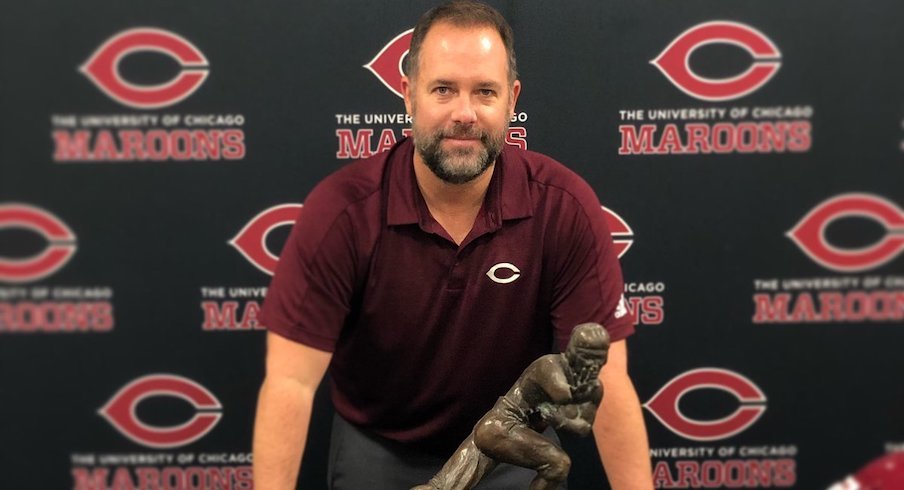

On one end of the phone was Brian Hartline, Ohio State’s 33-year-old wide receivers coach. Jared Still, a 42-year old in the nascent stages of his career as a college coach, was on the other side of the call.

To most whose only experience in the profession has come as a first-year assistant wide receivers coach in Division III at the University of Chicago, talking ball with a football lifer who spent seven years playing wideout in the NFL before becoming a standout position coach on Ryan Day’s staff might be a bit nerve-wracking.

Not for Still. Not for someone who’s spent the better part of the past two decades searching for his life’s purpose and feels as though he’s finally found it on the football field. Not after the innumerable twists and turns his life has taken.

“I think the 23, 24, 25-year old version of me would've been (nervous),” Still told Eleven Warriors. “But I'm 42 now, been through war and divorce and quite a few things in life.”

The conversation between the two spanned a wide range of topics. They talked about Still’s background and what brought him to coaching. They discussed leadership philosophies and wide receiver techniques.

Still had a few questions he wanted to ask, but the conversation went in somewhat of a different direction than he anticipated, which he didn’t mind. He says he was up front with Hartline about wanting to “just to be a sponge and take in what he was willing to teach.”

Hartline explained to Still his philosophy when taking over a position group. He noted the need to always be prepared, authentic and never ask players to do anything he doesn't do. They broke down the catch point, break point and alignments of wide receivers. Hartline said he understands players making mistakes but has "zero tolerance" for a lack of effort.

By the time it was over, they had already spoken for 25 minutes, marking the longest time Still had ever spoken one-on-one to a coach of Hartline’s caliber. And it began with a tweet.

On March 17, he fired off a message on Twitter to Hartline and quality control coach Keenan Bailey saying, “I’m pretty new to coaching WR’s - and want to learn from the best - is there any way I could come to Columbus and spend some film time with you guys?”

He didn’t have to wait long to hear back from Hartline. Three minutes later, Hartline responded with a quote tweet of his own, telling him to send a direct message.

That would be a little tough currently, but you can DM me and I can hop on a call with you.#Buckeyes #BeDifferent https://t.co/K7neaRI0jw

— Brian Hartline (@brianhartline) March 17, 2020

“I mean, what’s the worst that can happen?” Still said. “They probably just don't ever see it, or they do and I don't know. I was pretty stunned by him just sending him a DM and saying, ‘Here's my cell. Give me a call when I can.’”

Since concerns about COVID-19 had led to the closure of the Woody Hayes Athletic Center’s football facilities, Hartline couldn’t invite him to Columbus to sit in the back of the film room or watch practice from the sidelines. Instead, he gave him a half-hour on the phone.

“I will remember this the rest of my career and be intent on paying it forward whenever I have the opportunity to do so.”– Jared Still on his conversation with Brian Hartline

Like the coaching journey Still has begun, the beginnings of this interaction couldn’t be described as conventional. But that’s become the norm ever since leaving his sales job to coach Division-III football a little more than a year ago.

“He encouraged me a lot when he heard after my first year not getting paid really anything – I had a small stipend a couple months,” Still said. “But that I loved it so much and that I loved the guys. He's like, ‘You're going to be great in this.’ He said some people just coach because that's what they do and what they've always done and where their life went.

“He said you certainly had enough other perspectives to know what you want to be doing by that point. Got that right. Got that right.”

Hartline was 9 years old when Still enrolled at Northern Arizona in 1995, giving him his first dose of college football. He played two years at the FCS level, but without any post-college plans to stay in the game, he gave it up after his second season.

Instead, leaving the sport behind, he joined the Air Force after graduating in 2000. Wanting to choose something that would both pique his interest and translate to the private sector, Still went into contracting. Sometimes, that meant he worked on major long-term projects, including the F-22 program or the Joint Strike Fighter program. Other times, he focused on day-to-day tasks, such as logistics or maintenance.

Still, who was in Japan during the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, didn’t return stateside until 2003, yet he wasn’t ready to move on from the military. In January 2004, he volunteered to go to Iraq, where he worked as a contracting officer until July 2004. On a weeks-long hiatus in the United States before redeploying to Iraq, his plans suddenly changed when he broke his collarbone while riding motorcycles.

By the time it healed, those Still was with in Iraq weren’t there anymore. In 2005, he separated from the Air Force, getting awarded a Bronze Star Medal, which he calls the “greatest honor of my professional life.”

His next step? He wasn’t quite sure.

“Really (I) kind of was chasing this sense of mission and purpose and serving and, of course, adrenaline that I felt in Iraq in ‘04,” Still said. “I really chased that for a long time.”

He began in the corporate world, then bounced over to the start-up world for a while before returning to the corporate side. He moved from southern California to Texas and got married.

A connection with a friend who had two-and-a-half decades of youth coaching experience led him to begin the process of becoming an agent. His buddy had referred a few of his former players to Still. But that never came to fruition.

“Then things really kind of blew up in my personal life,” Still said. “I was basically kind of struggling from there. I landed on my feet in another good job, a sales job, and started making some money. But I was really searching for that purpose again.”

That purpose, he eventually realized, came in the form of coaching football.

Hal. Freakin. Mumme. telling stories of his first OL Coach - a guy named Mike Leach. pic.twitter.com/aoalRCXbfF

— Coach Still (@jaredstill) June 22, 2019

He read Urban Meyer’s “Above The Line” book, becoming fascinated by the former Ohio State head coach, and more recently started listening to his “Focus 3” leadership podcast with Tim Kight. He studied Bill Belichick, Nick Saban, Hal Mumme and the history of the sport. Essentially, as he put it, he “re-fell in love with the game of football.”

Still started going to football clinics in North Texas, visited the NFL combine and met with his former Northern Arizona coach, Robb Akey, who’s now Central Michigan’s defensive coordinator. At every stop, he told those in the coaching sphere that he just wanted a chance.

Assistant coach, analyst, whatever. It didn’t matter.

“I was at a good sales job making fine money and I was miserable every day, and all I wanted to do was read, write and talk football,” Still said.

At the University of Chicago, he finally got his chance. After finding a job posting on Football Scoop, applying and interviewing for it, he got an offer to become an assistant wide receivers coach and accepted it.

As a first-year coach in 2019, Still did all the “grunt work,” as he put it. He set up, then took down, the video tower and sideline camera every day. He labeled plays after practice and restocked fridges with post-workout smoothies some nights before early morning lifts.

The tasks might not be described by most as particularly fun, but the year in Chicago only heightened his sense that this was the industry meant for him. Still, though, had somewhat of a location issue.

“My youngest daughter just turned 10,” Still said. “After the season, when things kind of fully slowed down and we went into the holidays, my heart really started to ache to get back to Texas and close to her.”

Abbys Official Coaches Kid Photo (SMU is hosting the N. TX HSFBCA Clinic) pic.twitter.com/cFMpAmy7EK

— Coach Still (@jaredstill) March 4, 2020

Willing to go the high school coaching route if necessary, Still managed to land a job as a special teams quality control coach at an FCS program. He didn’t want to publicly disclose the school until it became official, but it's in Texas.

“To go from a desk to Division I in 12 months is pretty crazy,” Still said. “I just couldn't be more excited.”

Older yet less experienced than many coaches at all levels of football, Still understands there’s a natural gap between him and others in the industry.

“They're most likely going to know a lot more ball than me,” he said.

Yet having read so much about football, consumed so much content from coaches and studied the game for the better part of the past decade, he’s fiending for as much as he can learn from coaches at the highest level. Once the offseason began, he decided to set up plans to attend clinics and go to the coaches association for the first time.

Also, he wanted to individually hear from some of the guys he’s long looked up to.

“I'm just going to reach out to guys I've heard and everything that I've read, listened to, are really the best technical experts at the position,” he told himself.

That led him to Hartline. Not only has he become a respected position coach, but he also worked under Meyer as a quality control coach then interim wide receivers coach.

“Anyone from that sphere of influence, I want to talk to,” Still said. “But coach Hartline is a technician.”

Hartline, Still realizes, didn’t have to give him a call. Sure, his schedule’s a bit different since he’s spending most of his hours at home instead of coaching Ohio State's spring practices, but he didn’t need to respond.

Instead, he got back within three minutes and called him the next night. To Hartline, it might have just been a 25-minute phone conversation during an otherwise busy day. To Still, though, this was the latest motivator in a burgeoning coaching career.

“I will remember this the rest of my career and be intent on paying it forward whenever I have the opportunity to do so,” Still said.