Former North Carolina defensive end Beau Atkinson commits to Ohio State.

Well, that was a pretty good game to end the year on, even if it wasn’t quite the ending a lot of us hoped for. I also hope that everyone’s enjoying the start of a new year, and I’m hoping this year is a good one for everyone.

Now this week, we’ll take a look at Jourdan and…

Get on with it!

Sorry? I…

Get on with it!

I guess that’s fair. The Battle of Hoscht isn’t all that interesting, and it’s kind of hard to explain. And I suppose we’re all really here for the real show anyway. So, It’s time to get the ball rolling with Napoleon Bonaparte, and his first independent command in the Italian campaign of 1796. But, first, let’s talk about the general’s earlier career, and the Italian theatre of the Revolutionary Wars before 1796.

Napoleon and Italy

Napoleone Buonaparte came into the world in Ajacco, Corsica, in 1769 shortly after France took the island from the Genoese Republic. His parents were minor nobility in Corsica, which made the minor nobles from the middle of nowhere, as far as their position in broader France went. They were prominent enough that Napoleon’s father attended court on behalf of Corsica in the 1770s, and his father was able to secure an appointment for his rather bright son at the Ecole Militare in Paris. Napoleon wasn’t prominent enough to secure a commission in the cavalry or infantry, so, he entered the artillery. The artillery was considered a technical branch, and so was open to nobles and non-nobles, so long as they could handle the math. During the early part of the Revolution, he left the army to fight for Corsican independence, but fell out with the leaders of that movement and ended up supporting France.

When the city of Toulon declared for the monarchy and invited the British in, Napoleon reported for duty to command parts of the artillery. His actions proved vital to the success of the siege, when he sited and maintained an exposed battery of guns that cracked the fortress’ walls. He was promoted to command the artillery of the Army of Italy, where he effectively made himself the chief of staff and plans for the army. He planned the offensive of 1794, which gained control of several passes into the Kingdom of Piedmont. After these attacks, the Austrians counterattacked, but the Armies of Italy and the Alps drove back this attack

In 1795, Napoleon was relieved from the Army of Italy, and entered a state of limbo. He was supposed to go to fight against rebels in the Vendee, but tried to get out of it in order to join the French mission to the Ottoman Empire, where he hoped to get hired on as a mercenary in service to the Sultan. During this wriggling, he was effectively fired for disloyalty. However, fate intervened. While he languished without a job, political turmoil overcame the Committee for Public Safety. After Robespierre’s death left a vacuum at the top, a number of factions vied to take command. In October of 1795, a crowd of Royalists rose to overthrow the Committee once and for all, and restore the Bourbons. Paul Barras asked Napoleon to lead the defense of the Committee, which Napoleon accepted. He then grabbed all the cannon he could, and cleared away the Royalists with a close range cannonade. Barras and his supporters formed a new government, the Directory- effectively, a junta that ran the French Republic- and then rewarded Napoleon’s loyalty with a new command, the Army of Italy.

For the French military, 1795 was a year of stalemate. On the Rhine frontier, the armies of the Sambre et Meuse, under Pichegru, and the Moselle, under Jourdan, launched a two prong offensive into Germany. However, the Austrians paid off Pichegru, so that he stood idle long enough for the Austrians to overwhelm Jourdan at the Battle of Hoscht, and the French retreated back to the Rhine. The war on the Rhine sucked in French reinforcements, depleting the Army of Italy. The Austrians launched a major counterattack, driving the French from Piedmont and Genoa, and retaking the passes.

The Italian Campaign to the Siege of Mantua

Napoleon’s swift actions to save the Directory made him something of a celebrity in Paris and around France. He became fairly popular, and even married Paul Barras’ former girlfriend, Josephine. A popular general with nothing to do hanging around the capital of a barely functioning government is never welcome. Napoleon’s station demanded an army command, so the Directory sent him to command the worst army in the French Empire, the Army of Italy, and then game him an impossible job: The conquest and looting of northern Italy. (The Directory really needed cash, both for the government and their escape-to-London-and-live-like-kings fund.) Napoleon could expect some support from the Army of the Alps, which was small.

Meanwhile, the Directory planned for the main offensive to come across the Rhine. Two large armies, the Moselle and Sambre et Meuse, under the commands of Moreau and Jourdan, respectively, received reinforcement over the winter. Jourdan we know, but Moreau had led several strong campaigns in Germany in 1793 and 1794, and, effectively, the two were the varsity, as far as the French were concerned. Against them, the Austrians deployed two armies, under Archduke Charles- far and away their best general of the era- and Wurmser. All of these armies were about 70,000 men each. Another 15,000 or so men guarded the coasts of France. Napoleon commanded about 65,000 men, and faced the Austrian Beauleiu, with about the same numbers.

Strategic Situation

Napoleon took command in late March, and immediately began moving to attack- in general, his energy and speed, compared to the activity level of the Austrians, was a major factor in his success. By acting quickly, he hoped to cross the Alps, and seize control of Piedmont before the Austrian army could arrive to reinforce the Peidmontese and control the passes in Italy. Napoleon needed to seize control of the passes into Italy, and launched a series of attacks against the gap between the Piedmontese and Austrian armies, seizing control of a strategic pass, then exploiting his successes to move into terrain more suited to maneuver. He then turned west, falling on the Piedmontese and destroying their army in a series of actions throughout April.

Opening Moves

Destruction of the Piedmontese

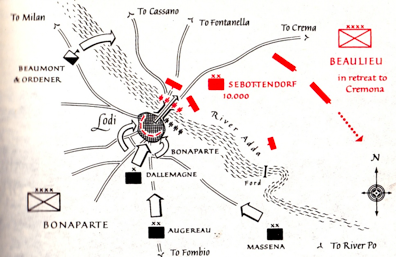

With the Piedmontese out of the fight, the French were across the Alps, were out of a numbers disadvantage, and had their western flank secure. Napoleon requested more troops from Kellerman’s Army of the Alps, and turned east to face the Austrians, racing to the scene of the action. The two armies met near the Po River. The French sent elements downriver to cross, turning the flank of the Austrian position. Beaulieu, the Austrian commander, began retreating back to the Quadrilateral fortresses around Mantua, where Austrian strength and supply in Italy was concentrated. Beaulieu stopped his retreat at the Adda, where he held a bridge outside the town of Lodi.

Beaulieu left the bridge under the cover his rearguard, who blocked the bridge with two lines of infantry and cannons. Over the course of the day, Napoleon’s army came forward, and Napoleon brought up cannon to bombard across the river. At the same time, he sent his cavalry upriver to a ford, so that they could cross and force the Austrian flank. The cannonade softened up Austrian lines in preparation for a storming of the bridge, timed with the flank attack by the cavalry, forcing an Austrian retreat. Beaulieu retreated to the Minco River, then back to the fortress of Mantua. The siege of Mantua would become the focus of the rest of the Italian campaign.

Battle of Lodi

Napoleon’s Advance to Mantua

The Battle of Castiglione

The Austrians realized that something was up in Italy as Napoleon closed on Mantua, and decided it was time to stop dicking around. They pulled Wurmser off the Rhine, and sent him, with some reinforcements, to relieve Beaulieu. Wurmser decided it was time for the Empire to strike back, and he took the offensive out of his base at Trento, with the intention of relieving the Mantua garrison and driving Napoleon back across the Po River. Wurmser sent his men in three columns down into Italy, with the intent of meeting Napoleon’s besieging army ourside of Mantua.

Meanwhile, Napoleon scrambled to put together a proper siege train, and invested Mantua formally on July 4th, 1796. He stationed his men on the approaches to Mantua, but they were unable to stop Wurmser’s attack. Wumser’s western column drove to the city of Bresica, seizing control of the town and capturing it’s garrison, while his central column blasted Massena, one of Napoleon’s subordinates, right out of the passes, driving past them. Napoleon had no choice but to abandon the siege itself, and reconcentrate his forces. However, he was able to put his army together faster than Wurmser could, and this allowed him to fall on the westernmost Austrian column with his full force. After a series of maneuvers against it in late July, this column retreated back into the Alps.

Meanwhile, Wurmser marched to Mantua. He destroyed the French siegeworks, captured Napoleon’s siege artillery, reinforced the garrison in the fortress, loaded the place up with food, and evacuated all the Austrian sick and wounded from the fortress. He then turned against Napoleon, marching his way to meet the French on the route back to Mantua, outside the town of Castiglione

Wurmser Strikes Back

On August 2nd, the Austrian advanced guard found Napoleon, and Wurmser ordered his western column to get its act together and fall on the French rear. Napoleon managed to delay this column over the course of the 3rd and 4th, while both he and Wursmer reassembled their armies from the countryside outside Castiglione. In the end, Napoleon assembled 30,000 men against Wurmser’s 25,000. Wurmser held the road to Mantua, so Napoleon needed to attack to force the way open to reopen the siege of the city.

Wurmser drew his forces up in a fairly traditional order: two lines of infantry, anchored between the city of Solferino on his right, and the fortified hill of Monte Medolano on his left. Light cavalry held his flanks, with a strong infantry and cavalry reserve. Napoleon drew up across from Wurmser, with his men in columns of attack, with skirmishers to the front. He also had few thousand men coming to him from Mantua, and he organized them to attack the Austrian left-rear flank. The battle opened with a French attack against the center and right flank. The French intended for this attack to pin the Austrian center, while the flank attack developed. Wurmser responded to this flank attack by pulling men from his reserve and second line to refuse his left flank, anchoring them against Monte Medolano, turning it into the hinge of his position.

The Battle

Napoleon decided that the best place to try and break the Austrian position was Medolano- if he could attack there, he would rupture Wurmser’s front, without any Austrian reserve to stop his attacks. To assist this effort, he ordered his center to retreat, pulling the Austrians forward and lengthening their overall lines, making reinforcement of Medolano more difficult. As he did this, more French came to attack the Austrian rear, pulling Wurmser’s forces apart further. At this point, Napoleon launched his assault of Monte Medolano. His artillery commander brought up artillery to point blank range to support a column as it fell on the fortifications at the top of the hill. The attack proved a success after much hard fighting. Napoleon followed this up with attacks across the center and right, threatening to envelop Wurmser.

With the French breaking through his lines, Wurmser began to organize his retreat off the field to the north. He reorganized his lines quickly and began pulling himself up to the north. His last reserves, his heavy cavalry, attacked the French, forcing them to stop their attacks long enough for him to get his army out intact. He moved back to the north, towards Trento and resupply and reinforcement.

In the end, the battle cost the Austrians about 700 dead and 1500 wounded, with another 1000 captured. The French lost about 500 dead and 1000 wounded in the fighting, and held the field at the end of the battle. Napoleon returned to Mantua, but no longer had the artillery he needed to press the siege. He was forced to blockade the fortress, trapping the garrison in the city while Wurmser readied his army for another relief effort.

Meanwhile, up in the north, things went poorly for the French. Across the spring and summer, Archduke Charles, who took overall command of the Austrians after Wurmser left, played a skillful game of concentrating against one French army, then the other, checking one advance before driving his army to stop the other army. Neither Moreau or Jourdan could force Charles into battle in a disadvantageous position, and Charles won a string of victories. He defeated Jourdan at Amberg and Wurzberg, driving him back across the Rhine before turning again to Moreau, defeating him at Emmindengin. Charles used the same sort of operational methods as Napoleon, moving and concentrating his men quickly before the French could, and used a combination of French style column attacks and traditional linear defenses in order to carry the day.

If France was going to succeed in 1796, it would have to come from Napoleon following up his victory at Castiglione.

If you like this post, and would like to read more, feel free to look into the archive.