I was the little red dot floating in the middle of a bright orange sea.

Illinois had finished its 1999 season throttling everything in its path. This included the Buckeyes in Ohio Stadium on Senior Day by 26 points, and then Virginia in its bowl game by a score of 63-21. Illini fans were understandably excited. The school sold a whole bunch of football tickets heading into the following season.

So infiltrating those premium, center section seats of Memorial Stadium would be challenging for any fans back in 2000, let alone the visiting ones - but there I was, that little red dot - quietly seated inside the wave with my face resting in my gloves.

There were three seconds left. Ohio State and Illinois were tied at 21.

Dan Stultz was lining up to attempt his fourth field goal and ruin Illinois’ Senior Day, 364 days after the Illini had wrecked Ohio State’s. That was also 364 days after I first met my then-girlfriend at the Varsity Club prior to that terrible game. She was a lifelong Illinois fan who had traveled to Columbus to see her team play. We had shared a few cold Jägermeisters on the back patio and hit it off.

Early in the quarter Illinois QB Kurt Kittner was knocked out of the game by a vicious shot to the head from Mike Doss, who would have been immediately ejected had today’s safeguards been in place. The Illini were listless with him gone. Stultz, who had already missed a PAT and had a maddening habit of delivering low, knuckleball kicks was lined up to win it. He was perfectly still. The orange sea all around him was not.

“Congratulations,” he muttered in disgust, smiling.

The ball was snapped and Stultz dropped the ball right between the uprights from 34 yards out to win the game. That gregarious orange sea abruptly fell silent and still. Stultz, Ohio State’s only hyper-celebratory placekicker of the current century immediately went nuts, just as he would have for a 34-yard 1st quarter field goal.

As the ball left his foot my face jumped out of my gloves and I sprang out of my seat. The Buckeyes poured onto Illinois’ field in celebration, now in position to win a share of the Big Ten title against Michigan, which one week later they would fail to do. I triumphantly held my fists in the frigid air for several seconds before realizing I was the only person standing up in the entire section.

Scanning my surroundings - fists still raised - I was the only person standing up across several sections. The invisible continuation of the 50-yard line would have split me in half. I was the little red dot now bouncing right in the middle of a sullen orange sea.

I lowered my arms and glanced down to the gentleman still seated to my left, who had smuggled me into those premium, center section seats. He was my future father-in-law, and I was then his daughter’s boyfriend, hailing from Columbus, Ohio with no chance whatsoever of being converted into a fan of the home team whose fans surrounded me.

Jim looked me up and down in my exuberance and smiled silently. I would eventually accept that this was his resting facial expression toward me. In future years I would see him absorb Illinois football and basketball losses far less graciously, although still gracious. He never lost his cool.

“Congratulations,” he muttered in disgust, smiling.

Seven hundred and thirty-four days later my now-wife and I were staying with my now-in-laws at their home in Central Illinois for the weekend. Jim was excitedly describing the restaurant where we would be dining that Friday evening in Champaign.

“You’ll love this place,” he said, “they let you cook your own steak!” Sounded good to me. I love cooking my own steak. I did it all the time on my own balcony in Chicago, sometimes without wearing pants and always without going through the trouble of putting on a pressed, collared shirt.

“So it’s a restaurant where they make you prepare the food?” I whispered to my wife. “That kind of defeats the purpose of going out to eat, doesn’t it?”

She rolled her eyes at me. I have accepted this is her resting facial expression toward me. “He’s excited to show it to you. He likes showing you stuff. You don’t hunt or fish with him. That leaves sports and food as the stuff you can enjoy together.”

Another bright orange sea trickled out of the stadium in disappointment.

We went to the restaurant and I ordered an oversized ribeye. The waiter brought it out to me, raw, along with some unbaked garlic bread. Jim and I walked our steaks over to a fire pit and laid them and the bread down on the grill. We then stood next to each other and watched our steaks cook.

“Pretty cool,” I said to him as we listened to the satisfying, ambient sound of our dinners searing. “Thing is, if I overcook this I’m sending it back and demanding to talk to the manager about how lousy the chef was. Like, you should fire that guy. Tonight.”

“We'll never eat here again,” he said snickering, “as long as this guy works here."

The following afternoon I occupied the same seat in Memorial Stadium from where I witnessed Stultz' game-winner. The Buckeyes won another thriller; this edition coming in overtime to go 12-0 on the season. The defending Big Ten champions had ruined Ohio State’s Senior Day again 364 days earlier, and another bright orange sea trickled out of the stadium in disappointment.

Three hundred and nine days after playing in the Sugar Bowl the Illini would be staying home for the holidays. Nothing would ruin Ohio State’s season that year. And nothing ruined that steak either. However, my chef from the previous evening never worked there again.

“Congratulations,” Jim muttered again toward me over dinner that night, smiling. We were in another one of Champaign's finest restaurants. The kind where they cook the food for you.

My visits to Central Illinois are generally scheduled around holidays or football games.

Since I don't hunt or fish - and my palate thanks all of you who catch and process fresh food on my behalf - I spent years bonding with my father-in-law over two things; sports or eating. Aside from his daughter that's about all we had in common, so oftentimes whenever he would get in his car to run an errand in town I would get off the couch to go with him.

As he would drive he'd talk about the Cubs, Bulls and Bears. I would listen. It's never intended to be a transactional conversation. We were on his turf and I was the audience, so I paid attention. The town is called Tuscola. It's a small town's small town. It's tired but scrappy; it reminisces about what Main Street used to be like and relishes what it might someday become again.

What I immediately noticed driving around Tuscola with Jim as he talked about his beloved professional teams was that his left hand would repeatedly raise and lower as he spoke. Every time we passed a car or a pedestrian he waved. Everyone always enthusiastically waved back at him. Male, female, old, young, on foot, standing in the yard or behind the wheel. Hello. Hello!

"Do you know everyone here?" I interjected once, driving along Prairie Street which is a road bordered by a cornfield, a church, the high school and the cemetery. "It seems like you do."

"Oh, I'm just saying hi," he said.

Every time we passed a car or a pedestrian he waved. Everyone ENTHUSIASTICALLY waved back. Every time.

I was curious to see if this was just that generally-accepted small town friendliness where everybody exchanges pleasantries or if Jim truly knew everyone in Tuscola - so I began paying attention and found there was nothing even close to a standardized greeting in the local culture.

I've been back dozens of times, over more than that many years now. There's still exactly one person whom I've seen embrace that generally-accepted small town friendliness at literally every opportunity.

"You're basically the mayor," I told him. "You're never leaving here. You can't."

He looked at me as if Stultz had just kicked another game-winner. "You've met the mayor," he replied. He was right. The mayor had attended our wedding in Chicago, because of course he was friends with the mayor. You're only proving my point, Jim.

For me the passenger seat of his car was transformed into the edge of the couch next to his recliner in the living room, where Jim seized many days of his retirement reading the newspaper - the kind that leaves ink on your fingertips - and watching hunting and fishing shows. The edge of that couch was like riding shotgun. When his hunting and fishing shows were over he would pass me the remote.

It was less of a courtesy than it was a test. Choosing the wrong channel might have sent him out of the room. Choosing the right one - a sport involving a ball, usually - and he would stay put. Then he would peel off the sports section from his smudged local newspaper and hand it over as a reward.

My OCD normally demands that I read a newspaper from front page to back page in the order that it was constructed, but when Jim hands over the sports section you accept it as-is.

That was just his language. It's a father saying hi to a son-in-law who doesn't fish or hunt. I always waved back, enthusiastically.

One hundred and ninety-two nights ago the 87th Academy Awards were held on Sunday, February 22. Former Ohio State student, rabid Buckeye fan and Scarlet and Gray Days narrator J.K. Simmons, as expected, took home the award for Best Supporting Actor for his memorable turn in Whiplash.

His acceptance speech was spontaneous, poignant and contained the following directive:

Call your mom, call your dad. If you're lucky enough to have a parent or two alive on this planet - call them. Don't text, don't email - call them on the phone. Tell them you love them and thank them and listen to them for as long as they want to talk to you. Thank you, mom and dad.

Simmons had lost his father while Whiplash was still in theaters. His mother had preceded her husband in death just two years earlier, so Simmons went from having both of his parents to having neither in less than 24 months. He had just reached the top of his profession and was unable to share the moment with either of them.

His speech was as unrehearsed as it was heartbreaking. Simmons was given a two-minute nationally televised pedestal and he used it to instruct his audience to call their parents, while they still could.

Right around the time Simmons was accepting his award my cell phone rang. It was my brother-in-law calling from an Illinois hospital. He said a lot of words on that call describing what had happened but the only ones I can still remember were he didn't make it. Words like that echo in your memory forever. The tone, the awful warm rush in your body and then the silence.

That's how you find out. It's a moment you have no control over. He didn't make it.

You're never leaving here. You can't. I had said those words to Jim all of those years ago about Tuscola. Even if my intent wasn't to be condescending, the middle of nowhere can mean everything to the people who inhabit that space. That's home.

Home is to be defended the same way I aggressively defend Columbus, Ohio - the town that shaped me into who I am today. The town I still refer to as The Pearl of the Midwest when lovingly describing it to outsiders. The town I haven't permanently lived in since the 1990s. I loved Columbus. I still love it. I just couldn't stay for a multitude of reasons.

You're never leaving here. You can't. Yeah, Jim could have left numerous times for a multitude of reasons. He just chose not to, which did two things - it made Tuscola the most important place in the world and it made him a favorite son; the kind that everyone affectionately waves at when he's around town.

Jim rests in that cemetery on Prairie Street by the high school across from the cornfield. Everyone who enters Tuscola from the highway has to pass right by it in order to enter town.

That's where he is. You might as well wave back.

Jim got to see the Horseshoe once (it was the least I could do for all of those prime seats he gave me to see Ohio State play in Memorial Stadium).

As is our custom in Columbus with first-time college football visitors, I was as patronizing as possible regarding what he would be experiencing that afternoon in comparison to what he was accustomed to in Champaign. It was a perfect September Saturday against the Ohio Bobcats. The Buckeyes were #2 in the country. We had tickets for Ohio's largest outdoor cathedral.

Prior to kickoff I showed Jim all of the campus sites that capable hosts are supposed to show their guests before heading to the Varsity Club for pre-gaming, specifically to point out the spot where I first met his daughter. I never stopped talking on that tour. He listened. It wasn't intended to be a transactional conversation. Jim was on my turf and he was the audience, so he paid attention.

The middle of nowhere was everything to him. There was nowhere else he would rather be.

While we stood on that spot at the VC I retold the story from that fateful afternoon 3,962 days earlier when Illinois had clobbered Ohio State, and I had met my future wife.

"Jägermeister?" He asked rhetorically, with a tinge of disappointment.

"That's how the kids did it back then," I replied. "Standard operating procedure."

"So you'll always come back to this spot," he said. I looked at him as if Stultz had just kicked another game-winner.

We made our way into the stadium and I explained the arrangement Ohio State football had with the other in-state schools that visit annually to fill out the non-conference schedule in exchange for millions of dollars staying within Ohio's university system. The relationship is fraternal, understood and lacks any real animosity. That's what I said.

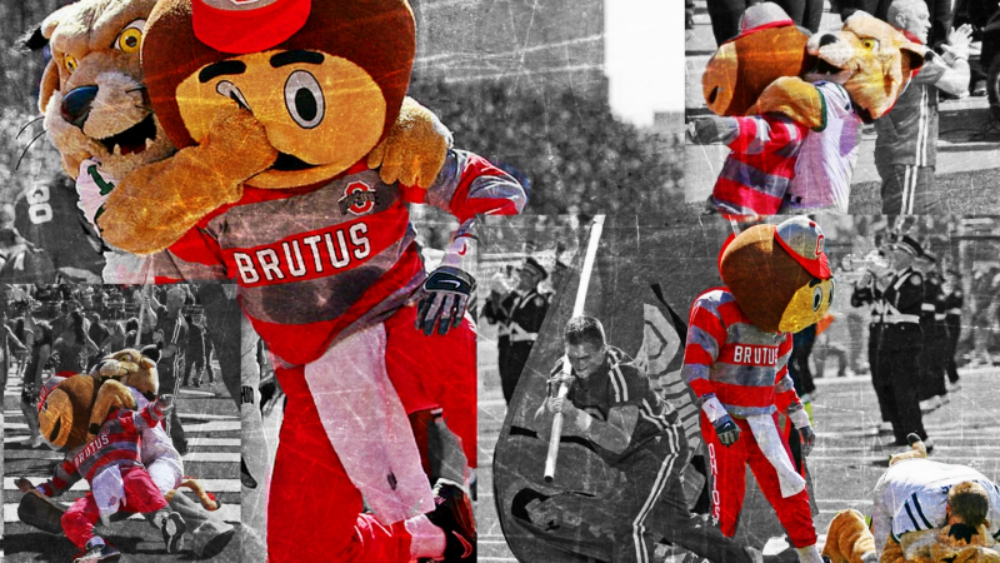

Minutes later Rufus the Bobcat ambushed Brutus at the 30-yard line and then again in the north endzone while players were on their knees praying. Everything I had just said about fraternity between Ohio state schools sounded contrived. I was no longer a credible guide.

Over the next few hours we got to enjoy something we had never shared before: Ohio State winning a laugher. Every other time we had seen the Buckeyes play together Illinois had given them fits. The lack of game tension led to conversation about other topics; I asked him where he wanted to travel in his retirement, places he wanted to see, cities he wanted to go to.

He had trouble answering. There were some waters he hadn't fished yet and that was about it. None of the usual suspects as far as bucket list places that he had to see.

I didn't say anything, but it was bewildering at the time. Retired, financially secure and yet choosing to stay in the middle of nowhere in lieu of traveling. His disinterest in seeing new places rivaled my distaste for activities like hunting and fishing. We didn't get each other but we never stopped trying to understand each other.

I'm confident Jim had already figured out that he wouldn't be able to figure me out. I eventually landed on the concept that Jim's bucket list destination was the place he knew best; where he raised his family and knew everybody in town. Why should he bother with other places? The middle of nowhere was everything to him. There was nowhere else he would rather be.

Dropping push pins all over a map of the world was not who he was. Jim only needed one pin.

The Buckeyes play Illinois on November 14 this season. That's 5,481 days since I first was that little red dot floating in the middle of a bright orange sea. The Illini are tucked between Minnesota and both of the Michigan schools in November. It's easily Ohio State's fourth-most anticipated game of the month.

College football schedules are made out years in advance and people like me - and probably you too - look at them, years in advance. Ohio State always hosts Michigan in even years and visits in Ann Arbor in odd ones. Notre Dame shows up in the next decade. There are only 1,109 days until the Buckeyes play at TCU. Our unelected next-president will be dealing with midterm elections then.

Those schedules are just dates and places; stadiums and colors. We fill those dates with people and experiences. Perhaps it's you alone on your couch, or maybe you're the fan to whom the season matters more than it should - and you travel with the team, dropping push pins all over a map of the stadiums you've visited. It's your life and you get to choose. You're the mayor.

Jim won't hand me the sports page from his recliner or graciously mutter his congratulations toward me this season - and that sucks. If I learned anything from him it's that leaving things undone is all relative. Do exactly what you want to do and go exactly where you want to go. Every single day counts, which is why I go through the trouble of counting them now.

Just don't leave anything unsaid. And never pass on waving at people you know.

So call your mom, call your dad. If you're lucky enough to have a parent or two alive on this planet, call them. Don't text, don't email - call them on the phone. Tell them you love them and thank them and listen to them for as long as they want to talk to you.