Ohio State adds another top-100 safety as Simeon Caldwell commits to the Buckeyes.

In the current era of college football, "spread" offenses often steal the starring role by gaining big attention for scoring in bunches and setting yardage records. The fascination among fans often trickles down in this direction, looking to identify the subtle differences between the "Air Raid," "Run and Shoot," and "Spread to run" systems favored by coaches in all corners. Many such schemes have found their way into NFL playbooks, and made coaches that once ran "gimmick" offenses into some of the hottest names in the game. Yet, in this day and age, it's almost considered barbaric to run a "pro-style" offense at the collegiate level.

The dirty little secret, however, is that all the spread systems that get publicity share a great deal of DNA with their pro-style brethren, and nearly every playbook in this day and age can be traced back to the "One-Back" offense of Dennis Erickson. Although his most successful stint came while at the University of Miami, a run often publicly credited to his predecessor, Erickson is considered a legend in coaching circles. He is often credited as the godfather of the grounding philosophy for virtually every NFL offense in the past twenty years.

While new Penn State coach James Franklin spent a year coaching at Washington State under one-back aficionado Mike Price, Franklin is often considered to be a pupil of former Maryland coach Ralph Friedgen, due to the eight seasons spent on his offensive staff. But Friedgen's time spent as an NFL offensive coordinator meant that Franklin was not only exposed to these philosophies early, but often.

Erickson has stated that his one-back offense is built first and foremost upon the ability to run the inside zone running play. The desire to run between the tackles was actually what initially prompted the move of the traditional fullback out of the backfield and replacing him with a third wide receiver. Moving a man out of the backfield removed an additional blocker, but it also meant that the defense had to adjust their alignment to cover that extra receiver.

By forcing defenses to declare their intentions to either cover the extra receiver or leave their man in place to defend against the run, offenses can easily decide at the line what play to run at the line. Erickson's teams often broke the huddle with two separate plays, and declared which one to run it through a code word or signal before the snap.

This discovery gave rise to the modern style of the offense (most commonly associated with successful pro coaches such as Bill Belichick and Sean Payton) looking to identify or create mismatches with existing personnel. By mixing and matching personnel combinations and alignments, quarterbacks can get a very easy read before the ball is snapped.

Perhaps no two players have taken advantage of this concept more than Rob Gronkowski and Jimmy Graham. With incredible combinations of size, speed, and hands, these two will line up anywhere from a traditional tight end alignment, to split out near the sideline, in the slot, and even in the backfield, all in an effort to create a mismatch with a smaller or slower defender.

While at Vanderbilt, Franklin and offensive coordinator John Donovan maximized the talent of star wideout Jordan Matthews, who finished his career as a Commodore with 262 receptions for 3,759 yards and 24 touchdowns, by following the same philosophy.

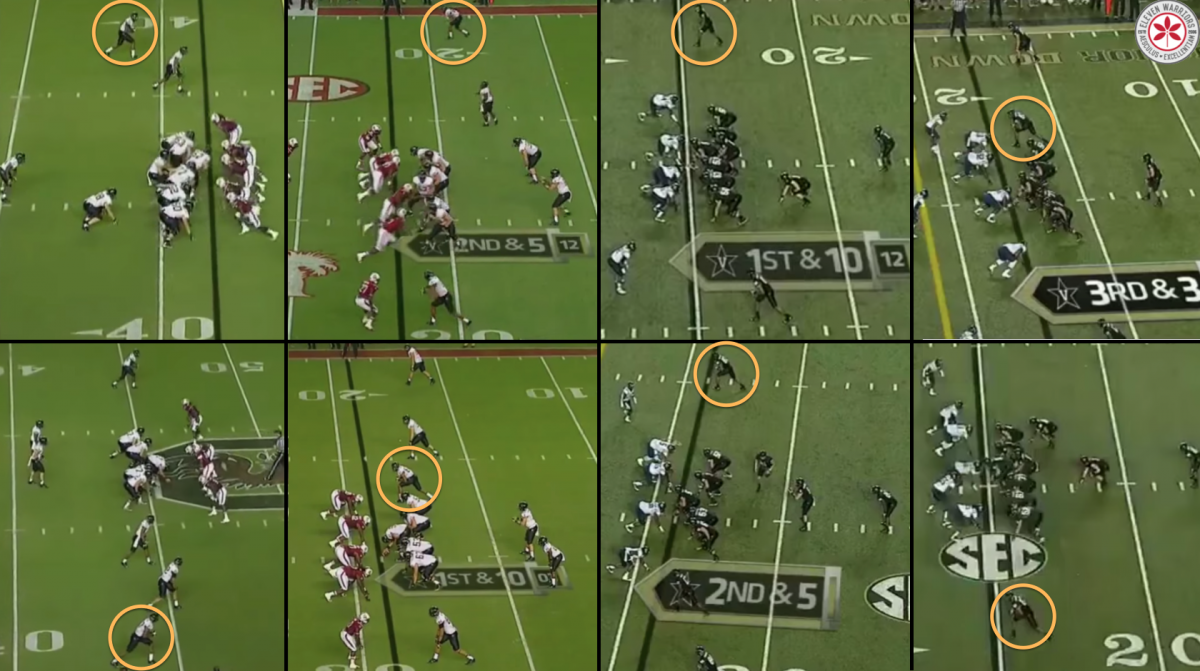

As seen above, Matthews lined up all over the field, split anywhere from a short slot just off the tackle all the way to the sideline. Note not only where he lines up though, but where his teammates are as well. Sometimes he was the sole receiver to one side, sometimes he was one of three, and lining up in any one of the spots. Sometimes the Commodores would motion a man towards him before the snap, sometimes a man away. Sometimes he was the one in motion.

Small tweaks to alignment wreaks havoc on a defense, forcing them to adjust and communicate on the fly. Sure, defenses could simply put their best defensive back on Matthews no matter where he lined up, but that would've meant that the other ten defenders must then adjust their responsibilities accordingly. Then again, if he lines up inside, who wants to cover him with a linebacker? The defense is put in a no-win situation, and must hope that the offense has strung themselves too thin by moving too many pieces on their end.

Although they won't have the chance to do the same with departed All-American Penn State receiver Allen Robinson, the new staff in Happy Valley still have plenty of tools at their disposal.

The 6'7" Jesse James and 6'4" Adam Breneman, a recruit highly desired by Urban Meyer, offer Franklin and Donovan more mismatch possibilities. While both are listed as Tight Ends, the two often lined up on the outside and in the slot in an effort to create opportunities for Robinson, but also for themselves.

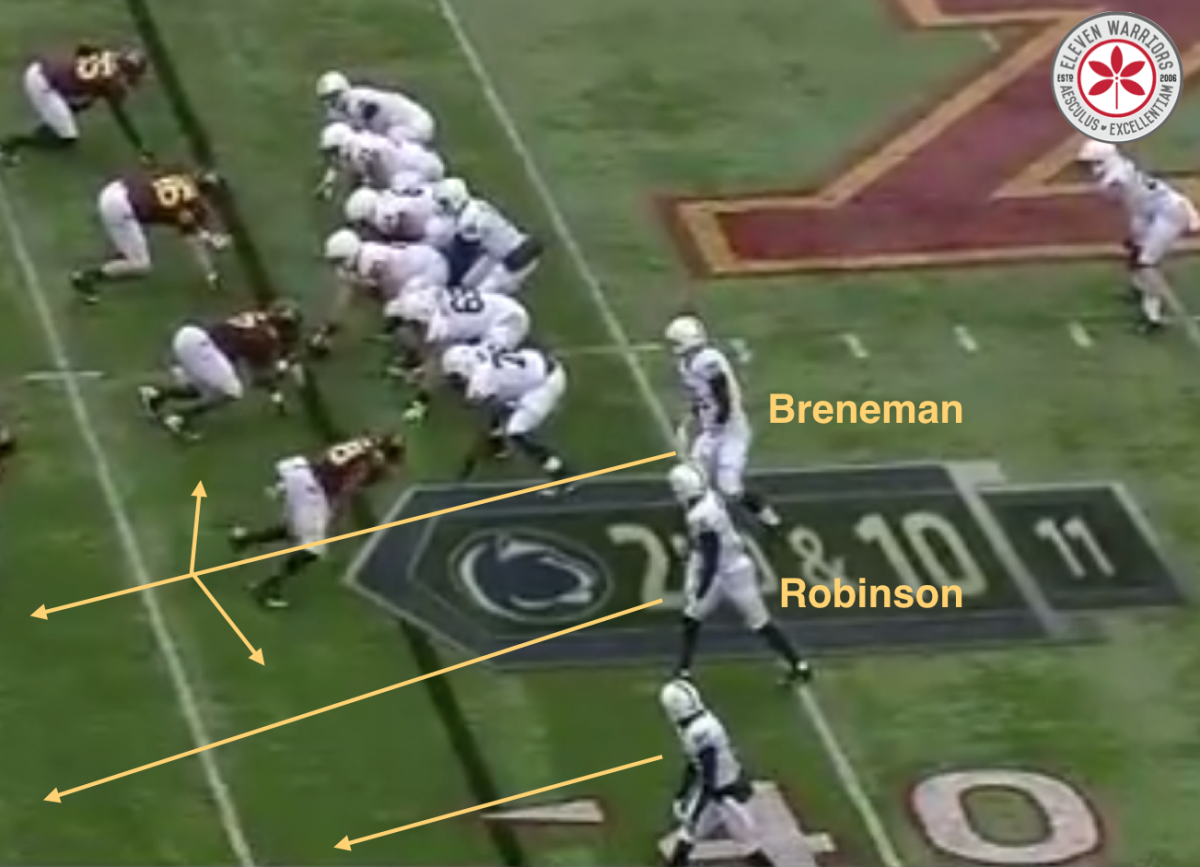

As we can see in this example against Minnesota, Breneman initially lines up as a wing on the outside of James before going in motion:

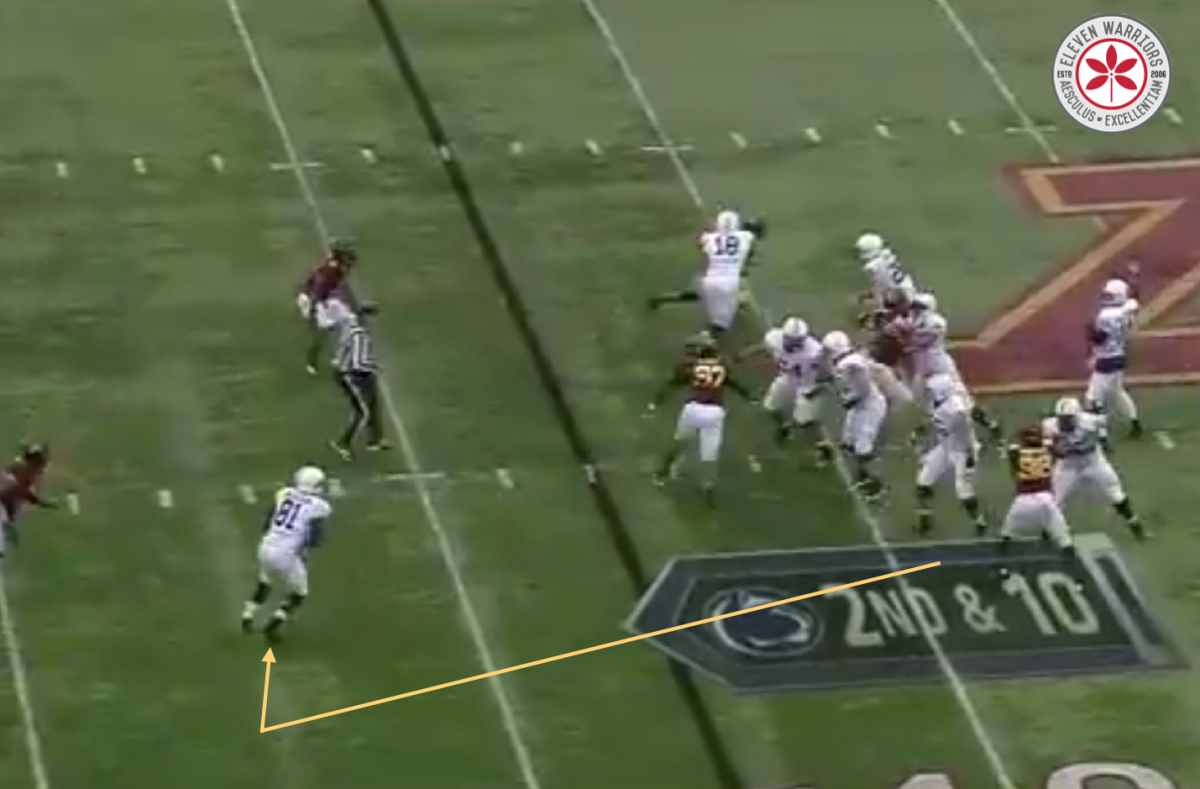

Now lined up as the third receiver inside and next to Robinson, he has become the responsibility of the third defender inside, who happens to be the middle linebacker (just out of the frame):

While middle linebackers are usually good athletes, they often aren't as athletic as Breneman, something everyone on that field knew. As such, the linebacker is very scared of getting beat deep, especially knowing that the outside receivers will be taking the attention of the safeties behind him. Breneman appears to be running an option route here, meaning that he'll simply cut away from his defender, no matter how he's covered, in an attempt to catch a quick pass underneath.

With the cushion given him, Breneman can simply stop and turn back to the QB for an easy five yard gain:

What initially appeared as an even formation with two receivers to either side became a three man route-combo with a major mismatch on one. James, the lone eligible receiver to his side, stays in to block, meaning the defensive backs to that side had nothing to do but sit and watch.

As mentioned earlier though, the offense must be able to execute in order to take advantage of these mismatches. Luckily for Franklin, his biggest weapon is also his most important, sophomore quarterback Christian Hackenberg.

After being named the starter in Bill O'Brien's offense, Hackenberg gained earned Big Ten Freshman of the year honors after throwing for 2,955 yards and 20 touchdowns. While many of those yards came from connections with Robinson, Hackenberg managed to hook up with his star tight ends on 40 occasions last fall.

The task will fall upon Franklin and Donovan to find the right balance between formations and personnel when looking to create mismatches in the passing game. But this isn't a new challenge for coaches of the one-back offense.

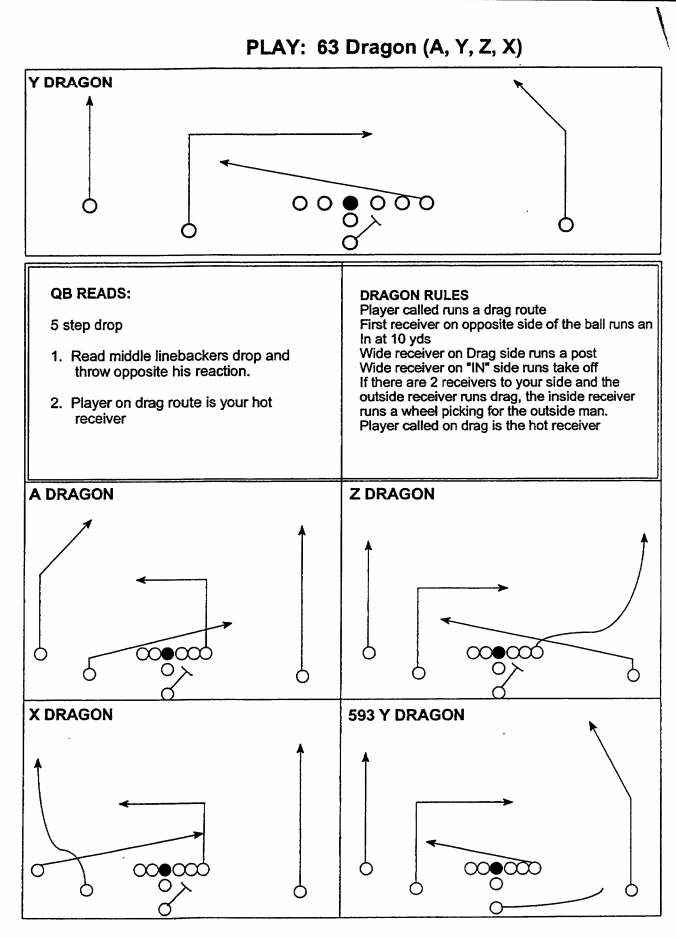

One of Franklin's former bosses, Mike Price, helped developed the original one-back system during his time as Erickson's offensive coordinator for Washington State in the late 1980s. A sample of his playbook from 2002 shows the underlying philosophy in how he (and his assistants like Franklin) taught the system to players:

This fairly simple concept calls for two deep vertical routes on the outside with a high-low combination over the middle. While Price laid out the way for this route combo to be run five different ways, the read for his quarterback was the same no matter what, "Read middle linebacker's drop and throw opposite his reaction." If the middle linebacker covers the deep route over the middle, then the QB throws underneath, or vice versa.

In an effort to simplify things for an offense, coaches have taken to teaching concepts more than individual plays. The line blocks the same way no matter which version of a play is called, and the quarterback has the same reads. The only difference here is that the receivers know they're running the drag route underneath if their position (A, X, Y, or Z) is called. Once players understand and become comfortable running the different pieces of a single concept, it becomes easy to run it from different formations.

In Franklin's first appearance as Penn State head coach, the Blue & White Spring game, the Nittany Lion offense featured a number of concepts and formations, showcasing everything from the "Wildcat" to a deep, vertical passing game. While some fans get scared of showing too much during such an exhibition, Franklin doesn't seem to mind, noting in an interview before the game, “I'm not one of these paranoid college football coaches. They have three years of really good film on us (from Vanderbilt). It's not like we're hiding a whole lot."

At a recent coaching clinic, he even joked about there being no 'special sauce' for success, and while the line was intended to be a motivational ploy to get his players to outwork their opponents, it can also be applied to his offensive strategies.

James Franklin's Penn State offense isn't going to do something you've never seen before, but instead will do everything in their power to identify and exploit the weaknesses of their opponents. With a great recruiting class already being assembled to give the Nittany Lions even more options down the road, it's easy to understand why he believes in this strategy.