openings in the pass game.”

Building confidence and instilling some rhythm in an offense that seemingly lacked both was surely a big reason why Day continued to utilize so many wrinkles against an overmatched opponent. But giving the Irish a full menu to prepare for can be just as effective as holding back something new, forcing the defense to dedicate valuable practice to concepts that may never be seen again.