When the Big Ten announced Aug. 11 that it was postponing its fall sports season, it looked like the months-long debate over whether the Big Ten would play football this fall had come to an end.

Instead, it was only just beginning.

One full month after the Big Ten made that decision, the debate over whether the conference should play football in 2020 remains as intense as ever. The odds that Ohio State and the rest of the conference’s teams will play this fall has actually increased, but the Big Ten still hasn’t provided any public clarity on when the postponed football season will be played or what it will look like, and it’s still as uncertain as ever what will happen next and when we will start getting answers, though it is possible a vote on returning to play could be held as soon as Sunday.

Some things have changed in the past month – which is why we’re now talking about the possibility of Big Ten football being played by the end of October, when it initially appeared a month ago that no Big Ten football would be played before January – yet some things remain the same. Both have played a point in getting to where we are today, as the fight continues between those trying to save the season and those who believe it isn’t safe to play football right now, all the while frustration continues to mount amid the ongoing uncertainty.

Communication from the Big Ten remains minimal

This has been the most universal complaint against the Big Ten since the day the conference postponed the season, and that criticism has only grown louder over the past month. The Big Ten’s rationale for postponing the season was unspecific in the first place, and the conference has said very little ever since, even to those who are most directly affected by the decision.

Since its initial statement announcing the postponement on Aug. 11, the Big Ten’s only public comments have come in an open letter on Aug. 19 – which provided some additional details on why the season was postponed, but minimal details on what would happen next – and four small statements, which you have to look to find on the conference’s website, responding to the Nebraska players’ lawsuit against the conference, Kevin Warren’s conversation with Donald Trump and a letter written to the conference by several politicians in Big Ten states earlier this week.

Warren has not had a press conference in the past month, with his only comments coming in private one-on-one media interviews and in a Sports Business Journal interview in which he was asked one question about postponing the season. Many of the university presidents who ultimately made the decision not to play this fall haven’t spoken publicly about the decision, either.

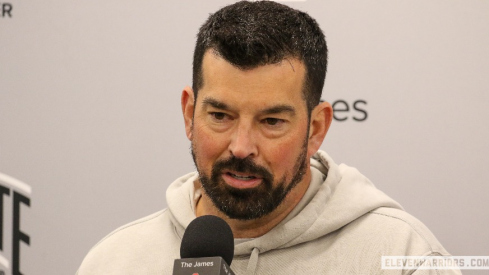

Most problematically for the Big Ten, it isn’t just fans and media who have been frustrated by the lack of communication, but players, parents and their coaches – leading to pointed comments against the conference by both Ohio State coach Ryan Day and Penn State coach James Franklin on Thursday. Day said Thursday that while he understood the “decision to postpone the football season because of health and safety considerations, the communication of information from the Big Ten following the decision has been disappointing and often unclear.” Franklin said Thursday that Big Ten coaches “just haven’t gotten great communication from the beginning.”

“We’ve never really been told or understood why the season was shut down in the first place, and there hasn’t been a whole lot of communication since,” Franklin told ESPN Radio. “When I say communication, we’ve had meetings, but I’m talking about really understanding ‘why’ and ‘what’ and ‘how we got here.’”

— Ryan Day (@ryandaytime) September 10, 2020

The wave of sports being canceled screeched to a halt

Even though there was an immediate sentiment among many that the Big Ten acted too soon when it postponed the season one month ago, it also seemed like a very real possibility at the time that no one would play college football this fall anyway. The Pac-12 postponed its fall sports on the same day, which left just six Football Bowl Subdivision conferences still playing this fall.

But the cancellations from those conferences never came, as all six of them – as well as some Football Championship Subdivision teams who are playing limited schedules this fall – have now either started their seasons or remain on track to later this month. Every major professional sport in America has now returned to action, too; the NFL opened its season on Thursday after getting through training camp with minimal positive COVID-19 tests, while the NBA and NHL playoffs have run smoothly and the MLB season kept rolling despite having to postpone some games.

High school football is also now being played in most of the country, including Ohio and several other Big Ten states, and early data hasn’t shown indications of significant increases in COVID-19 cases linked to those games being played.

All of that gives the Big Ten reason to reconsider its decision, as it provides evidence that sports can be played during a pandemic if proper precautions are taken. And while the Big Ten might have initially hoped that the College Football Playoff would be pushed back if the other major conferences also postponed their seasons, that hasn’t happened, and Ohio State and the rest of the conference are now at risk of losing their opportunity to compete for a national championship if their season does not start by October.

“Duke is playing Notre Dame, and Clemson is playing Wake Forest this weekend. Our players want to know: why can't they play?” Day said in his statement Thursday.

Public pressure opposing the season’s postponement has increased

After months of quiet uncertainty and conversations behind closed doors, Big Ten football coaches and players and parents started to speak out about their desire to play this fall in the last few days before the conference pulled the plug on the season. By that point, however, it was too late; the conference’s university presidents and chancellors had already made up their minds to vote for postponement, and they weren’t swayed by petitions from players, open letters from parent groups and pleas not to postpone by Day, Franklin, Michigan coach Jim Harbaugh and Nebraska coach Scott Frost.

In the month since the postponement was announced, however, the public backlash against the conference’s decision has been unrelenting. Day, Franklin, Frost and Harbaugh have all continued to express their opposition to the conference’s decision. Ohio State quarterback Justin Fields started a petition to reinstate the fall season that received more than 300,000 signatures. Parents of Big Ten football players, led by Shaun Wade’s father Randy, held a protest outside conference headquarters in Rosemont, Illinois, and parents of Ohio State and Michigan players both held protests on their own campuses, as well. Program staffers like Ohio State director of player personnel Mark Pantoni have publicly questioned the Big Ten in unprecedented fashion on social media.

Perhaps most impactfully, eight Nebraska football players filed a lawsuit against the conference that has already made the Big Ten release the results of its vote and will force the conference to provide even more documentation on the vote and its conference bylaws to the Lancaster County District Court by Saturday.

As aforementioned, politicians have even gotten involved in trying to convince the Big Ten to play this fall. The White House remains in communication with the conference, with Trump still publicly encouraging the Big Ten to play, while a group of 10 state representatives from Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin sent a letter to the conference on Tuesday calling on the Big Ten to “work with the leadership at our universities to allow sports to continue safely this fall.”

Dave Yost, the attorney general for the state of Ohio, told multiple media outlets this week that he will recommend Ohio State take legal action against the Big Ten if no season is played this fall. Nebraska attorney general Doug Peterson sent a letter to Warren on Friday claiming the Big Ten is noncompliant with the Nebraska Nonprofit Corporation Act.

If the Big Ten decides to play fall football now, the conference will be seen as bowing to public pressure, and that’s a perception the conference would probably prefer to avoid. But the groundswell of vocal opposition to the decision, including from powerful figures both within the Big Ten and outside the Big Ten, has become impossible to ignore.

Fall football is back in the conversation

When the Big Ten initially moved to postpone the season, it was implied that the conference would play football no sooner than January and that the option of playing at any time this fall was completely off the table. Initially, the conference appeared to be targeting a January return to the field – which Day pushed for at the time, believing it was the soonest the Big Ten would consider playing a season – while it was also possible the conference wouldn’t play until the actual spring.

Two weeks ago, it started to become clear the timeline was being accelerated, when multiple reports emerged that the conference was weighing the option of starting the season in late November around Thanksgiving. Now, it’s expected the conference will vote at some point in the next week on the possibility of playing in October, a possibility that gained more credence when Day said Thursday that the Big Ten’s medical subcommittee “has done an excellent job of creating a safe pathway toward returning to play in mid-October.”

Whether an October season or even a November season will actually come to pass is still up in the air, but there is evident momentum toward playing at some point this fall – ideally early enough for conference teams to be playoff-eligible, but at least early enough so the conference isn’t playing two full seasons in one calendar year – rather than waiting until 2021.

More players have opted out

Even before the Big Ten postponed the season, a few of the conference’s biggest stars had already decided to opt out. Minnesota wide receiver Rashod Bateman, Purdue wide receiver Rondale Moore and Penn State linebacker Micah Parsons all announced during the first week of August that they were moving on to begin their preparations for the 2021 NFL draft, just as numerous other top prospects have done even in conferences that are playing this fall.

Since the announcement, though, even more Big Ten stars have decided to opt out of whatever season might happen this fall, including Michigan cornerback Ambry Thomas and offensive tackle Jalen Mayfield and Northwestern offensive tackle Rashawn Slater. Ohio State lost its first player to opt-out on Friday when Wyatt Davis announced he was leaving the Buckeyes to begin his preparation for the NFL draft.

Those opt-outs themselves haven’t changed the equation for the Big Ten, but they are an indicator of what’s likely to come if games aren’t played this fall, as many of the conference’s other NFL-ready players will likely follow their lead out the door rather than play in the winter or spring. Davis’ decision, in particular, is also evidence players have run out of patience waiting for the conference to figure out what the postponed season will look like, and that at least he has lost optimism in the Big Ten putting together a season that allows the Buckeyes to compete for a playoff berth.

More testing options are available

In his open letter to the community on Aug. 19, Warren wrote that “accurate and widely available rapid testing” could help mitigate some of the concerns associated with playing sports in a pandemic, but that “access to accurate tests is currently limited.” Since then, though, multiple developments in rapid COVID-19 testing have increased the access that should be available to the Big Ten.

The White House purchased 150 million rapid tests from Abbott Laboratories on Aug. 27, and has reportedly offered to distribute a portion of those tests to the Big Ten if it resumes fall sports. As of Tuesday, however, the Big Ten had not accepted that offer, according to Lettermen Row.

Even if the Big Ten doesn’t want to take tests from the government, there are other options that should also be available to the conference. The Pac-12 announced last week that it had reached an agreement with Quidel Corporation “to implement up to daily testing for COVID-19 with student-athletes across all of its campuses for all close-contact sports.” The Big 12 announced a similar arrangement on Friday with Virtual Care for Families that “will utilize Quidel Rapid Antigen tests which allow for 15-minute results and batch testing capabilities.”

Given that the Big Ten made the most revenue of any conference last season, the conference certainly should have the resources to put together a similar testing program for its 14 schools. As of now, though, it appears it could be up to the schools to do that on their own, as Sam McKewon of the Omaha World-Herald reported Thursday that Nebraska has arranged its own rapid testing program through a Quidel partner.

COVID-19 is still a real threat

Amid all the hand-wringing over the Big Ten being unable to play this fall while other conferences are, this is the biggest thing that probably isn’t being talked about enough: COVID-19 is still dangerous. More than 190,000 Americans have died from the pandemic. While none of those deaths have been directly linked to football being played, there are still many unknowns about the long-term effects of the virus, and even in the conferences that are playing right now, there have already been interruptions due to outbreaks within teams.

Nine games have already been postponed this season for reasons related to COVID-19 – not including games in conferences who postponed their entire seasons – while football team workouts are currently on pause at multiple Big Ten schools, including Wisconsin and Maryland. No matter when the Big Ten starts a football season, it is still going to have to have contingency plans in place for rescheduling games if teams are forced to put their seasons on hold due to increases in positive tests.

There’s more reason to believe now than there was a month ago that it will be realistic for full football seasons to be played, but teams are still going to have to deal with the looming threat of losing players – potentially even entire position groups, like last weekend when Texas State had to play with no tight ends – due to positive COVID-19 tests and contract tracing/quarantining policies. And the Big Ten still has to do what it decided it wouldn’t do a month ago: Accept the risk that football games could lead to COVID-19 spread, however big or small it might be, while trusting it has the policies in place to limit those risks effectively enough that it shouldn’t deprive its football teams the opportunity to play.

Yahoo Sports’ Pete Thamel reported Friday that while the Big Ten’s Return to Competition Task Force “is preparing a presentation to outline a safe way to return to play in the upcoming days,” there won’t be a vote “if the medical standards aren’t where they need to be – tests, contract tracing and myocarditis.”

University presidents will still decide if/when the season gets played

Amid all that has changed, one thing has remained exactly the same: The Big Ten’s council of presidents and chancellors still has the final say on if and when the conference will play football this season.

While coaches and athletic directors have been part of the committees that have put together the return to play plans that those presidents and chancellors will ultimately vote on, the approval of any plan will require at least five presidents who voted to postpone the season last month now voting in favor of returning to play.

It’s safe to assume that Ohio State, Nebraska and Iowa will all be voting in favor of playing in October if that’s the plan that’s ultimately voted on, and there is belief that there will be more presidential support for playing a season now than there was a month ago. But there are also still some Big Ten presidents who remain firmly opposed to playing this fall, including Rutgers’ Jonathan Holloway, who told NJ.com’s Steve Politi that he still believes the Big Ten should wait until spring semester due to the risks of COVID-19.

“If I’m wrong because I was erring on the side of safety, I don’t have a problem with that,” Holloway told NJ.com. “I don’t think I’m wrong, though. I just don’t think it. And if I had to put money down, we’re going to see some radical changes within a month -- no later than October. I’m really worried about what we’re heading toward, on just college campuses in general, not just sports. It’s deeply concerning.”

While the initial vote went 11-3 in favor of postponing the season, the next vote seems far more likely to come down to the wire, with eight votes needed to approve playing a season (while it has been reported that nine votes are needed, the Big Ten said in its initial response to the Nebraska players’ lawsuit that only a majority vote was needed to postpone the season). If any president is still on the fence about how to vote whenever that next vote comes, it’s possible that vote could swing whether or not the Big Ten plays this fall.