Roughly 50 miles north of the Wyoming border sits Bozeman, Montana, a town known mostly for its airport.

Each year, nearly half a million travelers make their way through its terminal, coming from places like Denver, Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, or Seattle and descending on the town of roughly 37,000 residents before heading off for an adventure in one of the nearby national parks.

Within football circles, though, the otherwise small town is known for an aerial legacy that can be traced to the campus of Montana State University, 10 miles southeast of the BZN tarmac. While the Bobcats began competing in 1946 and only sport a winning percentage of .505 since, MSU's contribution to the game is difficult to truly measure.

In particular, the period from 1963-1967 in which Jim Sweeney was head coach created a ripple effect across the sport that is still being felt today. While Sweeney is remembered locally for leading the team to three conference titles in five seasons before leaving for Washington State in 1968, it was two of his players that would help shape the sport as we know it: a quarterback named Dennis Erickson and an offensive tackle from Toledo, Ohio named Joe Tiller.

Tiller would eventually follow Sweeney west, joining the Cougars' staff in 1971 and forming a bond with a fellow assistant named Jack Elway, who would eventually leave to take the head coaching job at Cal State Northridge in 1976. While in southern California, Elway famously scouted all the local high schools to find the perfect place for his talented son to flourish, eventually settling on Granada Hills High School, which was led at the time by a man named Jack Neumeier.

As was detailed in-depth by Tim Layden in his excellent book, Blood, Sweat and Chalk, Neumeier was an old-school, defensive-minded coach that had grown tired of falling short of his goal of winning a Los Angeles city title before stumbling upon a copy of Glenn "Tiger" Ellison's famous book, Run and Shoot: Offense of the Future and decided to implement many of its principles in 1970. By the time the elder Elway began shopping for schools six years later, the Highlanders' passing attack with three or four wide receivers had already made waves in the area.

Of course, with a trigger man as talented as Elway under center, Granada Hills became nearly unstoppable, throwing for a then unheard of 5,711 yards and 49 touchdowns in three seasons despite the quarterback's knee injury which cost him five games his senior year. As Neumeier told the Los Angeles Times in 1990:

"Basically, my offense spreads the defense across the field. A lot of teams will spread the defense the depth of the field, like the Raiders for instance, but my idea is to spread them sideline-to-sideline so you never get two defensive backs to cover one receiver. And when you catch the defense in a one-on-one, the receiver should go to an open spot and should get there before the defender because he knows where he's going."

As both Elways headed north in 1979, John to play quarterback at Stanford while Jack took over the nearby program at San Jose State, many of Neumeier's ideas went with them. When the elder Elway needed an offensive coordinator that fall, he tapped into his network and found one of Sweeney's former proteges, Erickson, ready for the job.

From there, Erickson ran with the ideas originally put forth by Neumeier, formalizing a playbook that would shape the game for decades to come by removing a player from the backfield and splitting them out wide, forcing the defense to respond in kind. Not only did this make it easier to throw the ball, as a linebacker was often forced to cover the additional receiver in wide open grass, but it became easier to run the ball as well with fewer bodies clogging up the box.

After three seasons in San Jose, Erickson was named the head coach at the University of Idaho despite only being 34 years old, immediately taking a three-win team from the year before to an 8-3 record and an appearance in the D-1AA playoffs in 1982. After four seasons with the Vandals, Erickson got the call up to D-1A, taking over at Wyoming in 1986. The following season, Erickson would move yet again, this time to Washington State, where he’d create a pattern that would have a major impact.

A fellow Montana State alum, Tiller, had remained in contact with his Sweeney and Elway throughout the years and would join the Wyoming staff after Erickson left, but quickly decided to keep the offense in place due to its success. As Tiller told Layden in Blood, Sweat and Chalk,

“Dennis came in and threw the ball all over the place, and people loved it.” Erickson left for Washington State after just one season, but his offense he had brought stayed in place; when Tiller became head coach at Wyoming in ’91, he did nothing to change it. “I had no choice; they loved what Dennis had done,” Tiller says. “People have asked me for years how I learned this offense. I tell them, ‘Dennis left his playbook at Wyoming.’ And that’s absolutely the truth.”

Erickson would do the same at Washington State when he left to lead the Miami Hurricanes to a pair of national titles thanks, in-part, to his offense that had become known as the One-Back Spread. His successor in Pullman, Mike Price, would evolve the system throughout the nineties, turning into the 4-wide machine that would take the Cougars to the 1998 Rose Bowl and make Ryan Leaf a household name.

Tiller, meanwhile, would find success of his own in Laramie, allowing him to return home to the Midwest in 1997 as the new head coach at Purdue. Of course, Erickson's playbook came with him, and Big Ten record books would never look the same.

The Boilermakers had the perfect quarterback for the system in Drew Brees, an undersized Texan with good athleticism and a quick release. Like Price, Tiller's evolution of the system focused far more on the passing game, as Brees attempted a conference record 1,671 passes throughout his storied career.

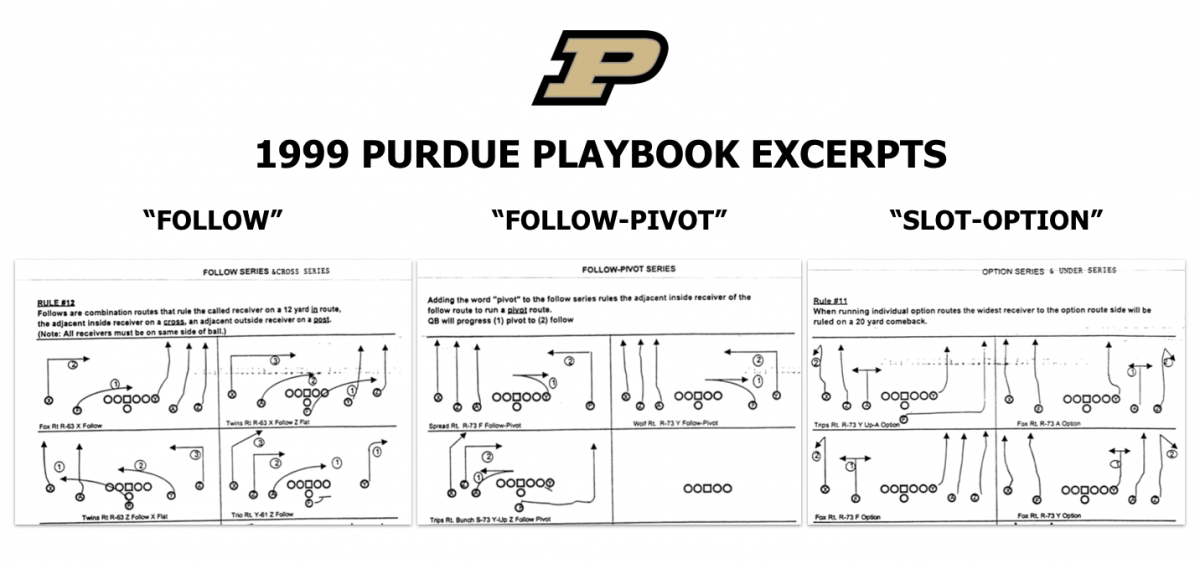

Tiller and his top lieutenants, offensive coordinator Jim Chaney and quarterback coach Greg Olson, broke their passing game, then known as Basketball on Grass for the way the ball moved so quickly around the field, into three segments:

- 90 series: Purdue's quick passing game that spread the ball out in a hurry to receivers often running slants, hitches, outs, or fades

- 70 series: Route concepts designed to attack vertically downfield, often with max protection in the pocket

- 60 series: Intermediate crossing receivers usually running routes at a depth of 10-15 yards

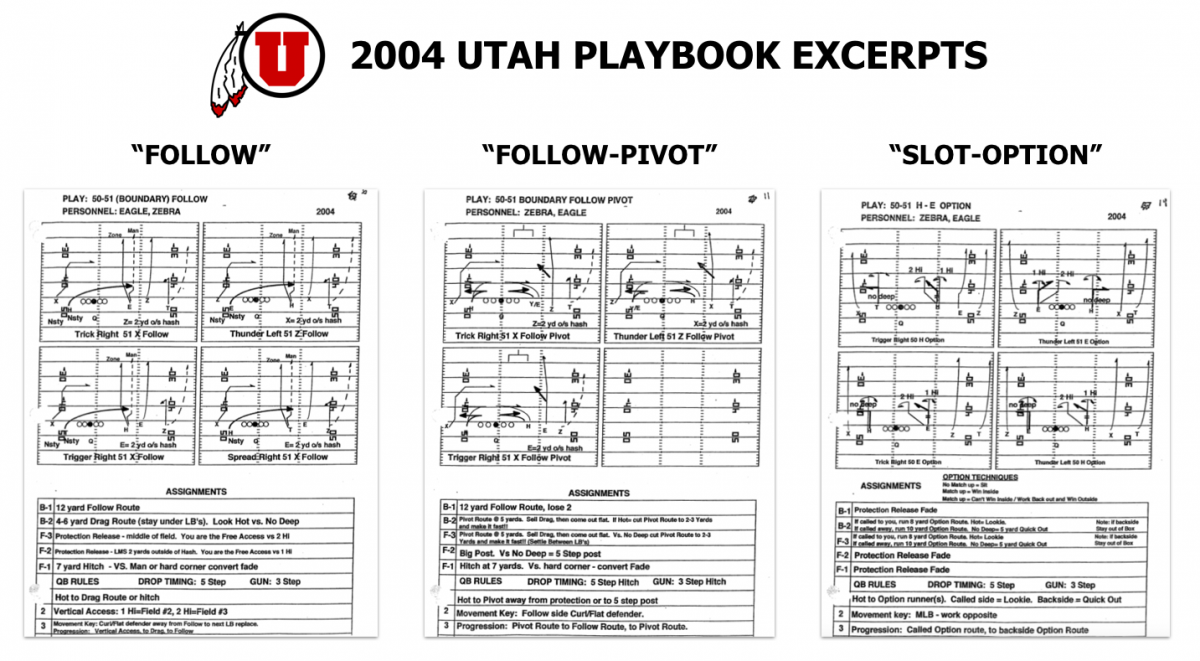

This final series featured a set of route combinations that would separate Brees and the Boilers from other passing games, most notably the Follow concept. This basic idea cleared out one side of the field with deep routes while two receivers ran crossing routes from the other side. The name, of course, comes from the second crosser, who effectively follows the path of the first, forcing a defender in zone coverage to choose which to cover and often leaving one open.

When defenses began to overplay the crossers, often by simply applying man-coverage, Purdue had the perfect counter in the Follow-Pivot. This variation saw the first receiver begin his crossing route before planting his foot in the ground and breaking outside, creating space between him and the nearest defender.

Just as Brees' record-setting career came to close following the 2000 season, a young assistant at Notre Dame began noticing what was happening at places like Washington State, Purdue, and Louisville, led at that time by a pair of Erickson's former assistants, John L. Smith and Scott Linehan. According to that Irish assistant, the talent and complexity of defenses they were facing had grown so much that it had become difficult to move the ball from traditional I-formation sets, leading to his interest in the ways these teams were doing so with relative ease.

Of course, that young coach was none other than Urban Meyer, who would take his first head-coaching job at Bowling Green in advance of the 2001 season. As he told Eleven Warriors in 2012, he had spent a great deal of time studying these teams in person by then, going directly to the source to quench his thirst for knowledge:

"In 1999, Dan Mullen was my GA at Notre Dame. John L. Smith was the coach at Louisville and Scott Linehan was the offensive coordinator. I started watching them on film and said I want to go study them. He said sure go ahead. We ended up staying four days and had to go buy a toothbrush. I was so enamored with the style of play. That was spread the field and be extremely aggressive. The biggest issue was how to handle pressures. The tighter the formation, the more pressures. It's really a numbers game. It was a different philosophy I had never really…after that, both Dan and I really attacked it. I started getting phone calls about being a head coach and thought about what I would do offensively."

Meyer and Mullen also spent time with Randy Walker and Kevin Wilson of Northwestern, along with Rich Rodriguez (then the OC at Clemson), to understand how to incorporate their shotgun running game into the One-Back Spread principles he'd picked up from the Louisville and Purdue staffs. Thanks in large part to his adapted version of the system, Meyer's offenses excelled, propelling him on to Utah, Florida, and eventually to where he is today at Ohio State.

Over time, defenses caught up to many of the tactics brought forth by Erickson, Tiller, Price, and their many proteges, leading to a dilution of the original system seen 20 years ago. Even Meyer has looked elsewhere to freshen up his own since arriving in Columbus, leaning on Tom Herman to add new thinking to his playbook in 2012 and bringing Ryan Day onboard last fall in hopes of incorporating the thinking of his mentor, Chip Kelly.

But throughout his five seasons in charge of the Buckeyes, those familiar with the One-Back Spread can still see pieces of it in Meyer's passing game. Even though many believe his quarterbacks were recruited more for their legs than their arms, another athletic Texan that made his way north ended up using many of the same plays to break a number of Brees' Big Ten records.

Though it's fallen a bit out of favor in recent years due to the rising commonality of pattern-matching coverage, the Follow concept remains largely unchanged from the one found in Tiller's playbook 20 years ago. Conversely, though, Meyer evolved the Follow-Pivot concept to feature two pivot routes, creating a triangle read over the middle with the addition of the crossing route, which has still proven difficult to defend all these years later.

Similarly, the slot-option concept featured not one, but two such routes up the seams, giving the QB an easy read of the middle linebacker. In 2016, when Curtis Samuel was the best Buckeye receiver and lined up primarily in the slot, this play was called countless times, allowing J.T. Barrett to rack up countless easy completions, just as Brees had.

Though Brees still holds the Big Ten career record for passing yards with 11,792, a total of over 2,300 more than Barrett, Brees also attempted 467 more passes over the course of his four years at Purdue. But despite throwing it less often, Barrett still managed to finish his collegiate career as the Big Ten's all-time leader in touchdown passes with 104 to Brees' 90 and actually ended with a career passing efficiency rating of 152.33, 20 points higher than the Boilermaker legend.

But many of the concepts engineered by the One-Back Spread originators didn't stay confined to the college and high school ranks, despite their relative simplicity. As Meyer became one of the sport's biggest names while at Florida, he famously built a relationship with Bill Belichick. As noted by Chris B. Brown, Meyer was likely the one who taught the philosophies and concepts to the legendary Patriots head coach as well as his assistants, Josh McDaniels and Bill O'Brien.

Once again, records would be shattered as the trio incorporated plays like Follow into their playbook, allowing Tom Brady to have an easy read with Randy Moss running a vertical stretch on one side of the field while Wes Welker streaked across the other.

Over time, many of the formations and route concepts developed by Erickson and co. have become so common that they've lost the unique identity that set them apart. The one-back running game, powered heavily mainly by zone-blocking, is the base play installed on the first day of practice at nearly every program from high school to pro.

But so many of the game's top offensive minds owe at least a little something to the guys that worked or played at Montana State, Granada Hills, and Wyoming. Even though much of their work was done in places where few were watching, the payoff for that effort can be seen every Friday, Saturday, or Sunday in the fall.