Walter Camp: The great innovator.

Walter Camp: The great innovator.Last Friday Nebraska officially became part of the Big Ten Conference, completing a series of events that began last summer amid swirling rumors, big money deals, and threats. It seems certain that the conference will not be expanding again anytime soon, and so this might be a good time to look back on how it all began.

Many of you probably know that the Big Ten is college football's oldest continuously operating conference, and some of you might even know who the original 7 schools were (Chicago, Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Northwestern, Purdue, and Michigan) that started the league back in 1895, but how many know how the increasing violence of the sport led up to the formation of the conference?

It all began with a game between Princeton and Penn on October 25, 1884. Princeton's sophomore quarterback Richard Hodge came up with an idea for a play. He described the genesis of the play like this:

In the middle of the game, Captain Bird, of Princeton, had called upon Baker, '85, a halfback, to run behind the rush-line, which charged seven abreast down the field. It was an old play, and gained little ground the second time it was used. It suddenly struck me that if the rush-line would jump with the snap of the ball into the shape of a V, with the apex forward, we ought to gain ground. A consultation was held, and upon the next play the formation was tried, Baker plowing in the V to Pennsylvania's five-yard line, from which on the next play he was pushed over.

And so was born what became known as the "V-trick", a formation of seven players with arms locked and formed up in the shape of a V, with a ball-carrier inside. The play worked, and it helped turn a 0-0 game into a rout as Princeton won 31-0. Little did they know that they had begun a transformation of the sport into something so violent that rugby would look tame by comparison.

Princeton did not attempt the play again until four years later in 1888 against Yale, which was led by legendary coach and football innovator Walter Camp. Camp had pushed for such rules such as "possession" (only one team has the ball at a time), the idea of "downs" (as opposed to unlimited possession until a score), and new scoring rules for touchdowns and field goals (previously each was counted the same). Yale, Princeton, Harvard, and Columbia made up the original Intercollegiate Football Association that the schools formed in 1876. The IFA was the only rules-making entity with any power at the time, and Camp was unquestionably the most powerful person involved in that process.

Princeton's second attempt at the V-trick did not go as well as the first. Yale defensive lineman William "Pudge" Heffelfinger saw the formation and instantly figured out a way to attack it. He took a running start at the formation and leaped over the point man, crashing into the ball-carrier and smacking him to the ground. Yale thus successfully defended the play and won the game. Nevertheless, other teams copied the play and very soon the V-trick was being used all over college football. Not only that, but teams also copied Yale's strategy for defending it. The violent collisions that resulted from these tactics, collectively known as "mass-momentum" plays, created many injuries and even deaths. But the worst was yet to come.

In 1892, Harvard unveiled the latest and greatest of the mass-momentum plays, the "flying wedge". The play was the brainchild of Boston lawyer and chess expert Lorin F. Deland, who had studied Napoleon Bonaparte and was fond of military strategy. Deland had no football experience, but he was interested in the sport and he approached Harvard's coaching staff with his idea, which they finally implemented in the biggest game of the year. Against Yale in 1892, Harvard opened the second half with a kickoff, but in those days it was legal to just tap the ball and then put it in play by running with it or handing or pitching to a teammate. Using this strategy, Harvard implemented their devastating new weapon:

Deland divided Harvard's players into two groups of five men each at opposite sidelines. Before the ball was even in play team captain Bernie Trafford signaled the two groups. Each unit sprang forward, at first striding in unison, then sprinting obliquely toward the center of the field. Simultaneously, spectators leapt to their feet gasping.

Restricted by the rules, Yale's front line nervously held its position.

After amassing twenty yards at full velocity, the "flyers" fused at mid-field, forming a massive human arrow. Just then, Trafford pitched the ball back to his speedy halfback, Charlie Brewer. At that moment, one group of players executed a quarter turn, focusing the entire wedge toward Yale's right flank. Now both sides of the flying wedge pierced ahead at breakneck speed, attacking Yale's front line with great momentum. Brewer scampered behind the punishing wall, while Yale's brave defenders threw themselves into its dreadful path.

Of course, this was long before the advent of helmets, shoulder pads, face-masks, and all of the other protective gear that football players today routinely wear during a game. As a result of these mass-momentum plays, the violence in college football increased dramatically. The carnage was so widespread and so common that newspapers began including injury reports as part of their football coverage along with all of the other stats. Eventually, public sentiment began to turn against the mass-momentum plays, not only because of the violence but because spectators could not see the ball-carrier as he was surrounded by colliding players.

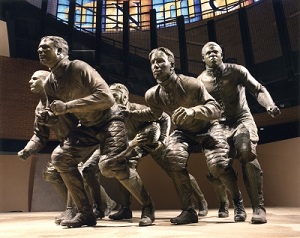

The Flying Wedge sculpture at the NCAA Hall of Champions

The Flying Wedge sculpture at the NCAA Hall of Champions

In 1894, the "Big Four" football programs of the time (Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Penn) met in New York to propose new rules designed to decrease the violence. One major rule that was passed was that a kickoff must travel at least 10 yards before it is in play unless it is touched by the opposing team. This rule made Deland's flying wedge kickoff play illegal, but it did not prevent teams from using mass-momentum plays in other situations. So the teams gathered again the next year to seek further restrictions. Princeton and Yale proposed a new rule requiring teams to have at least 7 players on the line of scrimmage on offense. Harvard and Penn disagreed, and they broke up the Big Four so that they could play by their own rules.

At this point, seven midwestern schools began meeting to discuss the formation of a new conference, and the result was what was then called "The Western Conference", formed with the schools mentioned above in 1896. In addition to addressing concerns about violence, the Western Conference schools were concerned about making sure that eligibility for playing football was restricted to only those who were actually enrolled in the schools. Many schools were using semi-pro players on their teams and the new conference immediately passed rules to put an end to that practice.

In 1899, Iowa and Indiana joined and people began referring to the conference as the "Big Nine". They lost Michigan in 1908, but gained Ohio State in 1912 and then finally became known as the "Big Ten" when Michigan returned to the conference in 1917. The birth of a competing conference motivated Penn and Harvard to reconcile with Yale and Princeton, bringing the "Big Four" back together in 1896. Afterward, they agreed on the seven-man line rule, along with other rules such as limiting when and how a player could move prior to the snap.

The new rules did not completely eliminate the flying wedge and other mass-momentum plays, but the sport had turned a corner and had put into place some processes that would continue to produce new rules and modifications to cut down on the brutality. These processes eventually lead to the formation of the NCAA in 1910, with a self-contained rules-making committee and 62 member schools. There was still a lot of violence, but now there was a governing body with the authority to make changes swiftly so that the sport would not end up fighting lawsuits or congressional investigations.

Today, the Big Ten has 12 member schools and sponsors 25 mens and womens sports. It has its own network that reaches approximately 40 million households nationwide. Big Ten universities provide more than $112 million in direct financial aid to more than 8700 student-athletes. It is a huge enterprise that has grown more powerful as it has added schools and media reach. But if not for the flying wedge and other such tactics, it may never have happened.