Three-star in-state linebacker CJ Sanna commits to Ohio State.

Well, that was a hell of a game over Bye Week. Go Bucks!

But, in all seriousness, I think we saw that there will be a lot of jobs open at some big name schools come the off season. If you ever wanted to live in LA or Baton Rouge, I think it’s time to get your resume ready.

This week we’ll wrap up the 37th Infantry’s World War II history, with the last major battle they fought on Luzon in 1945. After the Battle of Baguio, the 37th would spend the rest of the war mopping up Japanese resistance on the island, a process that was almost complete by the time Japan finally surrendered.

The Luzon Situation

While Manila was an important objective for the United States, its defense wasn’t really part of the Japanese plans. The bulk of Japanese forces on the island had retreated to the hilly jungles that occupy much of the inland parts of the island, and planned to make their stands there. The US needed to take Manila for a variety of reasons- the large numbers of prisoners there, the ability to use Manila’s ports as a supply point, and propagandistic reasons, both in the US and in the Islands themselves.

This advance split the Japanese on Luzon into, effectively, three groups. The Kembu Group, commanded by Sukada, occupied the part of Luzon west of the American advance, including Bataan and Corregidor. The Shinbu Force, under Yokoyama, controlled Luzon’s long eastern “tail,” while the bulk of northern Luzon fell under command of Yamashita himself. The sweep down to Manila, and the landings to the south of the city, split these forces apart while the US marched on the city.

While the 37th Infantry was either taking Manila, or reconstituting after the battle, follow-on US forces continued the attacks on Japanese forces on the island. Against the Kembu Group, US forces behind the 1st Cav and 37th turned west, and began pushing the Japanese against the sea from the east. On February 15th, other forces landed on Corregidor and the southern tip of Baatan, and began driving north. By the 20th, the area under Kembu’s control was largely clear.

Fighting against Shinbu took longer, since the area was narrower, more conducive to defense, and there were just more Japanese. In February, American attacks split the Shinbu group in two, separating the tail of the island from the fortified highlands east of Manila. These early attacks came in February, but the fighting would last quite some time. It wouldn’t be until the end of May, after the Battle of Baguio, that the fortified highlands fell. However, landings in early April at the extreme eastern end of the island helped secure the area by the end of the month.

Fighting against Yamashita’s force would prove tricker. Not only was the terrain some of the toughest on the island, Japanese forces were commanded and led by one of the better Japanese commanders of the war. As a result, the Americans rather underestimated the forces needed to drive on the area, and the advance was slow going through February and March. In the eastern part of the island, US forces had pushed as far as Balen Bay, while along the eastern coast, US forces had made it to San Fernando. However, the main push would have to wait until other forces could come up and support further attacks into the Japanese defensive zone.

Ultimately, one of those divisions would be the 37th, which returned to the line in April, 1945

The Battle of Baguio

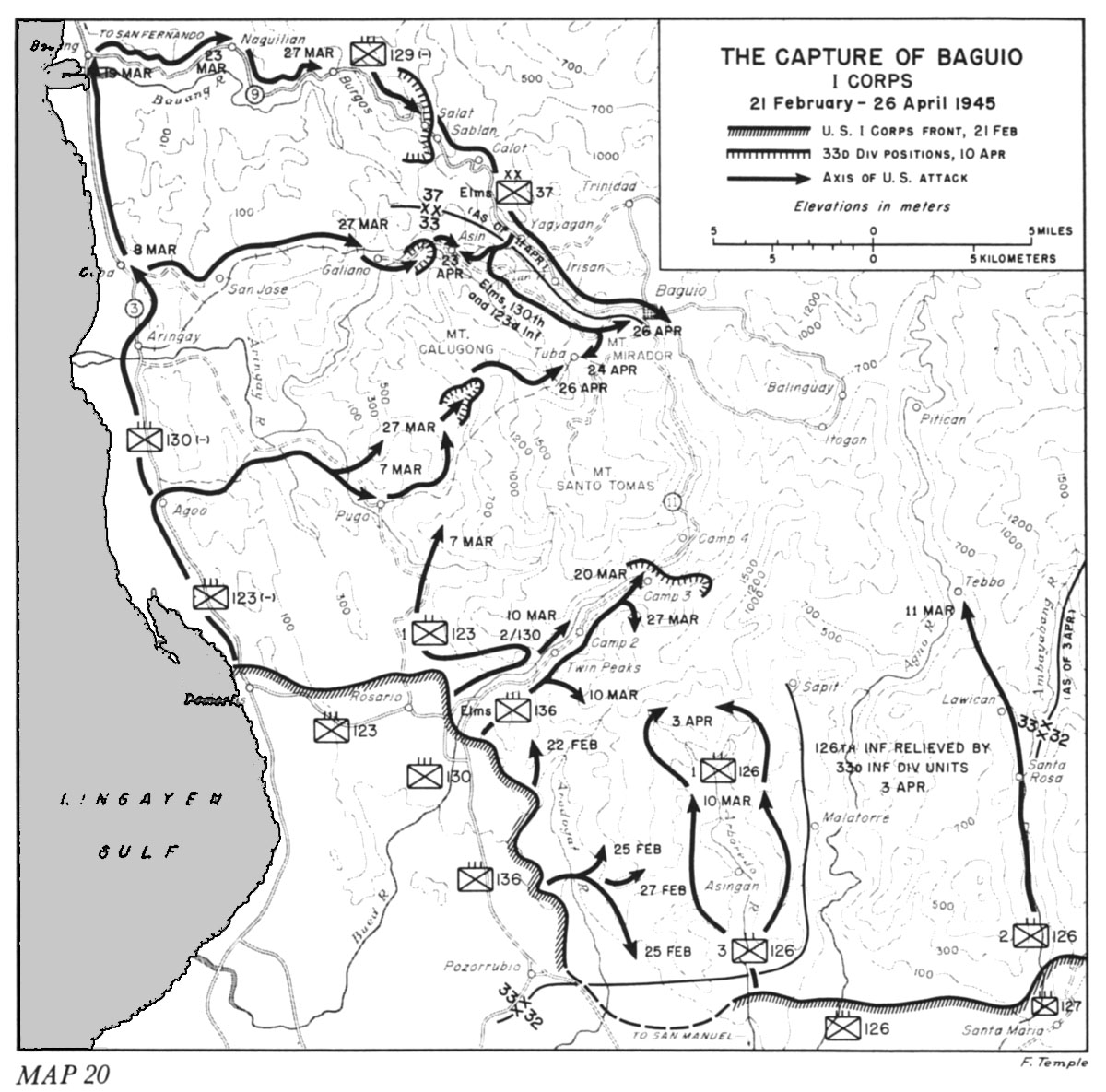

During the Battle of Manila and shortly afterwards, 33rd Infantry held the task of moving on Baguio, an important regional administrative center and headquarters for local Japanese defensive efforts. These attacks were slow for a variety of reasons. 33rd Division didn’t have the manpower for a full on drive in the area, and the terrain didn’t help much. Throughout March, the 33rd Division moved up three major routes of advance, up to river valleys to the south, and Route 11 to the west. However, the Japanese had these routes well scouted, and held the ridges and hills above these routes. Clearing them was a slow process, as the Japanese delayed and gave ground skillfully to keep American casualties high and the rate of advance slow. Terrain also kept these routes of advance separate, meaning the forces moving on each route weren’t mutually supporting, and the attacks were, operationally, frontal attacks up the routes.

In order to speed up the attack on Baguio, the Americans needed more forces. Some help came from Filipino guerillas acting in the north, particularly the 66th Provisional Regiment. These troops applied pressure, and forced the Japanese to disperse some of their reserves to deal with them. But, there just weren’t enough of them, and they weren’t well equipped enough, to force the Japanese to pull large numbers of men off the 33rd Division’s front to allow for a more rapid advance. However, these attacks, both from the 33rd and 66th, had spread Japanese forces in the area pretty thinly.

By the end of March, the 37th had recovered well enough to redeploy to the front. In order to get this particular area moving forward, I Corps decided to send the 37th to support the 33rd. However, unlike the attacks made by the 33rd, the 37th would stay concentrated and move down another axis of advance, Route 9 from San Fernando to Baguio. While Route 9 wasn’t exactly a walk in the park- in fact, it was both sufficiently rugged and far from American supply routes that the 33rd rejected it as a route of attack- the 37th had the manpower and supply sources by April 7st that it could work down this Route, hit the main Japanese line on the flanks, and open up the road to Baguio. This would take advantage of the work done by the 33rd in March, and also put the main effort on, realtively, speaking, fresh troops.

On April 11th, the 37th opened its attack against the Japanese forces in front of them at the town of Salbang. These forces, mostly consisting of the 56th Japanese Infantry Brigade, didn’t have the forces to stop an American division, particularly one with heavy supporting artillery and tanks. This firepower blew a hole open in Japanese defenses during the 12-15th, and allowed the Americans to open Route 9. The veterans of the 37th kept moving hard and fast against the Japanese, who, because of the previous month’s fighting, had been weakened in terms of manpower, food and supplies. These attacks also supported some elements of the 33rd, and allowed for movement along the northwestern part of the battle area.

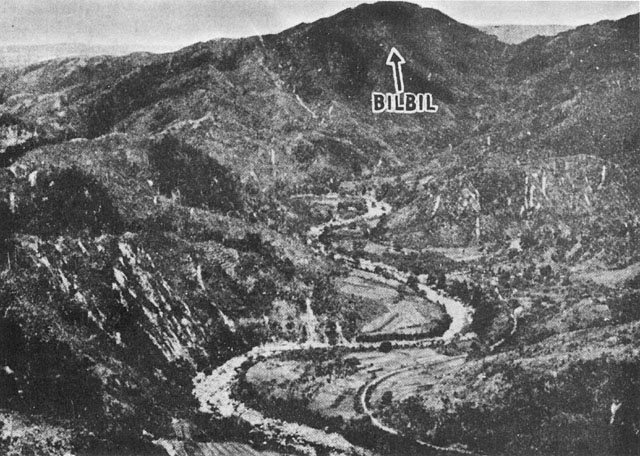

In an effort to slow down the American advance to give his command time to redeploy, General Saito, the local Japanese commander, sent what reserves he had to the bridge over the Irisan Gorge. The Irisan Gorge cut its way through a series of hills and ridges, and, in better days, as bridge carried Route 9’s traffic over it. The route ran along what little low, flat ground there was in the area, and was surrounded by sharp, steep hills along both sides of the ridge. It was a good place to make a stand.

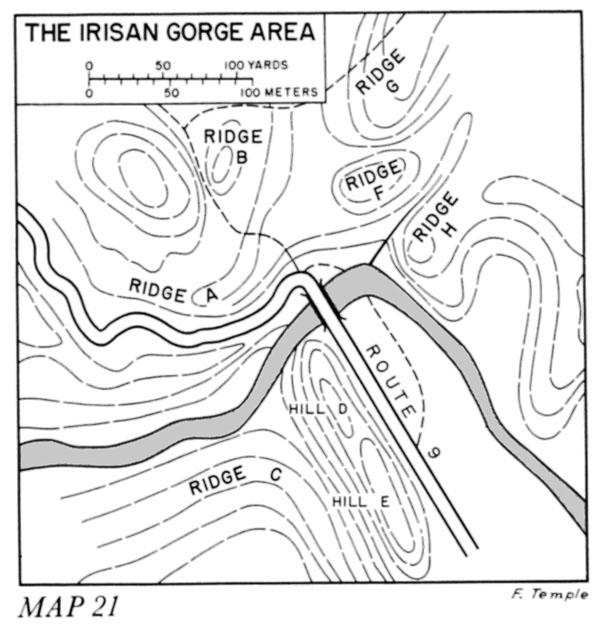

The Japanese took up their main positions on Ridges A and B, with additional forces on F and H to control the area where Route 9 made a turn onto the bridges. Further forces went to Ridge G, to secure communications, and D and E were to backstop the others, since the Japanese considered Hill C too rugged to effectively cross. While not heavily fortified, the Japanese did dig in and sight their main weapons well, and could use some caves in the area for their anti-tank guns.

On the morning of the 17th, the lead elements of the 37th tried to force the road directly, using tanks and close range howitzer fire to try and drive the Japanese off of Ridges F and H to take the bridge. These attacks failed, and the Americans fell back behind Ridge A. That afternoon, the Americans settled into a more methodical approach. Rather than try to take control of the area by a Coup de Main again, they settled for an enveloping attack on Ridge A, attacking from the north, west, and south. By the end of the day, the Japanese had been pushed off Ridge A, giving the Americans a jumping off point for moving against the other positions.

For the 18th, the Americans planned two attacks- one from Ridge A over to Ridge B, then sweeping over G, F and H. Another force crossed the Irisan river to the west, and would attack up C, and then hit D and E, giving the Americans control of both sides of the bridge, clearing out Japanese resistance, and opening the road. Like most plans, this one did not work out quite as well as hoped. Japanese forces on Ridge F could fire upon the Americans trying to attack the flank of Ridge B, which forced the Americans to attempt several frontal assaults on B all through the 18th. These attacks largely failed, leaving the Americans with just a foothold ad the base of the hill. However, to the south, the attack went much more swimmingly. Supported by heavy guns, the Americans cleated the skirmish line on Hill C, and prepared for an attack on D and E on the 19th.

The 19th saw more American success. Given how tough the Irisan nut was proving, more firepower came into the area. A massive airstrike on Hill F knocked out most of the Japanese defenders, and heavy artillery pounded the Japanese on Ridge B for most of the day. Still the attack on B was quite slow going until a machine gun platoon worked its way around the Japanese flank, and gained a position where it could fire down the main line of Japanese resistance in the afternoon. This broke the Japanese defense, and what remained retreated towards G and H. On the other side of the river, the Japanese expected an attack from the north, and got one from the south. With heavy supporting fire from units on Hill C, the American attacking forces swept over the ridgeline. Those Japanese still alive bolted down the road foe Baguio. With B and D-E under American control, the Japanese that remained were isolated, and could expect no resupply or reinforcement.

On the 20th, the Americans swept up ridge F, but ran into trouble against the forces on Ridge G. The first attack, a frontal assault in the morning, failed. However, in the afternoon, the troops on Ridge F swung against the Japanese flank, and by the end of the day, the Japanese only held H. Heavy air and artillery attacks on the 21st broke the main Japanese positon, and American troops overran it on the afternoon of the 21st. The fighting had left, in the end, 40 dead Americans, with 160 wounded, and 500 dead Japanese.

The collapse of the Irisan Gorge defense threw Japanese plans into disarray. Saito had hoped to make the area the anchor of a new main line of resistance near Baguio, but the rapidity of the 37th’s advance and attacks at Irisan made that impossible. The 33rd continued advancing from the south as well, pinning Saito into a box. In order to prevent the total envelopment of his forces, he left the area, leaving behind minimal forces to cover his retreat back towards Yamashita’s main area of resistance. Men from the 37th stopped after the Irisan Gorge to wait for support from the 33rd, then entered the city itself on the 26 and 27th. After brief fighting, US troops took the city. The 33rd would take up the pursuit of Saito, with the 37th would fall into the reserves until later in May, when it would help clear the Cayugan Valley of Japanese guerillas until August 15th, when Japanese forces in the area surrendered.

Here’s some footage of the entry into Baguio:

Final Notes

The Battle for Luzon was the largest ground campaign of the Pacific War. 280,000 Americans clashed with 275,000 Japanese for control of one of the largest islands in the Pacific. Control of Luzon also allowed movement against other strategic targets in the area, such as the Japanese bases on Formosa, and the oil fields of Borneo, which came under attack in the summer of 1945, using Philippine bases. Other attacks during that summer included attacks on the central islands in the Philippines, and, in the central Pacific, attacks against Iwo Jima and Okinawa. In the end, fighting on Luzon claimed 10,500 American lives, and wounded another 36,000. 205,000 Japanese died on the island, with 70,000 or so surrendering after the war.

While Luzon would be the last campaign for the 37th, that was largely a result of the atomic bombs. The 37th, after refitting and replacements, was slated for Operations Coronet, the second invasion as part of Downfall, the attack on the Japanese home islands. The 37th would have been part of the attack against Yokosuka, up the Kanto plan, an into Toyko itself. Frankly, I can’t imagine that would have been an easy task, and I don’t expect the Japanese would have made it easy to take their capital- it would have been Manila, over and over and over again for months, most likely. Fortunately, that never came to pass.

The war itself cost the 37th Infantry 5,960 casualties. Of these, 1348 men died, while 1386 men were wounded badly enough to need evacuation to the United States. 3225 men were wounded, but able to return to service in the theatre in some capacity.

The 37th also earned it share of medals, including 7 Medals of Honor. I’ve put the citations together in a separate post, which you can get by clicking here.

As usual, if you enjoyed this and want to discuss it further, feel free to reply below. There’s also the archive, which you can access by clicking here, if you want to look more into military history here at 11W.

See you next week, for something completely different.

This seems like appropriate music for the end of this part of the series: