It's not just a short-yardage issue.

Ohio State is 5-0, coming off a 20-point victory over a previously undefeated Big Ten opponent, ranked third in both major polls, fourth in SP+, and ranks in the top 10 in both yards and points allowed. If you had told me ahead of the season that supporters of the Scarlet and Gray were freaking out right now, I would have surely shaken my head and spewed some four-letter words about the fanbase's unrealistic expectations.

As regular readers of Film Study will (hopefully) tell you, we try to be objective in this space, taking the hot air out of many arguments and providing calm-bordering-on-sterile analysis.

...

But the Buckeye run game is a real problem.

Despite all the lofty rankings listed above, one that can't be ignored is the fact that just four teams in FBS have fewer runs of 10+ yards than Ohio State does through nearly half the season.

Questions arose after underwhelming performances against Indiana and Youngstown State, but gaining 204 rushing yards on Western Kentucky seemed to show that an offensive line with three new starters had found some chemistry. One week later, TreVeyon Henderson's 61-yard touchdown run overshadowed an otherwise disappointing night on the ground, as the visitors averaged just over two yards on all other carries inside Notre Dame Stadium.

It was a Maryland run defense that now ranks 27th nationally which showed that not only does Ohio State still have issues running the football on 3rd-&-1, but on 1st-&-10 as well. The Buckeyes probably didn't expect to have so much trouble running on a unit that surrendered 4.3 yards per carry to Towson in its season opener, even without Henderson in the lineup.

But the Buckeyes didn't tally just 62 yards on 33 carries because Chip Trayanum was the starter. Rather, it was a fundamental issue with the blocking that allowed the Terps to erase almost every one of his attempts.

Most OSU fans know that the run game is built around wide and mid-zone runs, aiming to hit the C or D gaps with a chance of cutting the ball back inside when the defense overplays the scheme. But while zone-blocking theoretically allows any play to be successful, given its simplicity, it only works when the players execute it properly.

Against Maryland, that simply wasn't happening.

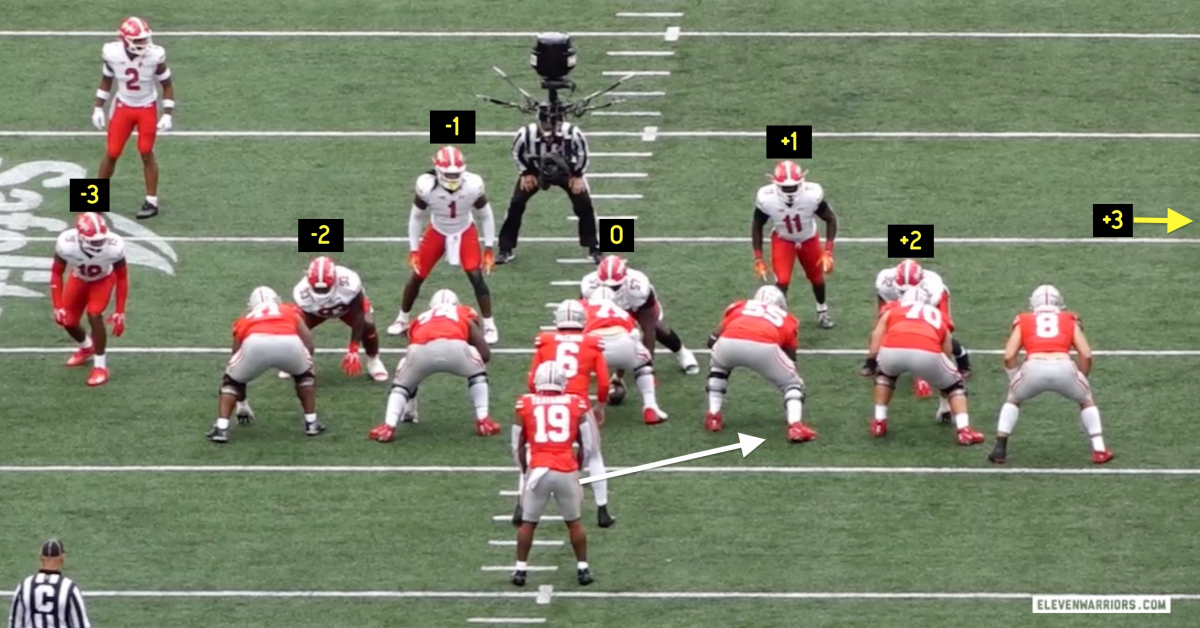

Ryan Day and Justin Frye are both noted pupils of Chip Kelly, who has long taught zone-blocking to his linemen by assigning numbers to defenders rather than learning countless defensive fronts. While it's not confirmed that this is still being taught inside the Woody Hayes Athletic Center in 2023, there's little reason to believe otherwise.

In this system, the center identifies the player for which he will be responsible and assigns him the number 0. From there, the play-side guard's man becomes the next defender outside, regardless if it's a down lineman or a linebacker, and gives him #1 while the tackle takes #2, and the tight end #3.

While all the linemen take the same three steps at the beginning of each play, the blocker(s) responsible for taking on a linebacker typically start climbing to the second level on their fourth step. All too often against the Terrapins, however, the linebackers were left unblocked as the offensive line continued to double-team down linemen, allowing Trayanum to get swallowed up at the line of scrimmage.

Most concerning of all is the lack of movement that was generated up front, despite two players constantly staying on double teams. Far too often, a Maryland defensive lineman fought two OSU blockers to a stalemate, refusing to give up ground thanks to superior leverage against the taller Buckeyes.

This technique of working in pairs to properly execute a combination block against two defenders is not exactly novel. Generations of offensive linemen have mastered these relatively basic combinations, making it all the more perplexing that the Buckeye offensive line can't seem to work to the second level.

Luckily, no one seems to be more aware of this problem than Frye, himself.

“We have, just in general, our room here at Ohio State, we have a very high standard," he told reporters last night. "So you’re always chasing that. You’re always pushing to that. So are we there yet? No.”

To be clear, this is a weekly column dedicated to the analysis of Ohio State football schematics, and in this instance, we here at Film Study have no qualms with the reliance on zone-blocking schemes. Their execution, however, is a very different story.

As shown in the first image above, the Buckeyes had the adequate number of blockers needed to neutralize the seven defenders near the line of scrimmage, as Kyle McCord's bootleg action is meant to hold the backside end. But Chip Trayanum didn't fail to pick up yardage because there were too many defenders, but rather because his blockers simply didn't block the right ones.

What's more frustrating is knowing that this group can, in fact, execute zone schemes properly and block these linebackers at the second level:

The GOOD news: These guys got a lot better and avoided duplicating mistakes as the game wore on.

— Kyle (@Jones) September 4, 2023

Watch them run stretch into the boundary in 2Q. The center, Hinzman #75, puts on a clinic in this rep, working with 74 to cut off the NT before getting to the WILL quickly and pic.twitter.com/ps3bFdWwWV

As the game wore on, Day and his staff began employing a multitude of tactics meant to divert those linebackers long enough to spring the runner, knowing the offensive line wasn't getting to them. But motioning a tight end across the formation was only enough to buy time for Trayanum to eke out a five-yard gain before the distracted defender recovered to make the tackle.

Given the unit's struggles while running zone schemes, the coaches naturally called for Counter plays, which are a better fit for Trayanum's running style, anyway. But yet again, he was met in the hole by Maryland defenders as both tight ends at the point of attack failed to execute their blocks.

Those blown blocks meant the pulling guard and tackle had to take on the two edge defenders, meaning no one was able to block...you guessed it, the inside linebackers.

The only real bright spot for the running game last Saturday was the use of a rarely seen concept in Day's playbook, but one which has found quite a bit of success at the professional level recently: the crack toss.

The scheme is a variation of the regular outside zone in which the outside-most blockers block down (rather than outside) and use the natural leverage that comes from blocking at an angle to pin the defender inside. Meanwhile, an interior blocker pulls around the edge to lead the runner.

Not only did Trayanum find the end zone with this concept, but he rattled off an eight-yard gain on the first snap of the following possession when Day called for it again.

But crack toss is unlikely to replace the base mid and outside zone plays as the foundational element of the Buckeye run game. Thus, it's important to identify why those schemes failed so miserably against the visiting Terps.

There could be a number of potential reasons why the Buckeye offensive line struggled to get its hands on the Maryland inside 'backers at the second level.

For one, the Buckeyes prefer outside and mid zones to the inside version as it allows the blockers to stay close enough to the line of scrimmage to run longer-developing run-pass options (RPOs) without garnering a penalty for having an ineligible man downfield. But in both examples above, there was no pass option for Kyle McCord as the receivers were all blocking, so that excuse is rendered moot.

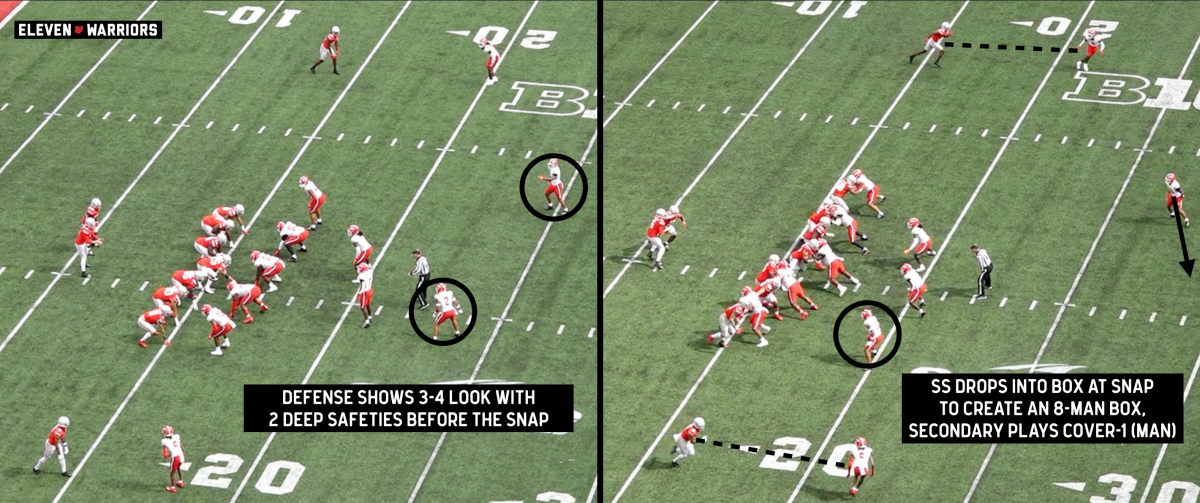

Perhaps, then, it was Maryland's commitment to a 3-4 defensive scheme that played more like an old-school 5-2 or even 5-3 look when the strong safety rolled down at the snap:

“(Maryland) played that 3-4 Okie front a little bit," Frye said of the Terrapins' preferred alignment on Saturday. "So getting movement on that first level and how many guys move down – when you look at that, a lot of our play-action stuff hit because those guys were down. So it’s a give-and-take. But yes, we’ve got to be more explosive on those ... getting the ball to that second level and working that.”

But seeing an odd front shouldn't have been that much of a surprise, as the Terps had shown it throughout the season on film, allowing the Buckeyes ample time to prepare. Perhaps, more than anything, the issue is not who is in the huddle or on the sidelines, but rather, who isn't.

The Buckeyes became far more dependent on outside zone schemes beginning in 2017 upon the hiring of Day and Kevin Wilson to reinvent a stagnant attack. Wilson is considered a guru of zone blocking, having sent countless running backs and linemen to the NFL as a result of his efforts at Northwestern, Oklahoma, and Indiana, leaning heavily on the scheme at each destination.

Frye, meanwhile, has obviously coached the scheme throughout his career, but when he and Day first worked together at Boston College a decade ago, the BC ground game was based far more on gap schemes like Power-O. Though he came to OSU after working directly with Kelly in Westwood, the UCLA running game has been known for its diversity in recent years, rather than a reliance on any one scheme.

It's not as if the players themselves aren't capable, though. Despite the run game struggles, the OSU offensive line has been solid in pass protection, with five of its seven sacks allowed this season coming on plays in which McCord simply held the ball too long.

But unless Day, Frye, and the rest of the offensive staff show they can fill the gap left by the loss of Wilson and his decades of experience, no amount of effort will make up for what plagues the Ohio State running game at this point. While this Saturday's opponent, Purdue, ranks just 85th in the nation when it comes to stopping the run, Penn State and its sixth-ranked such unit is looming on the horizon.