In an era where shotgun spread formations have become the norm at every level of the game, a select few offenses stick out like sore thumbs in the current college football landscape.

As Urban Meyer and his staff look toward their upcoming fall schedule, their eyes may be drawn first to names like Oklahoma, Penn State, and Michigan, immediately noting the talent on each of those rosters. However, another matchup early in the season surely gives the Buckeye coaches reason for pause at this point on the calendar: the Sept. 16 tilt with Army.

Like the other service academies, the Black Knights run a flexbone option system that is rarely found at the FBS level, meaning defensive coordinator Greg Schiano has surely begun preparing for the unique task of stopping such an attack this offseason.

While the Air Raid offenses of Hal Mumme and Mike Leach caught the imaginations of many during their rapid ascent to the mainstream in the 1990s, a similar fascination came with spread-to-run systems like that of Urban Meyer or Randy Walker in the following decade. Similarly, today's flexbone outliers can trace their roots to one man: Paul Johnson.

Johnson is considered to be the 'Godfather' of the flexbone, inventing the system on the fly during a stint at Georgia Southern in the mid-1980s before installing it at the Naval Academy years later. After seeing their arch-rivals find nearly two decades of relative success, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point decided to follow suit with the hiring of one of Johnson's proteges, Jeff Monken, in 2014.

Monken began his coaching career as a graduate assistant for Johnson at Hawaii while the latter was the offensive coordinator, but after a handful of stops around the country, Monken joined Johnson's staff as the running backs coach at Georgia Southern in 1997. From there, the duo moved on to Navy and Georgia Tech before Monken left to become a head coach for the first time back at GSU in 2010. Current Navy coach Ken Niumatalolo and Monken worked closely together on those same staffs, learning every intricate detail of the run-based offense from its inventor.

This offense's roots were a bit of a happy accident, as Johnson described in a 2015 coaching clinic:

In 1983, I went to Georgia Southern as a defensive line coach. We were a run-and-shoot offense running out of the double slot. I moved to that offensive side of the ball in 1984. After that season, the head coach came to me and told me he wanted to get into the I-formation.

That was during the Herschel Walker era at Georgia. That was the trend in football. In 1985, we played our first three games in the I-formation. We did not have a fullback or a tight end or any of the personnel you needed to run that offense. I went to him after the third game and told him we needed to get back to the run-and-shoot because we did not have the players to play I-formation football.

Johnson, like nearly every other college coach at the time, was familiar with the wishbone and veer option offenses made famous at places like Texas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma, in which the QB often made two option reads on the same play, then lined up and did it over and over again. Johnson initially called his offense the 'Southern Veer' as it was his take on those aforementioned systems, instilling the same blocking and option concepts, except now it moved the two halfbacks to be flexed out like wingbacks outside the tackles, taking advantage of the run-and-shoot personnel he had on hand.

With the limited talent at his disposal, Johnson wanted to dictate the pace of the game and not allow the defense to force his team into any uncomfortable situations. As he noted in that same clinic speech,

In the double-slot formation, you have four receivers in the formation. It is an effective passing formation. The formation dictates how the defense will play. The offense takes the entire specialist groups out of the defense. We do not play against nickel and dime packages. In our offense, we do not worry about blitz pickup schemes. This offense controls the blitzing game. When you play 'assignment football' it takes away the blitzing game.

We gain a numbers advantage over the defense because of the blocking scheme. We can adjust the formations to gain advantages on the defense. In this offense, the offensive line has excellent blocking angles. The big thing about this offense is you do not have to block everyone.

Most defenses today have personnel that you cannot block. That suits our scheme perfectly. If you have a stud, we are not going to block him. We will read him and whatever he does is wrong.

While the playbook includes a number of other concepts, like inside traps, midline options, and good, old-fashion toss sweeps, the triple-option is most certainly the system's foundational concept.

On the play, the quarterback follows the same rules as those from the old 'wishbone' schemes of the 1970s, counting defenders to either side. The first defender to the outside of the offensive tackle is the handoff key on the B-back's (fullback) dive. If the QB doesn't handoff to the B, the second defender outside the tackle becomes the read man for him to pitch to an A-back coming from the backside, or keep to run for himself on the outside.

As seen last fall, the Cadets in West Point are well versed in the intricacies of this concept, with each move rehearsed to perfection:

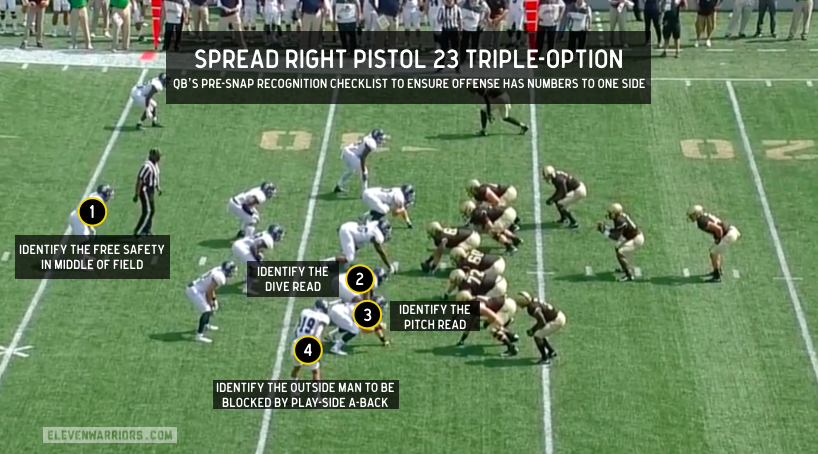

While this may appear to be a complex ballet at first glance, the rules for each player are fairly well defined and made clear before the ball is ever snapped.

As the offense reaches the line, the quarterback is already making his first read, locating the free safety to see if the defense has lined up evenly with an equal number of players on either side of the formation. If they haven't, the QB will make a call to flip the same play to the weak side.

Once the direction of the play has been finalized, the QB will then look for the two option reads on the play, counting from the first player outside of the tackle.

Finally, he'll identify the outside player (often a cornerback or outside linebacker) who is to be blocked by the play-side A-back. In this example, the A has gone in motion just before the snap before turning back in the direction of the play and making this crucial block.

Of course, that A-back isn't the only player looking to identify who he'll block on the play, as this certainly isn't the kind of scheme that asks the offensive line to just block whoever is in front of them. While the center and both guards get to do just that on this play, cutting off the nose guard and two of the three linebackers respectively, the play-side tackle and the tight end have far different responsibilities.

The tackle makes an initial punch to the defensive end being read on a potential pitch before quickly releasing upfield and sealing the outside linebacker back inside. Meanwhile, the tight end releases off the line and actually makes his way to the free safety, keeping that defender from attacking downhill unblocked.

As you may have noticed, the play-side defensive tackle (lined up on the outside shoulder of the tackle here, more like a 3-4 end) is left completely unblocked. That doesn't mean no one is accounting for him, though.

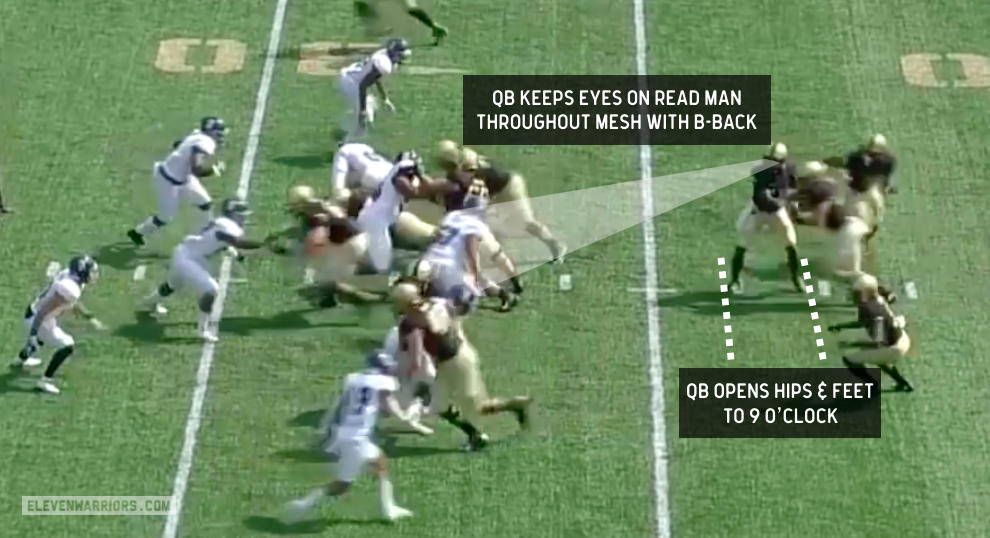

As soon as the ball is snapped, the quarterback immediately opens his hips and gets both feet in the ground at a 90-degree angle, holding the ball out for the B-back but never taking his eyes off the optioned DT. The B-back's first job is to get to the ball, regardless of where the QB has put it, but once there, he's also reading the defender in question.

While the quarterback is reading the defender to decide whether to give or keep the ball, the B is reading him like a ball-carrier, waiting to see where a potential hole may open in his direction. In this example, though, the defensive tackle closes directly on the potential handoff, leading the QB to pull the ball back, step around the traffic, and get outside while he looks for the next defender to read.

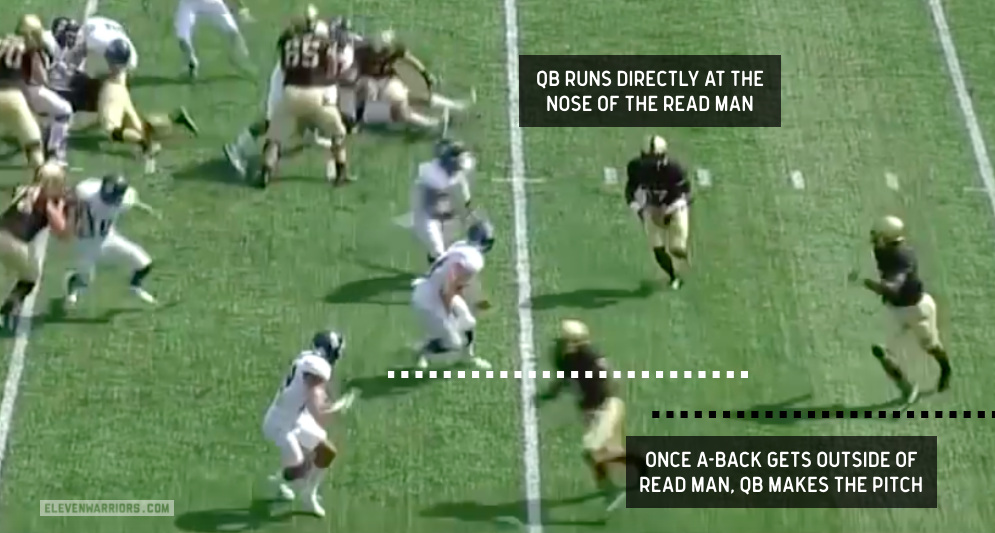

With the unblocked defensive end clearly in his sights, the quarterback runs directly at him, aiming for the player's nose and hoping to force him into a decision. If the end ever turns his shoulders inside, seemingly looking to make a play on the ball, the quarterback will immediately slow down, step off track in which he was headed and deliver his pitch outside, looking to avoid a hit instead of waiting until the last second.

But as long as the read man keeps his shoulders parallel to the line, the quarterback will hold onto the ball, waiting to either get outside the traffic and find a crease to cut upfield, or for the A-back to coming from the backside to get outside the defender. While the end is patient enough to wait for some help from his teammates to get off their blocks in this example, he fails to feather out the A-back, allowing him to get a step outside on his way to picking up a 33-yard gain.

Monken enters his fourth season at West Point this fall, meaning his senior class will have spent all four years mastering the flexbone offense. The result of their hard work finally emerged on game days last fall, as the Black Knights went 8-5, beat Navy for the first time in 14 years, and won a bowl game. Now, with a senior quarterback under center in Ahmad Bradshaw, they'll look to upset the Buckeyes in what will easily be their toughest matchup of the 2017 season.

Perhaps even more importantly, while the Cadets have mastered the flexbone in their time on campus, few players on Ohio State's roster have ever seen an offense like this in person. Only Chris Worley remains from the 2014 defense that took down Navy in a 34-17 victory to open the season. Meanwhile, both architects of the defensive effort that day, Chris Ash and Luke Fickell, have left the program to take head coaching jobs.

Luckily, Schiano went 5-2 against Johnson's flexbone triple-option during this stint in charge of Rutgers, meaning he knows what it takes to shut it down. However, as Johnson, Niumatalolo, and Monken have shown for years, that's easier said than done.