Hawai’i is roughly 4,500 miles southwest of Columbus.

To get there in 2021 requires 10-12 hours of travel time, depending on how many layovers you end up having. When I visited about 10 years ago, I distinctly remember the bulk of the flight being over the bluest expanse of water that you'll ever see. It simultaneously makes you appreciate this beautiful world we live in and also emphasizes that you're traveling to one of the most remote inhabited places on the planet in a metal tube traveling at hundreds of miles per hour, tens of thousands of feet in the air.

So, having landed at Daniel K. Inouye International Airport in Honolulu, you aren't really sure what to expect. You, a mainlander, have a preconceived image of a place that you've cultivated from Forgetting Sarah Marshall or Hawaii Five-0 that may or may not reflect reality, and you're excited to see if what you find matches the image in your head. And if you're from Ohio or the Midwest, the spatial whiplash can be especially jarring because the two places might as well exist on different planes of reality.

But first I just needed to find a bathroom, and in the process of meandering down a long corridor and gawking at the scenery outside, I stumbled on a temporary Hawai'i Sports Hall of Fame installation.

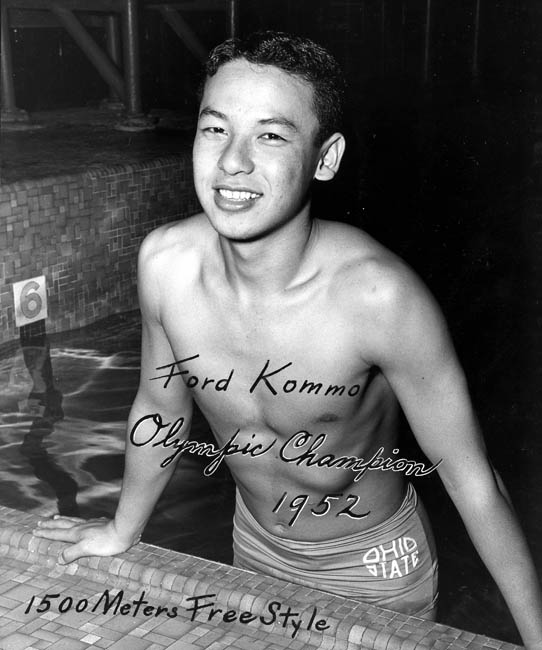

Plaques with names like Ford Hiroshi Konno, Yoshi Oyakawa, and Keo Nakama jumped out at me, not just because they were swimmers (a sport I love), but because in their biographies they all had something in common that I didn't expect: they weren't just Olympians, they were Ohio State Buckeyes.

Earlier this week, Hunter Armstrong became the first Ohio State swimmer to qualify for the U.S. Olympic Team since 1956 by finishing second to reigning Olympic champion Ryan Murphy by a fraction of a second in the 100-meter backstroke. That information comes with the caveat that his inclusion isn't yet official, as the final Olympic roster won't be announced until later today, but yeah, he's in:

“We are all just incredibly proud and happy for Hunter,” Bill Dorenkott, Ohio State director of swimming and diving said. “Hunter is a proud Ohioan who has just continued to get better and better. Ohio State has a rich history of U.S. Olympians and medal winners, but it’s been a while since we had one so this is a wonderful moment for Hunter, his hometown of Dover and for the Ohio State program.”

Armstrong, who started his collegiate swimming career at West Virginia before transferring to Ohio State, swam the best time of his life, completing the event in 52.67 seconds and coming all the way back from seventh at the mid-way mark in the race.

#TokyoOlympics

— Ohio State Buckeyes (@OhioStAthletics) June 16, 2021

@OhioStSwimDive Hunter Armstrong rallies to take 2nd in 100m backstroke at #OlympicTrials #GoBuckeyes Toky-OH!

pic.twitter.com/pCyKOEFaT7

A quick sidenote about the backstroke: it kicks ass. All of the four major strokes (freestyle, butterfly, breaststroke, back) in competitive swimming demand a certain approach and mentality, but backstroke requires a person willing to throw away everything sensical they've learned and then learn something new, and upside down.

Also you can't see anything and are kind of just praying you're swimming in a straight line. And also you're never completely sure where the edge of the pool is, so you're going to hit your head, a lot. And also you're just going to have to work around the fact that water is constantly in your face while you're trying to breathe. You aren't going to look cool, but on the other hand you don't have to deal with butterfly's turbo BS or whatever dark arts are involved with breaststroke.

Which is why backstroke rules.

And America rules in backstroke. Since 1996, the United States has won gold in every Olympics in both the men's 100-meter and 200-meter backstroke, going 12 for 12. The women haven't been quite as dominant, but going 6-for-12 in that same timespan in those same events is pretty incredible as well.

Hunter Armstrong will join Murphy in the 100 meters in Tokyo to attempt to continue that dominance, and in doing so will bring full circle a journey that started almost 100 years ago.

In Hawai’i I was fortunate enough to be able to meet Richard "Sonny" Tanabe, a legend in the swimming and freediving community who swam for the Hoosiers and represented the U.S. in the Olympics himself, and he explained to me how I ended up seeing so many Buckeyes represented so prominently in a place halfway around the world.

This is a story that has been better told and in more detail before, but it begins in the 1930s, in irrigation ditches surrounding the fields in rural Hawai’i where many locals first learned to swim. Coach Soichi Sakamoto started a club with the goal of getting kids to the Olympics, and his athletes almost immediately turned the heads of coaches like Ohio State's Mike Peppe. Peppe, who started Ohio State's swimming team, brought in Hawai'ian swimmers like future gold medalists Yoshi Oyakawa, Bill Smith, Ford Hiroshi Konno, and legendary swimmer Keo Nakama.

Nakama’s 3 varsity seasons at the Ohio State University were Big Ten and NCAA Championship years for Hall of Fame Coach Mike Peppe’s Buckeyes with Keo the captain his last two years. He also captained the University’s baseball team.

Nakama recalled that he was the victim of racism only once when he was on the mainland during World War II. And that his coach, Mike Peppe, punched out the Army colonel who thought it wrong that a guy who looked like the enemy was the Buckeyes’ star swimmer.

This influx of talent culminated in the United States’ domination of men's swimming in the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, where Buckeyes won five medals, three of them gold. The following 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne would be the last time that a Buckeye would represent the United States at that level, as the swimmers of Sakamoto and Peppe began to retire and make way for a new generation of athletes.

Hunter Armstrong will soon join that legacy, ending a 65-year drought for Buckeyes on the U.S. Olympic swimming team. And the best part? He'll be doing it in the 100-meter backstroke, the same event that Ohio State Buckeye Yoshi Oyakawa won gold in almost 70 years ago.