As we hit the longest part of the offseason (only 123 more days until Kickoff!), Film Study will begin to look at what’s happening in the college football world outside of Columbus. We’ll begin by taking a look at some of the schemes that the Buckeyes will face this fall that may be unfamiliar. Our first stop is in Annapolis, MD at the U.S. Naval Academy, focusing on the flexbone offense that has become a trademark for the Midshipmen.

Coming off a winless campaign in 2001, the Naval Academy turned the reigns over to Paul Johnson, then the Head Coach at Georgia Southern. Having won two Division 1-AA National Championships in 5 seasons, Johnson’s Flexbone offense had proven nearly unstoppable. Without traditional scholarships and difficult recruiting circumstances, Navy had been an option team for years by that point (Johnson was actually the Offensive Coordinator there in 1995-96), but had trouble consistently winning with the formula in place.

Within 2 years, Johnson and the Midshipmen went 10-2 and beat New Mexico in the Emerald Bowl, cracking the final AP top 25 for the first time in 41 years. The winning hasn’t stopped since then, even as Johnson left for Georgia Tech in 2008.

Since then, Johnson's former pupil Ken Niumatalolo has had only had one losing season, going 5-7 in in 2011. Niumatalolo has not changed much about the flexbone system Johnson set up, and the Georgia Tech offense gives us nearly as much insight into the Navy schemes as film of the team itself.

All three service academies run versions of the flexbone, but for the sake of the upcoming matchup in Baltimore this August between Ohio State and Navy, we’ll focus on the Paul Johnson/Ken Niumatalolo version.

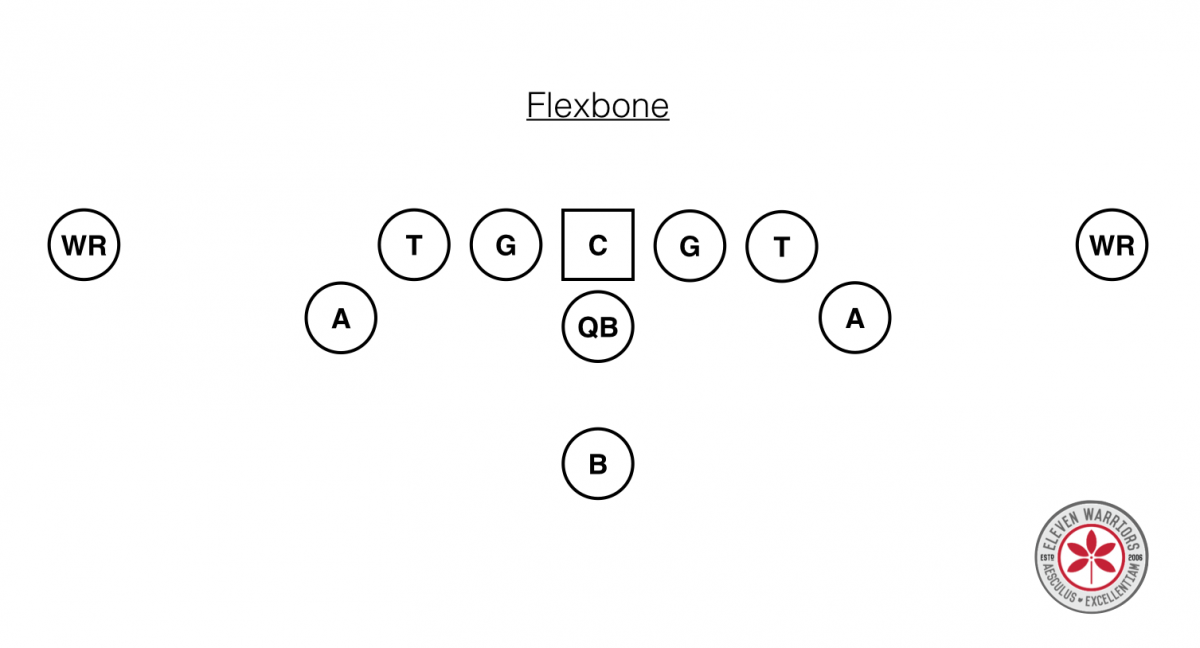

Base Offense

The engine of the Navy offense, as with any such modern scheme, is still the Quarterback. While the flexbone doesn’t require the same amount of decision-making in the passing game as a pro-style or spread offense, there are still plenty of decisions to be made, as Paul Johnson has noted in in the past.

Before the snap, he must identify all the defenders to read during a play, which can be up to three different players. Once the ball is snapped, he must be able to properly make multiple decisions to keep or give within only a fraction of a second, and then find the next man to read almost simultaneously. Finally, when they do throw the ball, often on play-action, he must be able to read a secondary like any other quarterback and find his open receiver.

Lining up directly behind the QB is the B back, which is often compared to an old-school, Larry Csonka-style Fullback who isn’t just there to block. This is not to say that a B back must be a bruiser that can only fall forward for 3 yards, as former Georgia Tech B back (and current Arizona Cardinals Running Back) Jonathan Dwyer showed. Dwyer was listed at 5’11” and 230lbs, with a build very similar to that of many “traditional” Tailbacks found across the NCAA and NFL. While the majority of the B’s runs are between the tackles, he will occasionally see the ball on the edge in the Speed Option, which we’ll get to shortly.

Finally, what separates the flexbone from nearly every other modern offense are the A backs. For anyone that ran the Wing-T offense in high school (a cousin of the flexbone), this position functions very similarly to the Wingback in that system. Often coming in motion behind the B back and acting as the tailback on triple options, the A back is often a quick open-field runner that shares a number of traits with the H position in Ohio State’s offense. However, the A must be able to run block, as they effectively replace a Tight End in the formation. Occasionally, the A will split out into the slot and create a three-receiver look, both to remove a defender from the box in running situations, as well as give the offense more opportunities to spread the defense horizontally in the passing game.

Triple Option

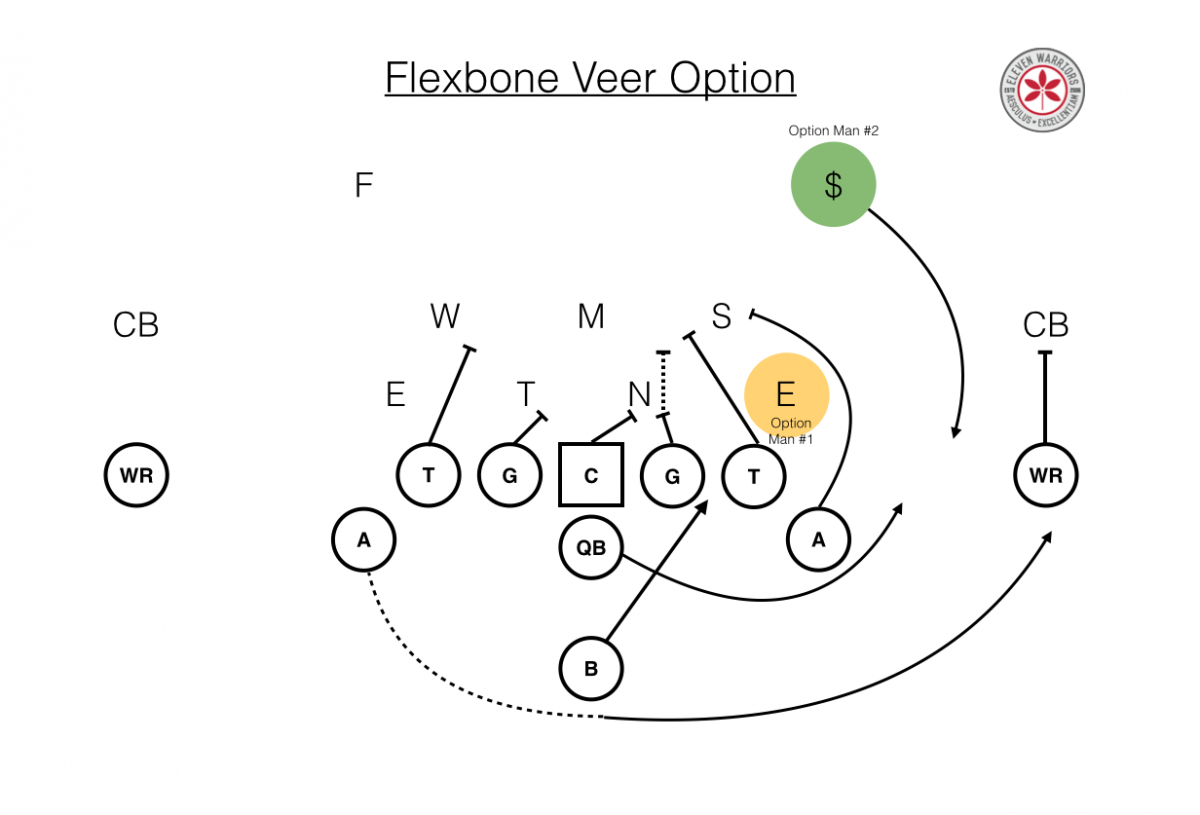

If one play defined the flexbone system, it would be the Triple “Veer” Option.

As seen in the diagram, the play is optioning two different edge defenders, often forcing a member of the secondary have to step up and make a tackle. The QB first reads the defensive linemen over the tackle (a DE in this diagram, but can be a DT depending on alignment), who is left unblocked. If he doesn’t step up and take away the B back dive, the QB will give the ball to the B back every time.

If the DE does attack the dive, then the QB will keep and go on to the second defender, which is usually an Outside Linebacker or Strong Safety. The QB will then read that defender as he turns the corner of the line, either pitching to the A back on the outside (that came in “rocket” motion before the snap), or keeping it himself if the defense over plays the pitch.

The key to consistently running the Veer is the B back, who must be featured in order to keep defenses from over-playing the outside pitch. Teams know the Veer is coming, but the offense must keep the defense from over-playing any specific option as the game goes on.

A common refrain we’ll hear from fans, opposing coaches, and pundits as the Navy game gets closer, is that defenses playing the triple option must play “assignment football.” There is some truth to that, being that each defender must know his responsibility on each play, knowing if and when he is supposed to take the B, the QB, or the A on a pitch.

However, what makes Navy so successful in this offense is their ability to deviate from their initial plan and make you wrong in your assignments. For instance, the Midshipmen will have the outside WR block the opposing CB in front of him, leaving the Free Safety as the player responsible for coming down and making a tackle on the pitch. Then, on the next play, the WR will block down on the Safety, not only blocking that player, but also bringing the CB that was assigned to cover him right along as well, effectively taking two players out of the play simultaneously.

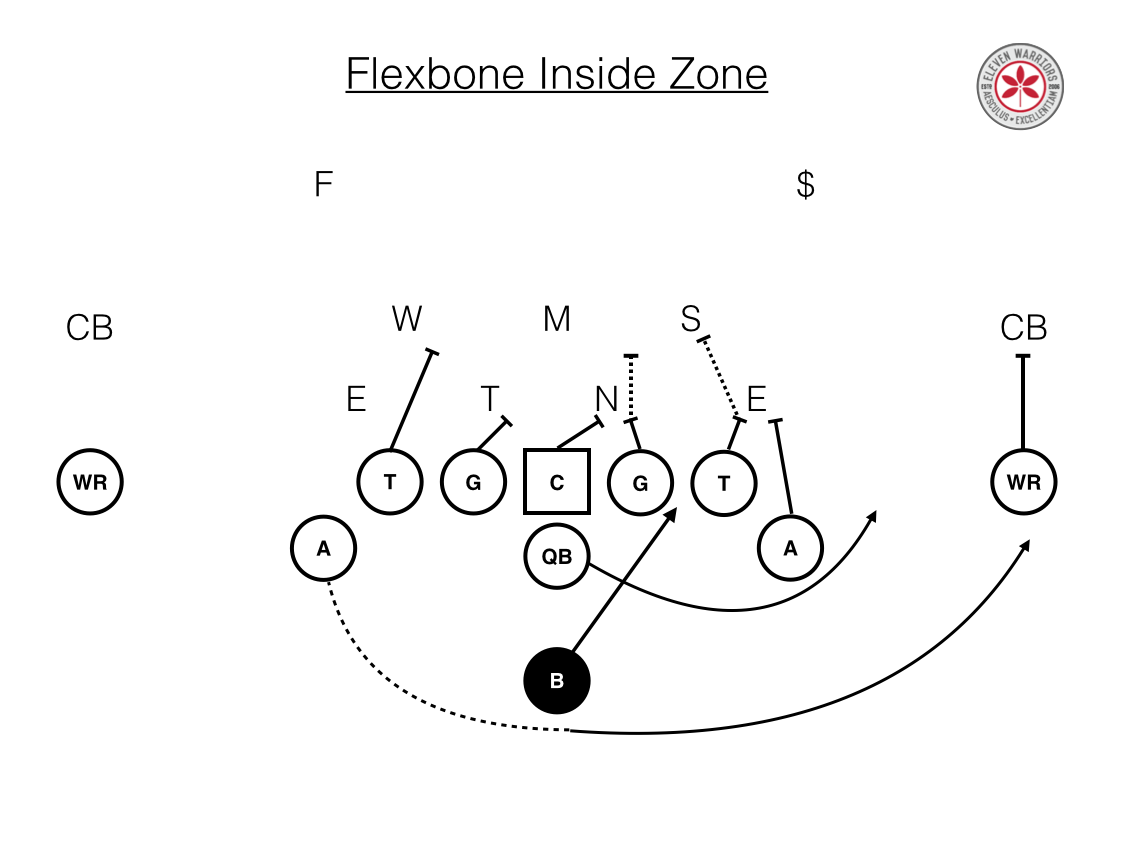

Inside Zone

For those of you that read 11W regularly, you’re probably able to draw the Inside Zone on the back on a napkin for any given stranger at this point, given its prominence within the Urban Meyer offensive system. While Navy runs this play from a different formation, the rules for the Offensive Line are basically the same as in any other scheme.

In order to keep defenses off balance, Navy will try to disguise Inside Zone as another Veer Option, by bringing the backside A back in motion and carrying out a fake with he and the QB. Instead of leaving the DE unblocked as the optioned defender though, he is now blocked and taken out of the play. Since Navy often can’t simply push their opponents around physically, they won’t rely too heavily on this play, but they will run it when a defense is consistently taking away the dive on the Veer option.

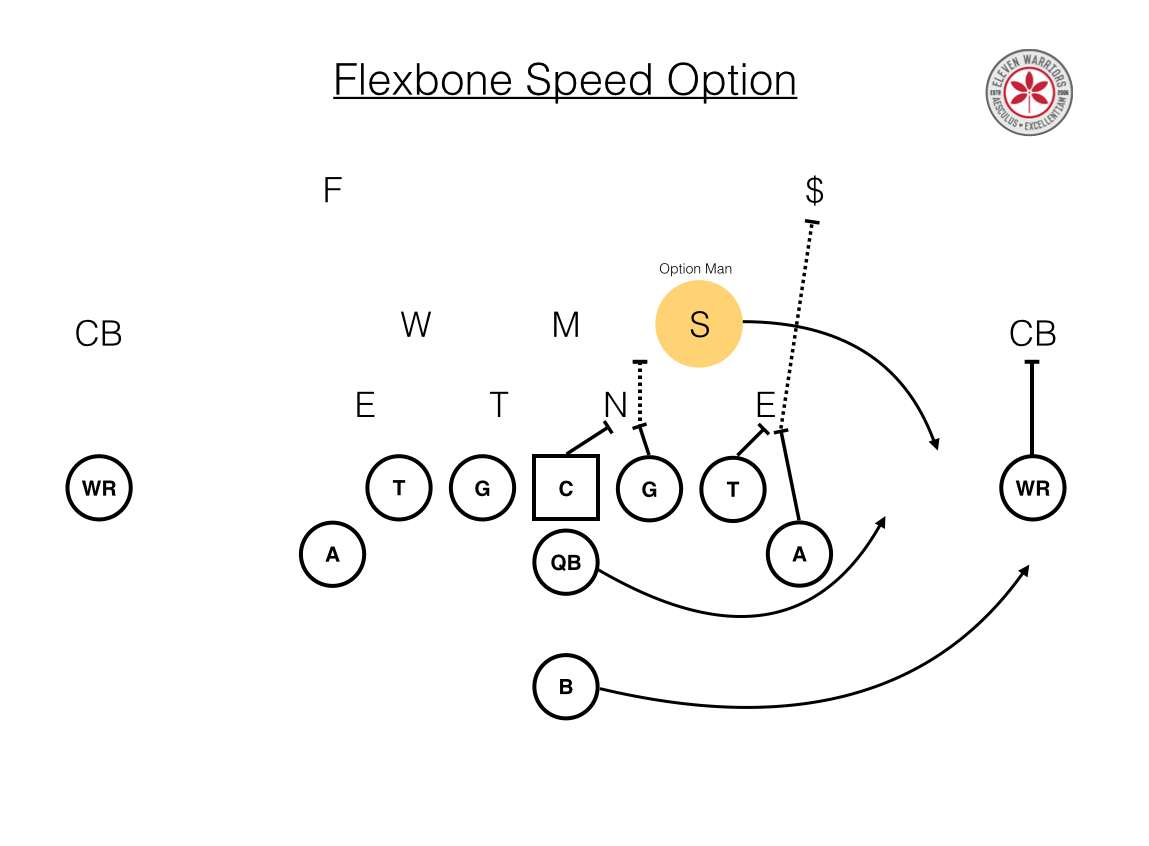

Speed Option

If the B back in the Navy offense is fast enough to cause problems on the edge, then we can expect to see a fair amount of the speed option in Baltimore. Without any motion from the A backs, the speed option is a basic one-read option run, aiming to get the ball to the edge thanks to a numerical advantage.

By leaving one of the outside defenders (can be a DE, OLB, or Safety) unblocked, the QB simply reads this option defender and decides whether to keep or pitch. Unlike the veer option, which takes some time to develop, the Speed Option gets the ball on the edge quickly, not leaving the backside defenders much time to get to the ball and help.

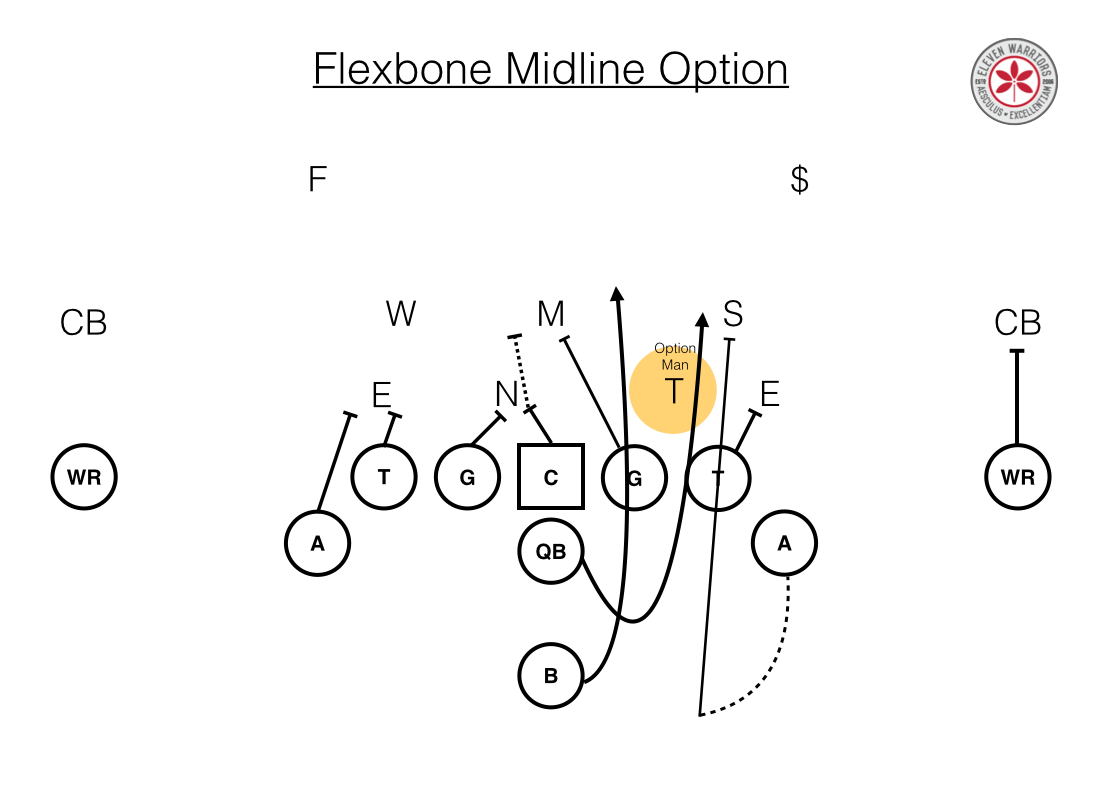

Midline Option

As Chip Kelly’s Oregon offense began taking the college football world by storm, football minds across the country noticed that his spread option offense not only called on his QB to read defensive ends, but also interior defensive linemen. Thus, many of us came to know the Midline option. This has been a staple of the Flexbone for years though.

As a wrinkle to the dive in the Veer option, Navy will leave the interior tackle unblocked, leaving him to attack the B as he runs inside. If the DT goes after the B (which is his responsibility), the QB will keep and follow a lead block inside.

The QB is given a lead block from an unlikely source though, as the A that goes in motion then cuts up through the hole and take out a linebacker or safety on the second level.

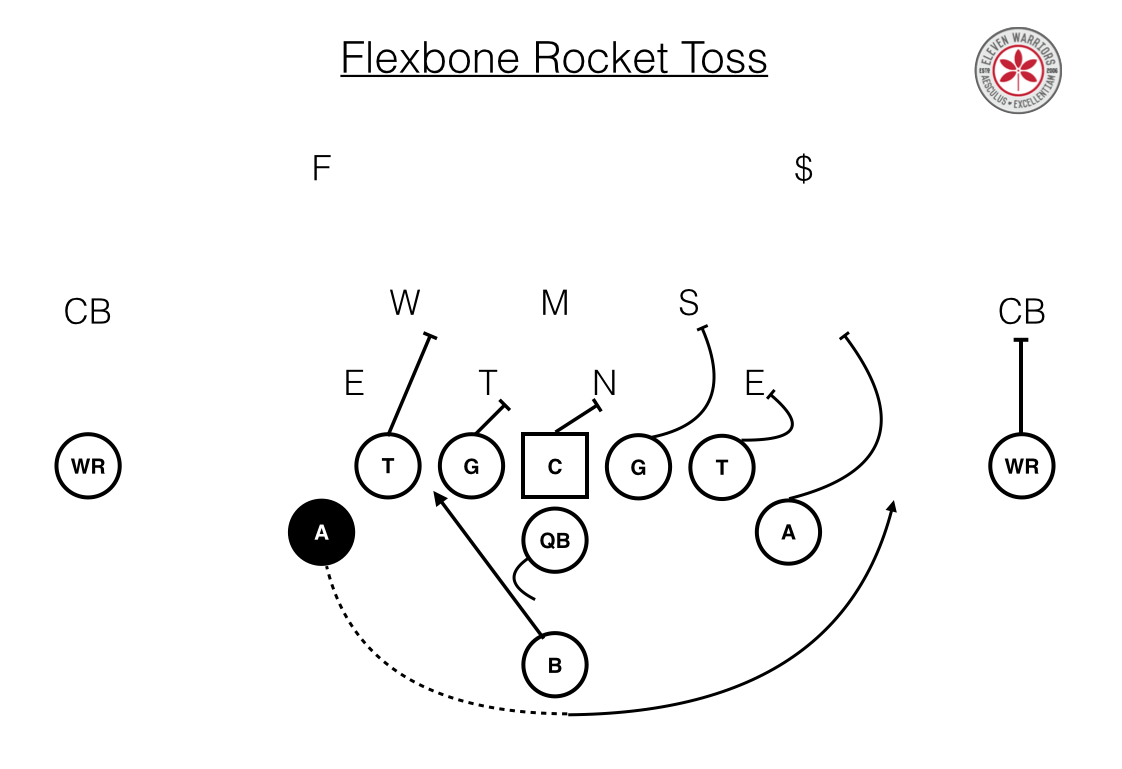

Rocket Toss

Once a defense has become flat-footed and waiting for the Veer, Midline, or Speed Options to develop, Navy will hit them with the Rocket Toss. Much like the Inside Zone is meant to quickly get the ball inside, the Rocket Toss is the quickest way to get the ball outside, along with a host of lead blockers.

Once again, the devil is in the details here, as the QB and B back will go away from the toss, pulling the linebackers that have been watching him on the dive all day long to hopefully take a false step away from the action.

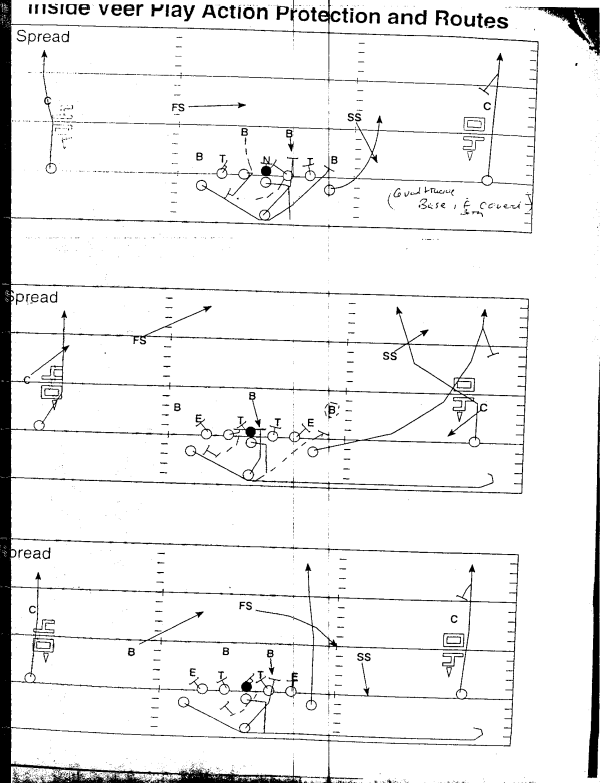

Play-Action Passes

Finally, once a defense has gotten so tired of getting beaten up by the run and have all 11 sets of eyes in the backfield, the Midshipmen will take their shot downfield. Navy has a number of passing concepts built off every kind of motion and fake imaginable, but the routes themselves are nearly all vertical. One of the more surprising pieces to the Paul Johnson/Navy puzzle is the effect the run and shoot offense has on their passing game.

Although they don’t do it often (passing attempts per game ranged from 4 to 18 last season), Navy will attack a defense with vertical threats. The quarter rolls from the QB off fakes, and rules that define the way a receiver runs his route, there are a number of concepts that may remind fans of the old Houston Oilers. The A backs simply become the slot receivers in this instance, occupying the opposing safeties and leaving the wide receivers in single coverage on the outside.

Conclusion

Needless to say, the Navy playbook includes more than 8 plays. There are countless counters, motions, formations, and rules for all 11 players, trying to catch the defense off guard. What has made the Navy (and now, Georgia Tech) offense so successful is not the ability to hit one play over and over, but to be able to recognize the counters a defense will make, and have an immediate answer to that counter. The Flexbone is not a simple offense by any means, and the minute details are what define success and failure for the teams which employ it.

Next week, we’ll take a look at some of the ways that Chris Ash, Luke Fickell, and the Ohio State defense will likely try to stop this system, which they rarely see.