He is discharged from beyond the grave to mock us.

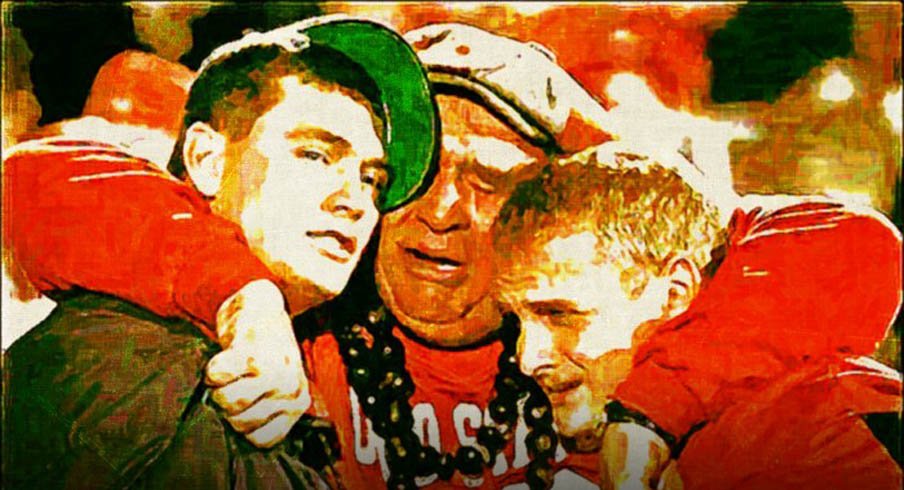

The snapshot is from the aftermath of that impossible loss to Michigan State in 1998. It's the only evidence of any sound in the stadium that night, as most of the 93,595 shellshocked fans who wandered out onto the streets did so without saying a word.

That afternoon the Buckeyes had a 24-9 lead, and then a punt hit Nate Clements in the back. Something strange then happened to the air on the field: Guys who never fumble fumbled. Every jump ball, every 50/50 play and every single break went the Spartans' way, yet the most dominating Ohio State team since 1968 was still in position to win on the final play.

But it did not. The crying man was one of many grown men who openly wept that evening. A camera found him amidst the confusion following the game - but that was only because a camera always found him.

He now shows up after every loss, however rare those may be. Go ahead and Google crying Buckeye fan and you'll find the photo above hosted on Michigan blogs, message boards and everywhere else you would expect to find people relishing in any Ohio State setback. He reappears every time the Buckeyes lose.

His image is sought and presented with hurtful intentions, though anyone who actually knew him might find comfort in seeing him openly weep for Ohio State football - because he did it all of the time.

The crying man has been dead for a decade now. He had a name. It was Orlas King.

My father's Ohio State tickets were in B-Deck for ten years. I still absolutely loathe B-Deck even though our old seats no longer exist, thanks to stadium renovations. That section received shelter from the elements at the deep expense of game experience.

Due to the overhang we had no view of the scoreboard. What happened to a football once it left the punter's foot or a quarterback's hand was a mystery until it reappeared on the back end of its arc. Our section of B-Deck basically watched football games through a letterbox tunnel. The roar of the stadium came from mostly obscured fans above us, as C-Deck was merely a rumor when you sat beneath it.

However, we had an immaculate view of a giant concrete pillar to our left, and our seats were directly across the Horseshoe from The Neutron Man's. This meant every time the band queued up the Pointer Sisters' swan song we were treated to a Rockwellian image of Orlas King high-stepping with his finger guns, asymmetrically framed by the backsides of thousands of heads turned in his direction to take it all in.

I cannot forget the day I solved what the Neutron Man was all about: It was October 15, 1988. Ohio State was on its way to losing a third-straight game, this time at home to Purdue. They were going to be 2-4 in John Cooper's first season and I had begun to detach myself emotionally from the team in order to better cope with the inescapable fact that the Buckeyes...just really sucked.

I wanted to love anything as emphatically as Neutron Man loved Ohio State.

As the game wound down and the unfortunate outcome began to reveal itself, the band struck up Neutron Dance one final time. I remember thinking man, who wants to dance right now? My eyes, along with thousands of others immediately turned toward where the Neutron Man was situated, as everyone always knew where that was. Orlas immediately popped up out of his seat and began happily shaking his ass as if the Buckeyes were up by 56.

It made me feel better. Surely he was as miserable as we all were watching that Buckeye team lose at home to Purdue (a week earlier it was humiliated in Bloomington) but I think he understood that his tribe depended on him. It wasn't just the football, the cheerleaders, Brutus or the band; he had become part of the show every Saturday over the previous decades.

Orlas pocketed his disappointment for those 45 seconds and did his dance for everybody as the Buckeyes prepared to lose once again. For about a minute, the Buckeyes didn't suck anymore, as the Neutron Man's moves briefly shielded us from that reality.

I was detached teenager, catatonic and wrestling with an epiphany: I wanted to love anything as emphatically as Neutron Man loved Ohio State.

Orlas was known as the B-Deck Dancer until Beverly Hills Cop hit the theaters and launched Neutron Dance into the national consciousness, FM radio's pop music echo chamber and ultimately Ohio State home games.

The song fit him like nothing else the band had ever covered before, and the sight of a middle-aged man in a jersey, beanie and dad shorts dancing to Pointer Sisters as if no one was watching him was just too much. The joyous chant began and spread throughout from the rest of the stadium: Neu-tron Man! Neu-tron Man! Neu-tron Man!

The B-Deck Dancer had found his opus, and it quickly became his moniker. He didn't name himself - the stadium did.

He danced when he wanted to as well as when he knew he had to - even when he probably didn't feel like dancing. More importantly, Orlas didn't seek out and find cameras intent on spreading his brand. Instead he went to fans, students, blue-hairs - everyone - and implored them to make a difference in the game's outcome, whether he was in Ohio Stadium for a nationally-televised contest or at a high school game without cameras. Be louder. We can win this!

Neutron Man was an interested spectator, but more than that - he was a heavily-invested emotional stakeholder who took being a Buckeye fan very seriously. He wasn't interested in seeing Ohio State's home field advantage being squandered to seated comfort or entitlement. Fans have a purpose. They can help determine the outcome.

he redirected all of the attention he was receiving to the cheerleaders and the band.

Once his celebrity began to grow to the point where it seemed overwhelming, he redirected all of the attention he was receiving to the cheerleaders and the band. He used that popularity to raise money to fund cheerleading scholarships, because cheerleaders have a noble purpose: They can help determine the outcome of the game.

The term superfan has taken on a negative connotation as of late within Ohio State circles due to the perceived intent of these guys who dress up in their own costumes, hunt for television cameras and openly engage in self-promotion. At least one of them has appearance fees - if you would like him to show up at your tailgate.

But there should be no confusion about what Neutron Man's intentions were. Ohio State had to win every Saturday, and he firmly believed he could contribute to that materializing. That's what superfan really means.

Everything you've ever heard about the Rose Bowl and Pasadena is true, but it's something you cannot adequately capture through television, creative language or glossy photographs.

You have to stand there, see it, breathe the air and feel the ambient energy to understand that this setting - for a football game or anything else - is perfection. There is no better college football venue on this planet or any other.

The Buckeyes have played in Pasadena twice this century; once in the 2010 Rose Bowl against Oregon and the other in Jim Tressel's second game as head coach, against UCLA. That one was originally scheduled to be his third game, but 9/11 abruptly cancelled the September 15 slate. Two weeks after terrorists used airplanes as weapons of mass destruction Ohio State boarded one for Los Angeles.

I also made it to LA that week, though when you're named Ramzy Nasrallah and airport security screening is as primitive as it was in 2001, you receive what can be kindly described as an extended security check. I sheepishly stood in O'Hare Airport at 6am - three hours before takeoff, as travelers had been instructed - between two uniformed soldiers carrying machine guns as agents rifled through my belongings while my friends helpfully shouted let him go he's more American than you at them.

"Dude, I told you to put porn and ham in your carry-on!" Screamed one of my friends as soon as the TSA deemed me a non-threat. "You would have been through there in like 30 seconds." Truthfully, I had changed my laptop wallpaper to an American flag but stopped short of over-Americanizing my belongings.

Two days later we were reliving the merriment of my security woes with new friends we had just met, with the San Gabriel mountains as a backdrop. It was the early morning of Saturday, September 22nd. Football had been halted for two weeks during a football month, 9/11 had shattered everyone's spirit and we just really needed a game.

We were already soaking in sunshine and cheap beer, trying to feel normal again. Afroman's Because I Got High was blasting out of every tailgate within earshot. Cavity search was being said where I was standing a little too frequently, with accompanying laughter at my expense.

I lost interest in the story as it was being told and my eyes wandered around to other tailgates nearby. They stopped on three men tailgating with the absolute barest of necessities, which meant they were standing around a keg of beer and nothing else.

One of them was a middle-aged man in a jersey, beanie and dad shorts. His cherubic face was aimed skyward as he vociferously finished off the beer in his red plastic cup.

"Holy shit," I said, interrupting the story about me. "It's Neutron Man." The group looked over and saw him addressing their keg. I walked over to meet him in my white #5 jersey. I introduced myself and told him about my epiphany from 1988 Purdue game when I could tell he didn't want to dance and thanked him for everything he does. He seemed to appreciate it.

"You know," he told me, "you look like Sammy Maldonado in that #5 jersey." During that period this was something I heard every time I wore the number five. The highly-sought after running back from New York never really caught on in Columbus, but at the time everyone couldn't wait to see Sammy the Bull finally break out. We share similar faces and skin tone, apparently.

"I am Sammy Maldonado," I whispered. "Just going to finish this beer before I head in for warm-ups."

Neutron Man roared like it was the funniest thing he had ever heard. "Well hurry up!" He shouted. "You're wasting time!" I finished off the beer I was drinking, quickly dug into my pocket for my keys, poked a hole in the base of the unopened can of lukewarm Natural Light I was also holding - and promptly shotgunned it to the boisterous cheers of Ohio Stadium's most famous dancer.

It was a role-reversal I'll always treasure: The man that I and the rest of Ohio Stadium cheered on every Saturday was now cheering me on. September of 2001 was an incredibly stressful month for everybody, let alone for those of us who got back into airplanes as soon as we were allowed to. Those breakfast beers with Neutron Man were the first time things just felt normal again.

As great of a release as the morning was, the Buckeyes stunk up the field a few hours later, losing to UCLA and revealing that 2001 would be a transitional struggle. Still, everything you've heard about the Rose Bowl and Pasadena is true. The entire day was immaculate, outside of the football being played by the visitors.

But for about a minute that day the Buckeyes did not suck. The Neutron Man briefly shielded me from that reality.

Orlas' father used to take him to one game a year when he was a child. It was his favorite day of the year. Like so many of us - me included - it was his father who introduced him to the cultural importance of fall Saturdays. You go down to campus and you get to be young again. Decades pass and your father still always sits right beside you, even when he isn't there.

Neutron Man died in the middle of a three-game losing streak in 2004, right when we needed him the most. The last Ohio State football he ever watched was Northwestern's only win against the Buckeyes over the past 40 years. He woke up in his condo in Florida the following week, ate his breakfast and then waited for the rest of his golfing foursome to arrive. They found him in the kitchen.

He was mourned for weeks. The band played Neutron Dance and everyone looked toward his seats, hoping he would still be there. Ohio Stadium had lost its only true bleacher act, and no one dared to replace the B-Deck Dancer who had openly cried after the Buckeyes lost to the Spartans in 1998.

Neutron Dance STILL belongs to him. The POINTER SISTERS' VERSION IS RELEGATED TO THE FORGOTTEN HITS OF THE 1980s.

If there is one way to remember Orlas King, it's in the throes of his signature happy dance. That song still belongs to him. The Pointer Sisters' version is relegated to the forgotten hits of the 1980s.

But if there is a second way to remember him, it's in full-blown tears. That's the thing about that famous photo that's repeatedly circulated with unkind intentions: Neutron Man cried all of the time.

He cried openly in November 1996 in Bloomington after Matt Finkes clinched Ohio State's berth in the Rose Bowl, and wept in public again the following week when the undefeated Buckeyes pulled off yet another magnificent collapse against 17-point underdog Michigan. He cried when he sat in Ohio Stadium on his favorite day of the year with his father as well as during all of the games he attended as an adult with his father beside him, even when he wasn't there.

He cried when Ohio State beat Miami in Tempe and he cried when that winning streak ended the following season in Madison. As it turns out, that famous photo of him isn't unkind at all. It's a tribute to a man who loved Ohio State more than many people love anything.

So while Orlas may be unwillingly discharged from beyond the grave with the intent to mock Ohio State fans, he ends up doing the opposite. That image isn't hurtful at all. If anything, it's comforting. Sure, Buckeye fans cry when the football team loses - but we do the exact same thing when they win too. We just care that much.

And the crying man is a reminder that Ohio State is fortunate enough to have fans who still dance, even while the Buckeyes are losing.