About two months before I was set to graduate from Ohio State, I got a phone call from a friend telling me that our friend Tyson Gentry, a walk-on punter/receiver, had suffered a neck injury at football practice and was in the hospital. Initially, I thought it was a bad joke – a year and a half earlier, one of Ty’s best friends had collapsed and died on the practice field at Bowling Green due to complications with sickle cell disease. It felt especially cruel and unjust that the same thing was happening again, and at first I refused to believe it was true.

Not really knowing what to do, I called around to other friends to see if anyone had heard something — anything — positive. None of that news came. For a few weeks, the best news we had to hang on to was that Ty was 1) alive and 2) stabilized.

As is the custom of young twenty-somethings, I quickly went about focusing on myself and preparing to graduate from OSU. One night after a few hours at the bar, someone asked me about how Tyson was doing. I didn’t really know, and went home early that morning wracked with the guilt of not knowing.

When I got home from the bar I wrote Ty a letter, addressed it to him at the hospital, and dropped it in the mail. I wouldn’t have known about it if not for the fact that I had written a draft on my computer before transcribing it by hand, and the draft was still open on my computer the next morning. A week later I got a call from Ty, we caught up, and he invited me to visit him at Dodd Hall, the OSU Medical Center’s rehabilitation hospital at the southern end of the medical campus.

On a bright, clear Mid-May Sunday, I walked the mile and a half from my house at Lane and Waldeck down to Dodd Hall. The thing about rehabilitation hospitals that I didn’t realize at the time is that they can be incredibly jarring the first time you walk the hall of one. The hospital’s corridors – not exactly bright and cheerful places to begin with – feel quite claustrophobic, filled with extra wheelchairs and the sounds of rehabbing patients. In rehab hospitals, patients groan – loudly. Depending on the number of open room doors, little to no light from outside reaches the hallways. The walk from the elevator to a patient’s room is, to be generous, quite grim.

Inside Tyson’s room, though, it felt like a different world: Tyson’s parents Bob and Gloria and his sisters Natalie and Ashley welcomed me into his room. I had graduated from high school with Ashley four years earlier, and she was graduating from Capital University later that day. We talked about graduation and post-college plans while Tyson was being taken care of in the bathroom. Two of Bob and Gloria’s friends from Maryland were in to visit, and they told me about Maryland, where I was headed for post-graduate study in the fall.

When Ty emerged from the bathroom with the help of an aide, there was little left to be scared of – he looked a bit frail, and needed a shave, but otherwise looked to be himself. The state of his current urinary tract infection came up – a common issue with paralysis patients – followed by a quick apology from the aide for bringing up a possibly embarrassing topic.

The response from Ty’s father was quick and to the point: “it’s okay - we’re all family here.”

In the almost nine years since his injury, Tyson has served as a captain at the 2009 Fiesta Bowl, graduated from OSU with a degree in speech and hearing science, moved to Florida, earned a Master’s Degree in Rehabilitation Counseling, and gotten married to a great woman that he met after his accident. (Don’t tell my daughter, but the first dance at his wedding was without question, the sweetest I’ve seen in my entire life.)

He’s remained unrelentingly encouraging, thoughtful, and optimistic. I haven’t heard him complain about anything, once, during our visits. He’s made a number of paintings, all of which are far more detailed and beautiful than anything I have ever managed to make with my two fully-functional hands.

Last week, Tyson launched the New Perspective Foundation, a non-profit focused on assisting the families of those affected by spinal cord injuries in Ohio and Florida. The financial costs incurred by families of injury victims can be huge – short-notice airfare, lodging, gas, food, etc. – and New Perspective’s pilot program, Closing The Distance, is designed to help defray those costs and enable families and friends to spend time with their loved ones quickly following injury.

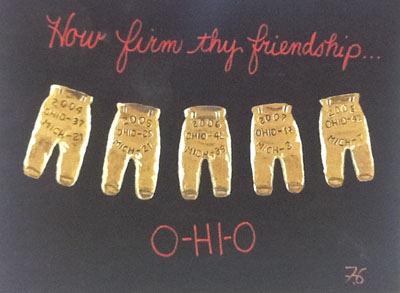

When I was at OSU, we were inundated with reminders to 1) Do Something Great and 2) Pay It Forward. Tyson’s doing both of those things – and to get the foundation off the ground and running, he is selling 200 limited edition individually signed and numbered prints of a painting depicting his five (5) pairs of Gold Pants for $150. After those signed prints are gone, standard prints will be available for $75. Information about the prints and donations to the foundation can be found here. Donations are tax-deductible.

I feel the need to note here that it was difficult for me to make my initial trip in 2006 to see Tyson, because, well, going to a rehabilitation hospital is not a thing that most people wake up and want to do. The thought of seeing a good friend in a physically damaged state terrified me. Once I made the visit those fears seemed silly and selfish in retrospect. But they were real prior to stepping into Ty’s room – and I was someone who merely walked a mile and a half to visit a friend in the hospital. The barriers for my visit were minimal, yet were nearly enough to stop me from going.

I offer my experience with Tyson’s injury not as canonical evidence, but as one perspective of the impact that spinal injuries have on entire networks of people. Tyson and his family are some of the warmest and most caring people I’ve ever met, and they have carried on with a grace and dignity that I imagine will be imbued in the work that New Perspective does. Not everyone affected by spinal cord injuries has the support network that Tyson had at the time of his injury, but it doesn’t have to be that way; any and all visitors are welcomed in times of great need. New Perspective is making sure that happens.

The final run of my high school track career was a 300-meter hurdle race in the sectional finals of my senior year. My start was fine and the back straight passed without note. Approaching the last hurdle before the curve, I over-strode slightly and got twisted up. In a race with little breathing room, that twist did me in, and I knew it.

I shot a furtive glance to the side and saw my training partner –Tyson. He was standing at the bend, standing where we always stood, along with all of my teammates. It seemed to me that in that moment he sensed my panic and knew that I knew that my running career was done after that hurdle. While I was in the air, Ty leaned into the fence and calmly said to me “Go”. Amid the din of the crowd, that’s all I heard – Go.

Now, Tyson’s going to work telling others the same thing he told me so many years ago – Go.