Former Santa Clara standout Christoph Tilly, a top-10 center in the transfer portal, commits to Ohio State.

The 'Spread' is here to stay.

Though it took nearly 15 years to do so, spread offenses have become the norm at every level of football. Whether it's Tom Brady or a 12-year-old lining up at quarterback, there's a good chance he's doing so from a shotgun set with three or more receivers stretched from one sideline to the other.

Once conservative stalwarts like Alabama and Wisconsin finally embraced this wide-open version of offense around the mid-point of the 2010s, nearly every college program in the country (outside of the service academies) began to look more or less the same on that side of the ball.

Almost every team uses both zone and gap schemes to run the ball with some kind of option element to keep defenses honest. Elements of West Coast, Air Raid, and the Run-and-Shoot passing games can be found in most playbooks, meaning the most creative play-callers earn that title from the way they disguise existing concepts rather than drawing up new plays themselves.

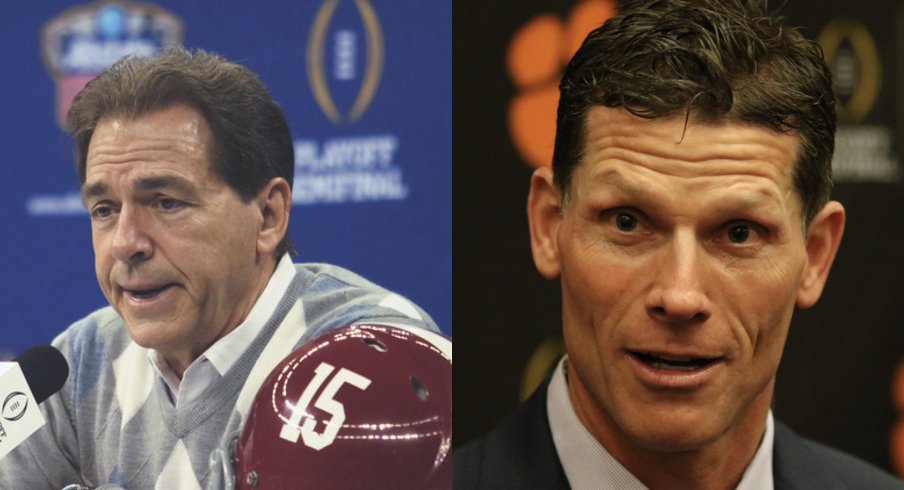

While young, offensive-minded coaches like Lincoln Riley, Ryan Day, and Joe Brady often draw the most media attention, it's the top defensive minds that often find themselves playing for championships year after year. With the exception of Ohio State's victory in the inaugural College Football Playoff, the trophy has been handed to a team with either the godfather of modern defense (Nick Saban) or one of the two highest-paid assistants in the entire sport - both of whom coached on that side of the ball. In fact, the six highest-paid assistant coaches last season were all defensive coordinators, showing the importance of slowing down opponents in a game that has grown more and more offensive-minded in the past decade.

Unlike their offensive counterparts, though, the top annual contenders for the CFP employ very different philosophies when it comes to stopping those spread offenses. Though the differences in alignment, personnel, and technique may be more difficult for the average viewer to spot, they have come to define the stylistic differences between programs far more so than when they have the ball.

Let's take a look:

Alabama & Georgia

Nick Saban may carry the most complex defense in football. Not SEC football or college football, but in the entire sport itself. His 2015 defensive playbook was 543 pages long, filled with virtually every formation and coverage, each with countless blitzes and adjustments that allow him to have the perfect call for anything an offense throws at him.

This versatility allows the Crimson Tide defense to play many different styles, though they most often play some version of a single-high defense on early downs to play the run. The most common (and famous) call from Saban in these situations is his three-deep match scheme known as Rip/Liz, in which the defense starts in a two-deep shell before rotating to a one-high look at the snap.

This rotation gives the defense an eighth defender in the box to defend against the run while playing a zone-match coverage behind it. In this type of coverage, defenders wait for the receivers to declare routes before picking them up in their assigned zones, but playing them with a technique that looks like man-coverage downfield.

This pattern-match technique was famously born out of necessity when Saban coached with Bill Bellichick in the early 90s and has become one of the most popular systems in the high school, college, and NFL ranks.

Former Alabama DC Kirby Smart took that massive playbook with him to Athens when he became Georgia's head coach in 2016, and today the two defenses remain quite similar. Though Smart and Saban have varying levels of aggression and lean on different schemes with their backs against the wall, the menus from which they can choose are nearly identical.

In passing situations, both teams rely more on two-deep match coverage, though this time it is based initially on man-coverage assignments than pre-ordained zones (known as man-match coverage). The system is deepest against 3x1 sets, as both Saban and Smart have myriad ways of handling such looks.

Stubbie and Cone again

— Kyle Cogan (@CoachCogan) July 26, 2020

No one is looking at the QB. This is not zone coverage. pic.twitter.com/qUyf0GGPwl

There is a price to carrying so much in the way of play-calls and checks, as they only work if all 11 players know how and when to execute them properly. The smallest miscommunication can lead to disaster, meaning Saban and Smart are perfectionists who demand excellence at all times.

But the system also takes time to teach, meaning both programs must maintain a deep stable of talent at all times. Freshmen rarely play regularly and often only see the field in certain situations, no matter how talented they may be, as there is no substitute for practice reps in such a complicated system.

Clemson

Though he was one of the others credited with developing match coverage while working for Bob Stoops at both Kansas State and Oklahoma, Brent Venables has remained one of the sport's top defensive minds thanks to his adaptability rather than his reliance on one scheme or system. His Clemson defenses have become some of the nation's best every year, finishing sixth nationally last fall despite featuring one of his least talented units.

Four Clemson defenders heard their names called in last spring's NFL draft, even though cornerback A.J. Terrell was the only one of the quartet ranked among the top 450 players in his respective recruiting class. Safeties Tanner Muse and K'Von Wallace joined the ultimate hybrid defender, Isaiah Simmons, as unheralded recruits who thrived in Venables' system last fall as it had to replace four All-American defensive linemen from the prior year.

With a relative lack of overall talent compared to years past, Venables didn't double-down on what had previously worked. Rather, he became a master of disguise to sew confusion and provide cover for his defenders that didn't always have the advantage in one-on-one matchups.

Until the College Football Playoff, the approach largely worked without fail. Four times the Tigers held opponents under 200 total yards while only once allowing over 300 - to Virginia in the ACC championship game. Once the Tigers reached the final four, however, Venables could only disguise so much and Ohio State and LSU combined to gain 1,144 total yards against the Clemson defense.

"I try to figure it out week in, week out," Venables said of his efforts to make up for the lost talent from the year before. "To be honest, literally you try to come up with a game plan, try to help your guys, put them in a position to be successful. That sounds cliche, but that's really what we've done all year.

Justin Fields and Joe Burrow were able to diagnose the post-snap movement and identify favorable matchups as their talented offensive lines picked up the wide array of blitzes and stunts Venables sent their way.

But what sets Venables apart is his aggressiveness. Even as his team was lit up by the Buckeye offense in the first half of the Fiesta Bowl, he began blitzing even more and leaving his secondary exposed. Though the Tigers gave up quite a few yards, they also forced four sacks and two interceptions as Fields faced more pressure than he was used to.

This fall, however, the Tigers' strengths will flip, as the defensive line should provide cover for a young secondary, meaning the 2020 Clemson defense could like entirely different than the 2019 vintage. While it remains unclear what exactly this means for the Tigers' personnel and coverage packages, one thing is certain: Venables will try to dictate the flow of the game rather than sit back and react.

"There has to be strategy on both sides," he said of the chess match between opposing play-callers. "Why do they go tempo, no-huddle, why do they check the sideline. I'm just asking. So they can get in the best call based on the structure that you're presenting. We're trying to do the same thing. That's all we're doing, trying to counteract that."

Oklahoma

Though the Sooners have appeared in the past three College Football Playoffs, most believe that's in spite of their defensive performance rather than because of it. In Alex Grinch's first season in charge, however, the OU defense looked far better than in recent years.

Oklahoma gave up 356 yards-per-game in 2019, ranking just 38th nationally in that category. However, those numbers are skewed mightily by the 692 yards allowed to LSU in the CFP semifinal.

In the regular season, the Sooners led the Big 12 in total defense against conference opponents, surrendering just 324 ypg in the nation's most offensive-minded league. More importantly, that was Sooners' lowest average allowed in league play since 2009, showing both growth and potential.

To see these results, the former OSU assistant leaned heavily on a two-deep Quarters system which placed a heavy burden on the two safeties to act as playmakers. With the corners playing press-coverage outside, Safeties Delarrin Turner-Yell and Pat Fields finished second and third on the team in tackles by keeping their eyes in the backfield and playing downhill quickly, reminding many of the dominant Michigan State defenses from years past.

Additionally, Grinch gummed up blocking schemes by often stemming his down linemen -bouncing their alignment over one gap just before the snap and creating confusion across the offensive line.

While the safeties provided a great deal of support in the run game, they were also easy to isolate with RPOs. Grinch would often trade run support responsibilities between the safeties and outside linebackers from play to play, but the safeties' deep alignment gave opposing quarterbacks a quick read in the passing game instead of handing off.

While still not perfect, the Sooners have found a new identity with this Quarters system, which is something they'd missed for quite some time. It will allow them to recruit specific skillsets that fit the scheme while building upon the same set of fundamentals year after year.

The pieces appear to be in place for the Sooners to match their prolific offense, but it will take some time. However, the humiliating loss to the Tigers signaled to many outside of Norman that little had actually changed. Whether Oklahoma fans have enough patience to let that process play out is another question entirely.

LSU

We'd be remiss not to include the defending champions in this discussion, even though LSU has appeared just once in the CFP and must now replace the leader of its defense, Dave Aranda. The Tigers had long been a pipeline for NFL defensive talent, but until 2019 hadn't translated that talent into a title.

Aranda, now the head coach at Baylor, had been college football's highest-paid assistant after Texas A&M attempted to hire him away from Baton Rouge for the same position in 2018. Before heading south, however, Aranda made a name for himself by leading the Wisconsin defense which ranked first nationally in total defense, second in scoring defense, third in pass defense, and fourth in run defense during the three seasons in which he was in charge from 2013-2015.

Like the Alabama and Georgia defenses, Aranda's unit is technically a 3-4 scheme, though it largely functions like a single-gap 4-3 with the weakside end in a 2-point stance. What sets Aranda's system apart is his ability to disguise which four defenders will rush the passer and who will drop into coverage.

Much like the old zone blitzes that were popular among 3-4 NFL teams like the Pittsburgh Steelers, the Tigers will drop defensive linemen back into coverage and hedging the risk of sending multiple linebackers on a blitz. As detailed in the video below, the goal is not to get a free rusher running to the QB but to create mismatches in protection, such as a running back trying to block a pass-rushing OLB one-on-one.

With so many unknowns about what the defense is doing, offenses end up keeping the back or tight end to help with pass protection, limiting the number of options for where the ball can go. Thus, the defense's job becomes easier.

In many ways, the system most resembles that of Clemson, as it looks to create confusion in favor of the defense. Also like Clemson, LSU adapted its base 3-4 package into a 3-2-6 Dime package on many occasions, with the defensive end covering both B-gaps in an increasingly popular look known as a Tite front.

As noted by USA football:

Out of the Tite front, you can control B-gap to B-gap with three defensive linemen and one inside backer, basically leaving a free hitting linebacker that can track, stack, and fall back on any inside run. Stack, track, and fall back refers to the linebacker’s ability to track the path of the running back, and if he cuts back, the linebacker “falls back” to play the cut back because in the Tite front he is not responsible for an interior gap versus the run game. In essence, teams are attempting to eliminate the inside portion of offenses by any means necessary, but they are also doing so by not having to devote max resources and defenders into the middle of the defense.

Aranda's replacement, former Nebraska and Youngstown State head coach Bo Pelini, has been open about the fact this his defense will look somewhat different, mixing in more coverages than seen from Aranda's squads. But with the four other defensive assistants remaining on staff from the year prior, one can imagine that the Tiger defense should not, and will not, change too much in 2020.

Ohio State

After employing versions of match coverage and two-deep alignments for much of the CFP era, the Buckeyes went the opposite direction in 2019 and ended up with the nation's best defense statistically. While the rest of their CFP rivals rely on complex systems meant to disguise and confuse, OSU prefers relative simplicity.

On early downs, the Buckeyes were content to sit in their single-safety look, alternating between man-free coverage (Cover 1) and old school, spot-drop zone coverage (Cover 3). Unlike the zone-match schemes described above, Ohio State defenders don't run with receivers. Rather, they watch the eyes of the quarterback and rely on their superior athleticism and well-drilled fundamentals to break on the ball and make a play.

Additionally, the pieces of the zone are easily interchangeable, removing the need for complex adjustments and allowing defenders to play fast and without hesitation.

The system relies heavily on having superior talent at cornerback and free safety. These three are responsible for keeping everything in front of them and forcing passes underneath, regardless of whether the call was man or zone. With three veteran NFL-caliber talents manning those positions last fall, the scheme worked nearly to perfection.

Additionally, those defensive backs are protected best by a talented defensive line capable of creating pressure with just four rushers. With Chase Young leading the way, the Buckeyes had the perfect recipe for success.

Ohio State only allowed over 400 yards on two occasions, to Wisconsin and Clemson in the season's final two games. By that time, the Buckeyes' tendencies had become better known and the Badgers more than doubled their offensive output from their first meeting in late October.

Now, with a full offseason for opponents to dissect film of this dominant unit, opposing offenses will no doubt look to test a secondary replacing both corners and the free safety in man-coverage or testing the seams of the zone without fear of Young collapsing the pocket on his own. With the system's architect, Jeff Hafley, now at Boston College, the remaining staff and new DC Kerry Coombs must find new wrinkles to maximize this year's squad while keeping things simple.

While each team appears capable of returning to the CFP this winter, the Buckeyes seem to be taking a very different path on the defensive side of the ball.